The Myth of Tantalus

Story by: Greek Mythology

Source: Ancient Greek Legends

The Myth of Tantalus

In the golden age when gods still walked among mortals, there lived a man named Tantalus, king of Sipylus in Anatolia. Tantalus was no ordinary mortal—he was the son of Zeus himself and the nymph Plouto, whose name means “abundance.” This divine parentage granted him privileges few humans could imagine. He was welcomed at the feasts of the gods on Mount Olympus, where he dined on ambrosia and nectar, the food and drink of immortals. The gods shared their wisdom with him, trusted him with divine secrets, and treated him almost as an equal.

Yet as is often the case with those granted exceptional favor, Tantalus began to grow proud. The line between confidence and arrogance blurred in his mind until he could no longer distinguish between being honored by the gods and being their peer. This confusion would lead to a series of transgressions, each more shocking than the last, and ultimately to a punishment that would echo through eternity.

Tantalus’s first crime was born of loose lips and reckless pride. Having been privy to the gods’ private counsels, he returned to the mortal world and shared divine secrets with his fellow humans—sacred knowledge never meant for mortal ears.

“The gods are not so different from us,” he would boast at his palace banquets, wine loosening his tongue. “They have their squabbles and jealousies, their petty concerns—just magnified by their power. Let me tell you what Zeus confided in me about Hera’s latest rage…”

And so he would reveal the hidden workings of Olympus, diminishing the mystique of the gods and betraying the trust they had placed in him.

Word of these indiscretions reached Olympus, as all things eventually do, but the gods—particularly Zeus, remembering that Tantalus was his son—chose to overlook this breach of etiquette. After all, mortals had short lives and shorter memories. What lasting harm could come from a few divine secrets being whispered in mortal ears?

But Tantalus, emboldened by this apparent indifference to his first transgression, soon committed a second, more serious offense. During one of his visits to Olympus, while the gods were distracted with their revelry, Tantalus stole portions of ambrosia and nectar—the divine food and drink that granted the gods their immortality—and smuggled them back to earth to share with his mortal friends.

“Taste this,” he would say, offering the golden substances to wide-eyed courtiers. “This is what gives the gods their power, their eternal youth. Why should they keep such treasures to themselves?”

This theft could not be so easily overlooked. Zeus summoned Tantalus to Olympus, his face dark with disappointment and anger.

“My son,” Zeus said, his voice rumbling like distant thunder, “twice now you have abused our trust. The secrets of the gods are not for mortal ears, and the food of immortality is not for mortal lips. Consider this your final warning. Your divine blood has earned you leniency, but my patience is not infinite.”

Tantalus bowed low, his face a perfect mask of contrition. “Forgive me, Father. I was overcome by the desire to share the wonders of Olympus with those less fortunate. It will not happen again.”

Zeus nodded, accepting the apology at face value. “See that it does not. The boundary between gods and mortals exists for a reason. Even my own children must respect it.”

But Tantalus had not truly learned his lesson. In fact, the warnings only served to fuel his growing resentment. Why should there be boundaries he could not cross? Was he not of divine blood? Did he not deserve the same privileges as the full gods? His heart grew bitter with these questions, and a terrible plan began to form in his mind—a plan to test the gods’ omniscience and, perhaps, to mock their pretensions of superiority.

Upon returning to his kingdom, Tantalus prepared to host a great banquet and invited the gods to dine at his palace. It was a rare honor for a mortal to host the Olympians, and the gods accepted, curious to see what delicacies their favored mortal would prepare for them.

What the gods did not know was that Tantalus had committed an act so horrific that it would forever change how they viewed humanity. In preparation for the feast, Tantalus had taken his own son, Pelops, a boy of extraordinary beauty and innocence, and slaughtered him like an animal. He then butchered the boy’s body, boiled some portions and roasted others, and prepared them as the main dish for the divine banquet.

“Let us see if the all-knowing gods can tell what meat they are eating,” Tantalus thought with perverse glee. “If they cannot recognize human flesh, how omniscient can they truly be? And if they do recognize it but eat it anyway, how are they morally superior to humans?”

When the gods arrived at the palace of Tantalus, they were greeted with all the pomp and ceremony befitting their divine status. The banquet hall was decorated with the finest tapestries, the tables laden with golden plates and jeweled goblets. Tantalus himself played the gracious host, welcoming each deity with honeyed words and flattering compliments.

But as the covered dishes were brought out and placed before the immortal guests, a strange hush fell over the gathering. Most of the gods immediately sensed that something was terribly wrong with the meal set before them. The smell was not quite right, the appearance not quite as it should be. Divine intuition warned them of the unspeakable nature of the “delicacy” their host had prepared.

Only Demeter, distracted by grief over her missing daughter Persephone, failed to notice the warning signs. In her distracted state, she absentmindedly took a bite of the meat—a small portion from Pelops’s shoulder—before she too realized the horrific truth of what was being served.

Zeus rose from his seat, his face terrible with rage, and hurled the plate to the floor. “What abomination is this?” he thundered, causing the very foundations of the palace to shake. “Have you fallen so far, Tantalus, that you would serve a father the flesh of his own son?”

The other gods stood as well, their faces reflecting shock, disgust, and growing anger. Tantalus, suddenly realizing the magnitude of his error, fell to his knees.

“It was only a test,” he stammered, all his earlier confidence evaporating in the face of divine wrath. “I merely wished to see if you could tell—”

“Silence!” Zeus commanded, and the very air seemed to compress with the power of his word. “You have crossed a boundary from which there is no return. You have violated not just our trust, but the most sacred laws of nature and kinship.”

The gods gathered the dismembered pieces of Pelops and, through their divine power, reassembled them in a great cauldron. They restored the boy to life, his body made whole again—with one exception. The small piece of shoulder that Demeter had consumed was replaced with a piece of ivory, crafted by the divine smith Hephaestus himself. This ivory shoulder would become a mark of divine favor, visible proof that Pelops had been touched by the gods themselves. In later years, it would grant him and his descendants special powers and a distinguished lineage.

But for Tantalus, there would be no restoration, no second chance. Zeus pronounced his judgment with the finality of fate itself:

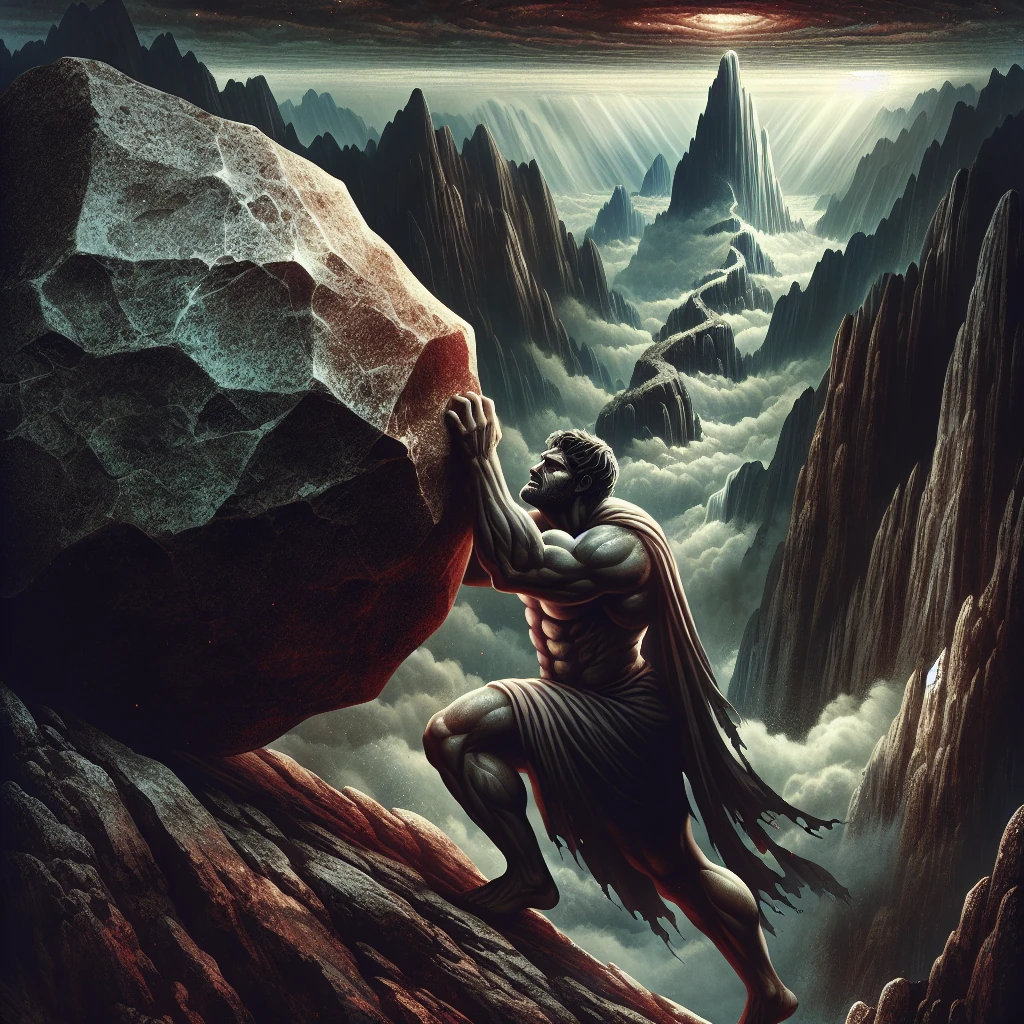

“For your crimes against the gods and against your own blood, you shall be cast into Tartarus, the deepest pit of the Underworld, where the most wicked souls receive eternal punishment. And your punishment shall fit your crime.”

Hermes, the messenger god who also guided souls to the Underworld, seized Tantalus and transported him instantly to Tartarus, where Hades, lord of the dead, was waiting to implement Zeus’s sentence.

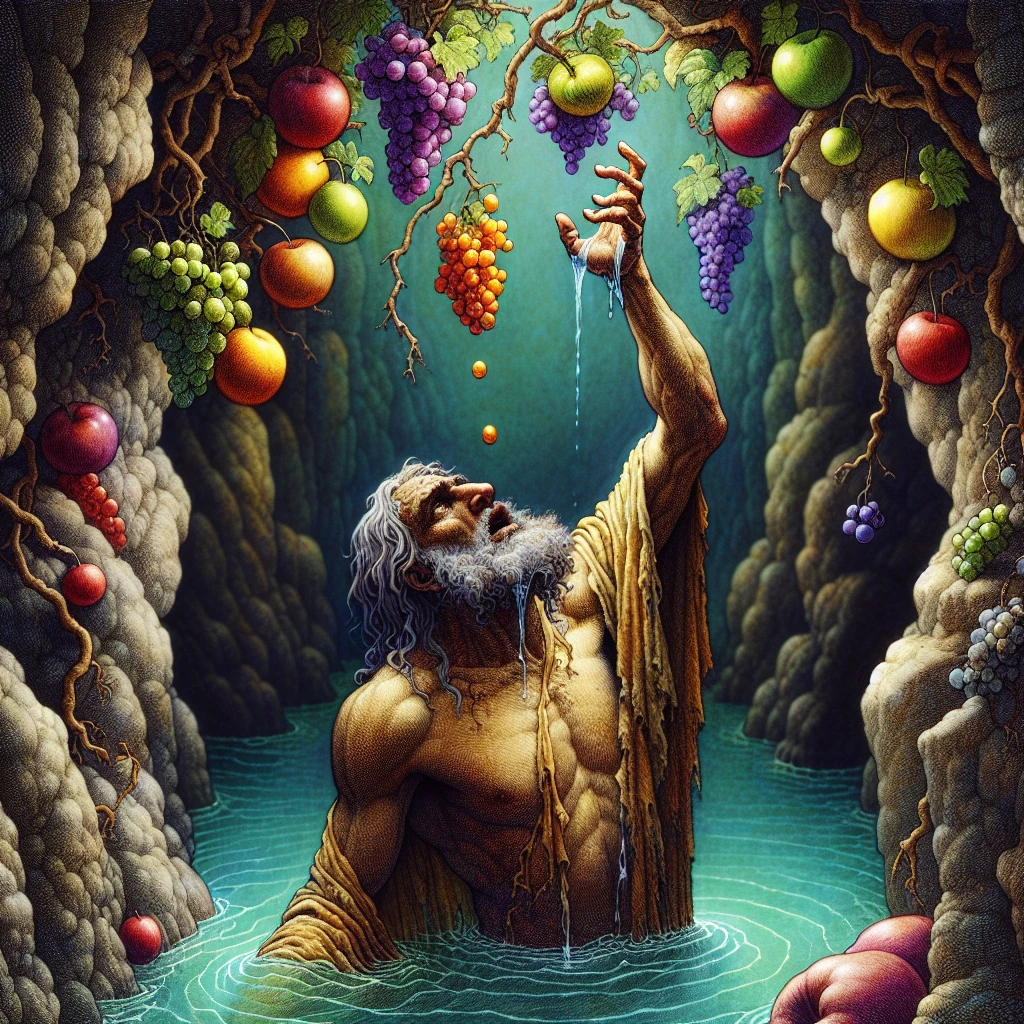

Tantalus was placed standing in a pool of fresh, clear water that reached to his chin. Above his head hung branches laden with ripe, succulent fruit—figs, apples, pears, and clusters of grapes, all appearing perfect and delicious. But whenever Tantalus bent to drink from the pool, the water receded away from his lips, leaving him unable to quench his burning thirst. And whenever he reached up to pluck a fruit from the branches, a sudden wind would lift them just beyond his grasp.

“As you offered food that should never be consumed,” pronounced Hades, “so shall you forever crave what you cannot consume. As you existed among abundance but corrupted it with your actions, so shall you be surrounded by abundance that you can never enjoy. Your name shall become synonymous with this torment—to tantalize, to show what is desirable but place it forever out of reach.”

And so began the eternal punishment of Tantalus, standing forever in his pool with fruit he could never eat dangling forever above him, suffering constant hunger and thirst in the midst of plenty—a fate so terrible that it gave our language the word “tantalize.”

But the consequences of Tantalus’s crimes extended beyond his own punishment. His entire bloodline—the House of Atreus—would be cursed with a legacy of violence, betrayal, and tragedy that would span generations. His daughter Niobe would lose all her children to divine arrows after boasting that she was superior to the goddess Leto. His grandson Atreus would serve his brother Thyestes a meal made from Thyestes’s own sons, eerily echoing Tantalus’s original crime. The great-grandchildren of Tantalus would include Agamemnon and Menelaus, central figures in the Trojan War, whose family drama of sacrifice, murder, and revenge would form the subject of many Greek tragedies.

The Greeks told the story of Tantalus as a warning about the dangers of hubris—the arrogant pride that leads mortals to believe they can equal or outwit the gods. But beyond that obvious moral, the myth explores more complex ideas about boundaries, trust, and the proper relationship between mortals and divine powers.

Tantalus was not punished simply for associating with the gods—indeed, he was initially welcomed into their company. His crime was abusing that privilege, failing to understand that being favored by the gods did not make him their equal. The gods could invite mortals to cross the boundary between realms temporarily, but that did not erase the boundary itself.

The myth also exposes the tension in Greek thought between divine justice and divine favoritism. Tantalus was initially protected from consequences by his divine parentage, receiving warnings where other mortals might have been punished immediately. Yet when he committed his final, unforgivable transgression, not even his status as Zeus’s son could save him. This suggests a moral universe where connections and privilege might delay justice but cannot ultimately prevent it.

Perhaps most disturbing is the way Tantalus weaponized the sacred bond between parent and child. In Greek culture, as in most societies, certain relationships were considered inviolable—particularly the duty of parents to protect their children. By slaughtering his son to make a point to the gods, Tantalus didn’t just commit murder; he perverted the natural order in a way that shocked even the Olympians, who were no strangers to violence.

For modern readers, the story of Tantalus may seem excessively gruesome, the punishment disproportionate to even such terrible crimes. But in the moral logic of Greek mythology, certain actions were so fundamentally wrong that they warranted eternal consequences. Tantalus didn’t just break rules; he violated the basic trust that makes civilization possible—trust between host and guest, between parent and child, between the favored mortal and the gods who elevated him.

As Tantalus stands forever in his pool, reaching for fruit he can never grasp and bending toward water he can never drink, he embodies the ultimate futility of seeking to rise above one’s proper place in the cosmos through deceit and cruelty. The abundance that surrounds him but remains forever out of reach symbolizes how his own actions transformed his privileged position into eternal deprivation.

And as we use the word “tantalize” in our everyday speech, we keep alive the memory of a king who had everything—divine parentage, the favor of the gods, a prosperous kingdom, and a beautiful son—yet lost it all because he could not be satisfied with these extraordinary blessings, but insisted on testing the boundaries that separated him from godhood itself.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus