The Myth of Pasiphaë

Story by: Ancient Greek Mythology

Source: Greek Mythology

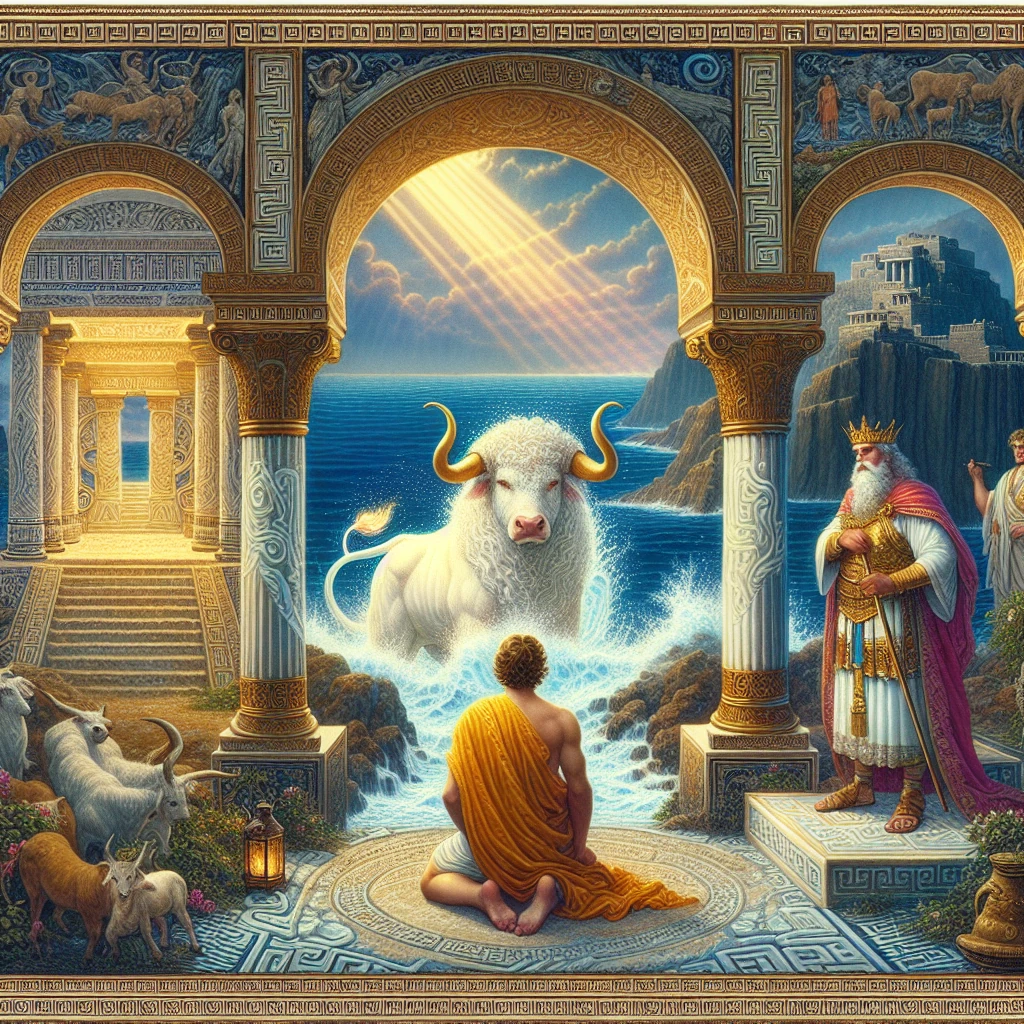

On the island of Crete, where the blue waters of the Mediterranean met shores of golden sand and the palace of Knossos rose like a jewel among the olive groves, there ruled a king whose ambition would bring both glory and terrible tragedy to his family. This was King Minos, and his wife was Pasiphaë, daughter of the sun god Helios, whose beauty was as radiant as her divine heritage suggested.

Pasiphaë was no ordinary queen. As the daughter of Helios, she possessed an otherworldly beauty that made her seem touched by sunlight even in the deepest shadows. Her hair gleamed like spun gold, her skin had the warm glow of amber, and her eyes held depths that seemed to reflect the infinite sky. She was wise in the ways of both mortals and immortals, and her counsel was valued throughout the palace of Knossos.

King Minos loved his divine wife deeply, and their marriage had been blessed with children, including the beautiful Ariadne and the strong young Androgeus. For many years, they ruled Crete in harmony, their kingdom becoming the greatest maritime power in the Mediterranean, with ships that carried Cretan goods and culture to every corner of the known world.

But Minos was not content merely to be a successful king. He had greater ambitions—he wanted to expand his power beyond the seas to become ruler of neighboring lands as well. To accomplish this, he needed divine support, and he knew that the gods looked favorably upon rulers who demonstrated their piety through proper sacrifices and rituals.

The opportunity came when Minos decided to claim dominion over the seas around Crete, a move that would require the blessing of Poseidon, god of the oceans. To win the sea god’s favor, Minos planned a magnificent sacrifice that would demonstrate his devotion and worthiness.

Standing on the cliffs overlooking the harbor, with all his court assembled behind him, Minos raised his arms to the sky and called out in a voice that carried across the waters:

“Great Poseidon, lord of the seas, I, Minos, king of Crete, call upon you to show your favor for my reign! Send me a bull from your sacred herds, white as sea foam and perfect in every way, and I will sacrifice it to your honor before all my people!”

The response was immediate and magnificent. The sea began to churn and foam, and from the waves emerged the most beautiful bull anyone had ever seen. It was pure white, without blemish or mark, with horns like polished ivory and eyes that seemed to hold the power of the ocean itself. The creature walked calmly onto the shore, its presence radiating a divine majesty that made everyone who saw it fall to their knees in awe.

“Behold!” Minos declared triumphantly. “Poseidon has answered! The god of the seas supports my reign and blesses my ambitions!”

But as Minos looked upon the magnificent bull, a terrible temptation overcame him. The creature was so beautiful, so perfect, that the idea of killing it seemed almost sacrilegious. Surely Poseidon would not mind if he substituted another bull for the sacrifice—one from his own herds that was almost as fine but not quite so extraordinary.

“I will keep this divine bull for my own,” Minos thought, “and breed it with my finest cows to create a herd worthy of a king who rules the seas. Poseidon will understand—after all, I am honoring the bull by preserving it rather than destroying it.”

So instead of sacrificing the sacred bull as he had promised, Minos substituted another animal from his own herds and kept the divine creature for himself, adding it to the royal stables and treating it as a prized possession rather than a sacred trust.

For a time, it seemed that Minos had been clever rather than foolish. The bull thrived in the royal pastures, and his naval campaigns were successful beyond his wildest dreams. His ships conquered island after island, and the tribute that flowed into Crete made him the wealthiest king in the Mediterranean.

But Poseidon had not been deceived by the substitution, and his anger at Minos’s betrayal grew like a storm gathering strength over the open ocean. The god decided that the king’s punishment should be as ironic as his crime—since Minos had coveted the bull more than he honored his promise to the gods, the bull would become the instrument of divine justice.

Rather than punish Minos directly, however, Poseidon chose to strike at him through the person he loved most—his wife Pasiphaë. The curse the sea god devised was as cruel as it was unusual: he would make the queen fall desperately, hopelessly in love with the very bull that her husband had refused to sacrifice.

At first, the change in Pasiphaë was subtle. She found herself drawn to visit the royal stables more often than usual, taking an interest in the animals that she had never shown before. The white bull, in particular, seemed to fascinate her, and she would spend long periods simply watching it graze in the royal pastures.

“You seem to have developed quite an interest in our livestock,” Minos observed one day, finding his wife sitting by the fence that enclosed the bull’s pasture.

“It’s such a magnificent creature,” Pasiphaë replied, her voice carrying a strange, dreamy quality. “There’s something almost divine about it, don’t you think?”

Minos felt a flutter of unease at her words, but he dismissed it as the idle fancy of a woman with too much time on her hands. He had no idea that his wife was struggling against a compulsion that grew stronger with each passing day.

As weeks turned to months, Pasiphaë’s obsession with the bull intensified to a degree that terrified her. She knew that what she was feeling was unnatural, wrong, and dangerous, but she seemed powerless to control it. The divine curse had taken hold of her heart and mind so completely that she could think of nothing else.

She tried to fight against the unnatural desire, praying to her father Helios and to all the gods for relief from the terrible compulsion that was consuming her. But the curse was too strong, and gradually it drove her to the brink of madness.

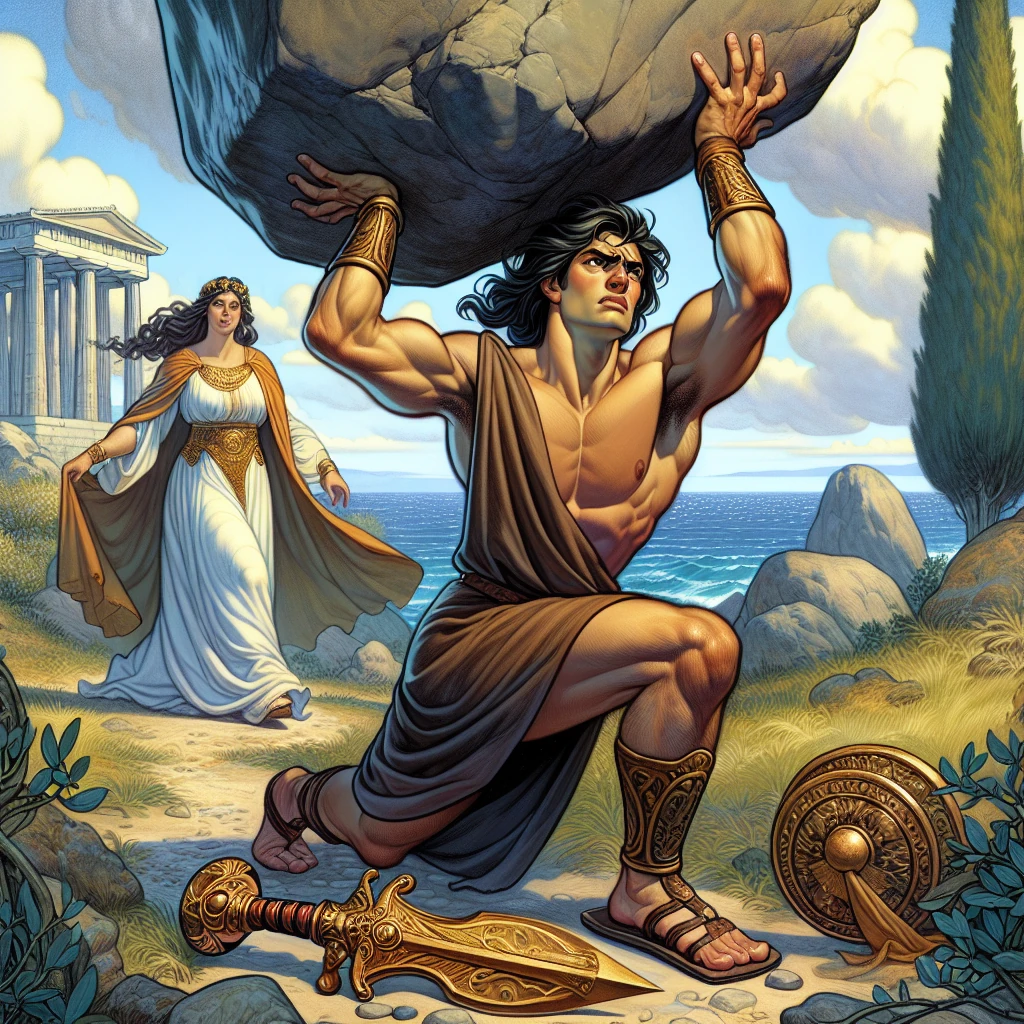

Finally, in desperation, Pasiphaë sought out Daedalus, the master craftsman and inventor who served as the royal architect. Daedalus was known throughout the Greek world for his incredible skill and ingenuity—if anyone could help her, it would be he.

“Great Daedalus,” she said, her voice shaking with shame and desperation, “I am cursed by the gods with a terrible obsession. I need your help to… to satisfy it, or I fear I will go completely mad.”

Daedalus, wise in the ways of both mortal and divine nature, understood immediately what had happened. He had suspected that Minos’s failure to sacrifice the sacred bull would bring divine punishment, but he had not anticipated that it would take such a bizarre and tragic form.

“My queen,” he said gently, “I can see that you are suffering under a divine curse, and I will help you if I can. But I must warn you that some curses, once fulfilled, bring consequences even more terrible than the original affliction.”

But Pasiphaë was beyond reasoning with. The curse had driven her to a point where she was willing to accept any consequence if it would only provide relief from the torment she was experiencing.

Using his incredible skill as a craftsman, Daedalus created a hollow wooden cow, so perfectly crafted and realistic that it was indistinguishable from a living animal. The interior was designed to conceal a human occupant, and the whole contraption was mounted on wheels so that it could be moved easily.

The plan worked exactly as intended, and Pasiphaë’s unnatural union with the sacred bull was consummated. For a brief time, the queen felt relief from the terrible compulsion that had tormented her for so long.

But as Daedalus had warned, the cure proved worse than the curse. From this unnatural union, Pasiphaë conceived and eventually gave birth to a creature that was neither fully human nor fully animal, but a horrible combination of both—the Minotaur, with the body of a man but the head of a bull.

When the monster was born and King Minos saw what his wife had brought into the world, he was horrified not only by the creature itself but by the terrible revelation of what must have happened. The truth of his wife’s curse and its fulfillment became clear to him, and with it came the understanding that this was divine punishment for his broken promise to Poseidon.

Unable to kill the creature—for it was, after all, his wife’s child—but equally unable to allow it to live freely among humans, Minos commissioned Daedalus to construct an elaborate labyrinth beneath the palace. This maze was so complex that anyone who entered it would become hopelessly lost, unable to find their way out.

Into this labyrinth, the Minotaur was placed, where it would live in isolation, fed on the tribute of human victims that Minos would eventually demand from Athens as payment for the death of his son Androgeus.

Pasiphaë, meanwhile, lived the rest of her life in shame and sorrow, knowing that her moment of divine madness had brought a monster into the world and cursed her family for generations to come. The radiant beauty that had once made her the jewel of Crete was dimmed by grief and guilt, and she withdrew from public life, spending her days in prayer and penance.

The curse had achieved exactly what Poseidon had intended—Minos was punished for his impiety through the degradation of his beloved wife and the birth of a monster that would forever be associated with his family name. The king who had thought himself clever enough to cheat the gods learned that divine justice might be delayed, but it could never be avoided.

The white bull that had started it all continued to live in the royal pastures, a constant reminder of the price of broken promises to the gods. Some said that it never aged, remaining as magnificent as the day it had emerged from the sea, a living symbol of divine power and the consequences of mortal pride.

The myth of Pasiphaë became a cautionary tale told throughout the ancient world, warning of what could happen when mortals tried to deceive the gods or failed to honor their sacred obligations. It showed that divine punishment often took forms that mortals could never anticipate, and that the consequences of impiety could extend far beyond the original sinner to affect entire families and future generations.

Yet the story also evoked sympathy for Pasiphaë herself, who was both victim and instrument of divine justice. Her suffering was real and terrible, and her struggle against the unnatural compulsion showed that even under a divine curse, humans retained their capacity for moral understanding and their awareness of right and wrong.

The tale reminded listeners that the gods were not always merciful in their justice, and that sometimes innocents suffered for the sins of others. But it also demonstrated the inexorable nature of divine law—that promises made to the gods must be kept, and that those who thought themselves above divine authority would inevitably learn otherwise.

In the end, the myth of Pasiphaë serves as both a tragedy of individual suffering and a larger meditation on the relationship between mortals and immortals, showing how the actions of kings and queens can have consequences that echo through generations, creating legends that outlast the civilizations that birthed them.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus