The Myth of Minos

Story by: Ancient Greek Mythology

Source: Greek Mythology

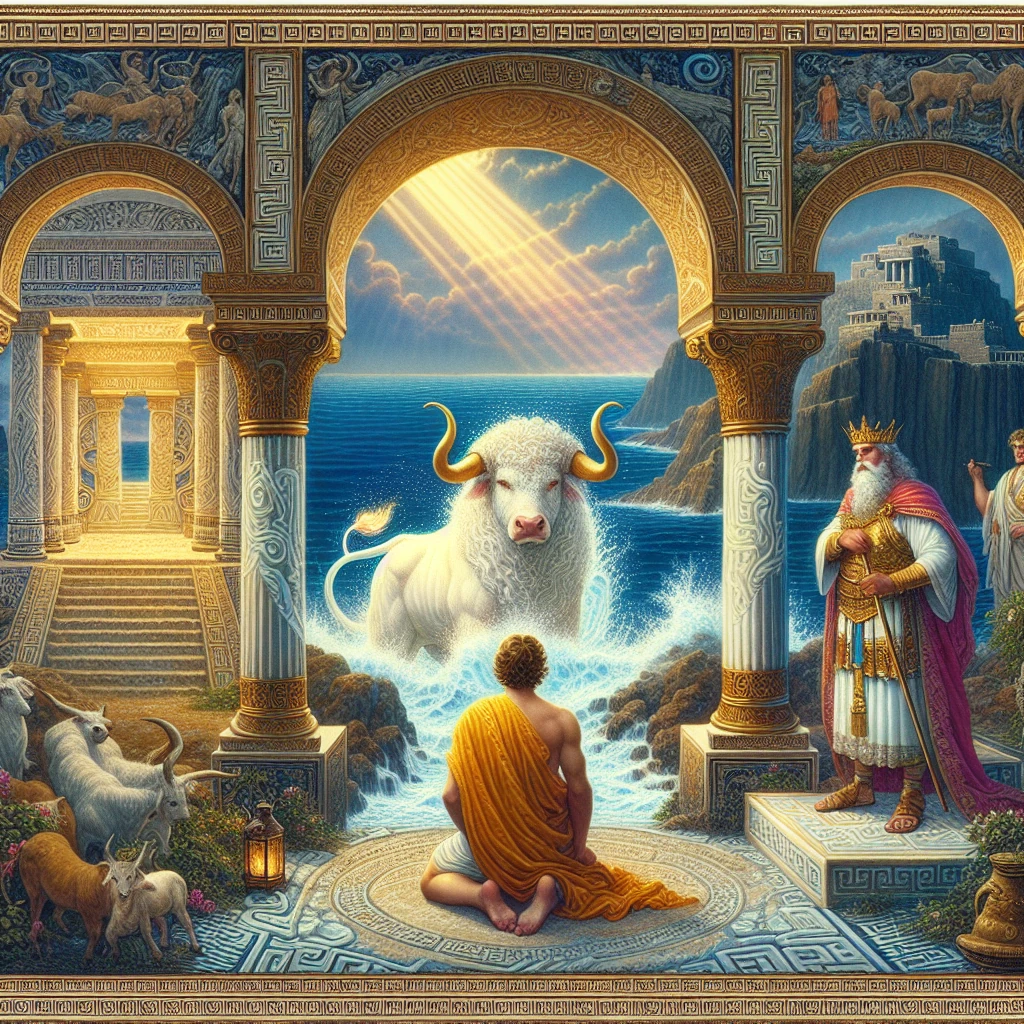

On the island of Crete, where the azure waters of the Mediterranean meet shores of golden sand, there once ruled a king whose name would become synonymous with both justice and terrible curse. Minos was his name, and his story intertwines divine favor with human pride, showing how even the greatest rulers can fall when they forget that their power comes from the gods.

The Prince’s Divine Heritage

Minos was no ordinary mortal. He was the son of Zeus, king of the gods, and Europa, the beautiful princess whom Zeus had courted while transformed into a magnificent white bull. This divine parentage marked Minos from birth as someone destined for greatness, but it also carried the burden of living up to divine expectations.

When Europa gave birth to Minos and his brothers Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon on the island of Crete, the child who would become king was already showing signs of extraordinary wisdom and natural leadership. Even as a young boy, Minos could settle disputes between his playmates with such fairness that adults began bringing their problems to him for resolution.

King Asterius of Crete, who had married Europa and adopted her sons as his own, recognized Minos’s special gifts and groomed him as heir to the throne. Under Asterius’s guidance, Minos learned the arts of rulership, but more importantly, he learned that true authority comes from serving justice rather than serving oneself.

The Contest for the Crown

When King Asterius died, the question of succession arose among his three adopted sons. Each had valid claims to the throne, and each possessed qualities that would make him a capable ruler. Rather than allow civil war to tear Crete apart, Minos proposed a test that would let the gods themselves choose the rightful king.

“My brothers,” Minos declared before the assembled nobles of Crete, “let us not spill family blood over earthly power. I will ask the gods to send a sign showing whom they favor to rule this island. Whoever receives divine endorsement will be acknowledged by the others as the rightful king.”

Minos went to the shore and built an altar to Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes, whose power was particularly strong on islands like Crete. There he made a solemn prayer that would change his destiny forever.

“Great Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, Lord of the Seas,” he called out over the crashing waves, “if you would have me rule over Crete in your name, send me a sign that all may see. Let a bull emerge from your waters, pure white as sea foam, to show your divine approval. This bull I will sacrifice to you immediately, offering back to you the gift you have given.”

The Divine Bull

As Minos finished his prayer, the sea began to churn and foam. From the depths emerged a bull of such magnificent beauty that all who saw it gasped in wonder. It was pure white as Zeus had been when he courted Europa, but its size and majesty surpassed any earthly creature. Its eyes held the depth of the ocean itself, and its presence radiated divine power.

The bull walked calmly from the water and stood before Minos, lowering its great head in acknowledgment of the prince who had called it forth. The assembled Cretans fell to their knees in awe, understanding immediately that they had witnessed a divine miracle.

“Behold!” cried the priests, “Poseidon has answered! The god of the sea has chosen Minos to be our king!”

Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon, though they had hoped for the crown themselves, were honorable men who kept their word. They acknowledged their brother’s divine appointment and pledged their loyalty to him as their king. The coronation of Minos was celebrated throughout Crete as the beginning of a golden age.

The Fatal Temptation

Minos was crowned King of Crete amid great ceremony, and for a time, he proved to be everything his divine parentage had promised. He established laws that were models of fairness, created a naval force that protected Cretan merchants throughout the Mediterranean, and brought prosperity to his island kingdom.

But the magnificent white bull that had secured his throne presented Minos with a terrible temptation. The creature was so beautiful, so perfect, that the king found himself reluctant to fulfill his promise to sacrifice it to Poseidon. Instead, he decided to keep the divine bull for his own herds and sacrifice an ordinary bull in its place.

“Surely,” Minos reasoned to himself, “Poseidon will understand that such a magnificent creature should be preserved rather than killed. I will honor the god with an equally valuable sacrifice, and the divine bull will father a herd that will be the envy of all kingdoms.”

This decision, seemingly reasonable to Minos, was actually a grave betrayal of his sacred oath. He had promised to return the bull immediately to the god who had sent it, and keeping it for himself was an act of prideful dishonesty that would have terrible consequences.

Poseidon’s Curse

Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes, was not deceived by Minos’s substitution. The god who could shake the very foundations of the earth was enraged by the king’s betrayal of their sacred agreement.

“Minos believes he can cheat the gods,” Poseidon declared, his voice like the roar of a tsunami, “He takes my gift and offers me inferior goods in return. Since he values this bull so highly, let him see what his greed and dishonesty will cost him.”

The sea god’s revenge was as creative as it was cruel. Rather than simply punish Minos directly, Poseidon chose to work through the king’s wife, Queen Pasiphaë, daughter of the sun god Helios. The god filled her heart with an unnatural and overwhelming passion for the white bull that Minos had refused to sacrifice.

Pasiphaë, normally a wise and noble queen, found herself consumed by a desire she couldn’t understand or resist. Day and night, she thought only of the magnificent bull, her divine reason overcome by the curse that Poseidon had placed upon her.

The Labyrinth’s Origin

Unable to control her cursed passion, Pasiphaë sought help from Daedalus, the brilliant inventor and craftsman who served in Minos’s court. Daedalus, though horrified by the queen’s request, was compelled to help her through a combination of loyalty, pity, and his own intellectual curiosity about whether such a thing was even possible.

Using his genius for invention, Daedalus created a hollow wooden cow, so perfectly crafted that it could deceive even the divine bull. Through this deception, Pasiphaë was able to fulfill her cursed desire, but the result was even more monstrous than anyone could have imagined.

From this unnatural union was born the Minotaur—a creature with the body of a man but the head and appetite of a bull. The monster was both a symbol of Minos’s broken promise to Poseidon and a living reminder that the gods’ justice, though sometimes delayed, is always terrible when it comes.

The Minotaur was fierce and savage, with an insatiable hunger for human flesh. It could not be killed, for it was partly divine, but neither could it be allowed to roam free among the people of Crete. Minos faced the impossible task of containing a monster that was both his shame and his responsibility.

The Great Labyrinth

Once again, Minos turned to Daedalus for a solution. The master craftsman, realizing that his earlier help had contributed to this disaster, threw himself into creating the most complex structure ever conceived by mortal mind—the Labyrinth.

This was no simple maze, but a vast underground complex beneath the palace of Knossos, with passages so intricate and confusing that even its creator needed a ball of thread to navigate it safely. The walls were made of stone blocks fitted so perfectly that not even a knife blade could slip between them, and the passages twisted and turned in patterns that defied all logic.

At the center of this impossible maze, Minos imprisoned the Minotaur, where it could do no harm to his people but where its terrible hunger could never be satisfied. The monster’s roars echoed through the passages, a constant reminder to the king of the price of breaking faith with the gods.

The Tribute of Athens

As Minos’s power grew and his navy dominated the Mediterranean, he came into conflict with Athens over the death of his son Androgeus. When the Athenians killed the young prince during athletic competitions, Minos declared war on the mainland city, besieging it until its people begged for mercy.

The terms of surrender that Minos imposed revealed how the curse of the Minotaur had changed him. Rather than accepting gold or territory, he demanded a tribute of human lives—seven young men and seven young women from Athens, to be sent to Crete every seven years as food for the monster in the Labyrinth.

This cruel tribute showed how far Minos had fallen from the just ruler he had once been. The king who had once been chosen by the gods for his wisdom was now feeding innocent young people to a monster born from divine curse and his own pride.

The Judge of the Dead

Despite his failures as a mortal king, Minos’s divine heritage and his early reputation for justice were not forgotten by the gods. When he finally died, Zeus appointed him as one of the three judges of the dead in the underworld, alongside his brother Rhadamanthys and Aeacus.

In this role, Minos found redemption for his earthly mistakes. His perfect knowledge of justice, combined with his understanding of how pride and poor choices can lead to ruin, made him an ideal judge of human souls. He could see through excuses and rationalizations to the truth of each person’s character and actions.

The irony was complete: the king who had broken faith with a god and become the source of a terrible curse was now entrusted with determining the eternal fate of other souls based on their faithfulness and moral choices.

The Eternal Lesson

The myth of Minos teaches us that divine favor comes with divine responsibility, and that breaking faith with the gods—or with the principles they represent—always carries consequences, though these may not be immediately apparent.

Minos’s story shows how pride can corrupt even the best intentions. His desire to keep the beautiful bull seemed reasonable to him, a small adjustment to his agreement with Poseidon. But this seemingly minor betrayal led to a curse that destroyed his family’s peace and turned him from a just ruler into a tyrant who fed innocent lives to a monster.

The tale also demonstrates that our choices affect not only ourselves but those we love. Minos’s betrayal of Poseidon led to Pasiphaë’s curse, the birth of the Minotaur, and ultimately the deaths of countless young Athenians. Personal failures have public consequences, especially for those in positions of power.

Yet the story offers hope as well. Minos’s appointment as a judge in the underworld suggests that understanding our failures can lead to wisdom, and that even those who have made terrible mistakes can find redemption through serving justice faithfully.

The Living Legacy

Today, the name of Minos is remembered not only for his failures but for his contributions to justice and law. The Minoan civilization that bore his name became renowned for its art, culture, and relatively peaceful society. Archaeological evidence suggests that ancient Crete was indeed a maritime power with remarkable achievements in architecture and engineering.

The myth reminds us that true leadership requires humility before divine power—or before the moral principles that govern human society. Minos’s early success came from his recognition that his authority came from the gods, but his downfall began when he started believing that his cleverness could improve upon divine commands.

And so the story of King Minos continues to resonate, a tale of how divine gifts can become curses when mixed with human pride, and how the price of broken promises is always higher than we imagine when we make the choice to break them.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus