The Myth of Io

Story by: Ancient Greek Mythology

Source: Greek Mythology

In the ancient city of Argos, where the goddess Hera was worshipped with particular devotion and her magnificent temple dominated the sacred hill, there served a young priestess whose beauty was so extraordinary that it would attract the attention of the gods themselves, bringing both wonder and terrible suffering into her life. This was Io, daughter of the river god Inachus, and her story would take her on a journey across the known world, transformed and tormented, yet ultimately destined for a glorious fate.

Io was the perfect priestess for Hera’s temple—pure of heart, devoted in her worship, and possessed of a beauty that seemed almost divine in its perfection. Her long, dark hair caught the light like polished obsidian, her eyes held the deep mystery of forest pools, and her grace in performing the sacred rituals made even the most casual observers pause in wonder.

As the daughter of a river god, Io possessed a natural affinity for the sacred duties she performed. She understood the proper forms of worship, the correct pronunciation of ancient prayers, and the intricate symbolism of the rituals that honored Hera as queen of the gods and protector of marriage and family.

The young priestess was content with her life of service, finding deep satisfaction in her devotion to the goddess and her role in maintaining the sacred traditions of Argos. She had no desire for the ordinary pleasures of mortal women—marriage, children, and domestic concerns seemed pale compared to the honor of serving the queen of heaven herself.

But high on Mount Olympus, Zeus had noticed the beautiful priestess during one of his periodic surveys of the mortal world. The sight of Io performing her sacred duties, moving with ethereal grace through the temple precincts, ignited a desire in the king of the gods that would not be denied.

Zeus was particularly intrigued by the irony of the situation—here was a priestess dedicated to his wife, a woman whose purity and devotion to Hera made her seem almost untouchable. The challenge of winning such a devoted servant of his queen only intensified his desire.

At first, Zeus contented himself with watching Io from afar, appearing to her in dreams as a mysterious divine figure who spoke of love and destiny. These dreams were so vivid and compelling that Io began to look forward to sleep, finding her dream-encounters more real and meaningful than her waking life.

“Beautiful Io,” the dream-figure would say, “you are wasted in service to others. You were meant for greater things, for divine love and immortal glory.”

Io would wake from these dreams confused and troubled, uncertain whether they were mere fantasies of her sleeping mind or genuine divine visions. She increased her prayers and rituals, hoping that Hera would clarify the meaning of these strange nocturnal experiences.

But Zeus was not content to remain merely a dream-figure. One day, as Io was walking alone in a grove sacred to Hera, gathering flowers for the temple altars, Zeus appeared to her in his most appealing mortal form—a handsome young man with eyes that held the depth of the sky and a presence that radiated power and authority.

“Do not be afraid, beautiful Io,” he said, his voice carrying a hypnotic quality that made resistance difficult. “I am the one who has been visiting your dreams. I have come to make those dreams reality.”

Io tried to flee, recognizing instinctively that this encounter was dangerous, but Zeus pursued her with divine persistence. Using his power over weather and nature, he surrounded her with darkness, creating a cloud that hid them from mortal eyes while he pressed his suit.

Despite her protests and her sacred vows, Io found herself overcome by Zeus’s divine charisma and power. The union that followed was not entirely against her will, for Zeus had the ability to inspire genuine passion even while overwhelming mortal resistance, but it was certainly a violation of her sacred duties and her commitment to chastity.

When Zeus departed, leaving Io alone in the grove with the terrible knowledge of what had transpired, the young priestess was devastated. She had betrayed her goddess, broken her sacred vows, and compromised everything she had held dear.

But her suffering had only just begun. High on Mount Olympus, Hera had noticed her husband’s absence and the strange darkness that had briefly covered the grove near her temple in Argos. The queen of the gods had long experience with Zeus’s infidelities, and her divine instincts told her that he had been up to his old tricks once again.

Hera descended to earth to investigate, arriving at the grove just as Zeus was preparing to depart. Seeing his wife approaching, Zeus panicked and attempted to hide the evidence of his transgression in the most expedient way possible—he transformed Io into a beautiful white cow.

When Hera arrived at the grove, she found her husband standing innocently beside a magnificent heifer, whose eyes seemed strangely intelligent and whose bearing suggested something more than ordinary animal nature.

“My dear wife,” Zeus said, trying to appear casual despite his obvious nervousness, “what brings you to this remote place?”

Hera studied the cow with suspicious eyes, noting its unusual beauty and the way it seemed to be trying to communicate with her. “What a lovely animal,” she said with deceptive sweetness. “Where did it come from?”

“Oh, it just appeared,” Zeus replied lamely. “A wild cow, I suppose, drawn by the sacred nature of this grove.”

But Hera was far too experienced in her husband’s deceptions to be fooled by such transparent lies. She knew perfectly well that the cow was a transformed woman, almost certainly Zeus’s latest conquest.

“How wonderful,” Hera said, her voice taking on a dangerous edge. “Since it appeared so mysteriously in my sacred grove, surely it must be intended as a gift for me. I shall accept this beautiful cow as an offering to honor my divine status.”

Zeus found himself trapped by his wife’s cunning. He could hardly refuse to give her the cow without revealing that it was actually a transformed woman, but giving it to her would place Io completely under Hera’s power.

With no choice but to maintain his deception, Zeus reluctantly agreed to let Hera take the cow. “Of course, my dear,” he said through gritted teeth. “It would be my pleasure to offer you this… animal… as a token of my respect.”

Hera accepted the cow with a smile that would have chilled the heart of anyone who truly understood her nature. She knew exactly what she had received, and she intended to make both Zeus and his latest victim pay for their transgression.

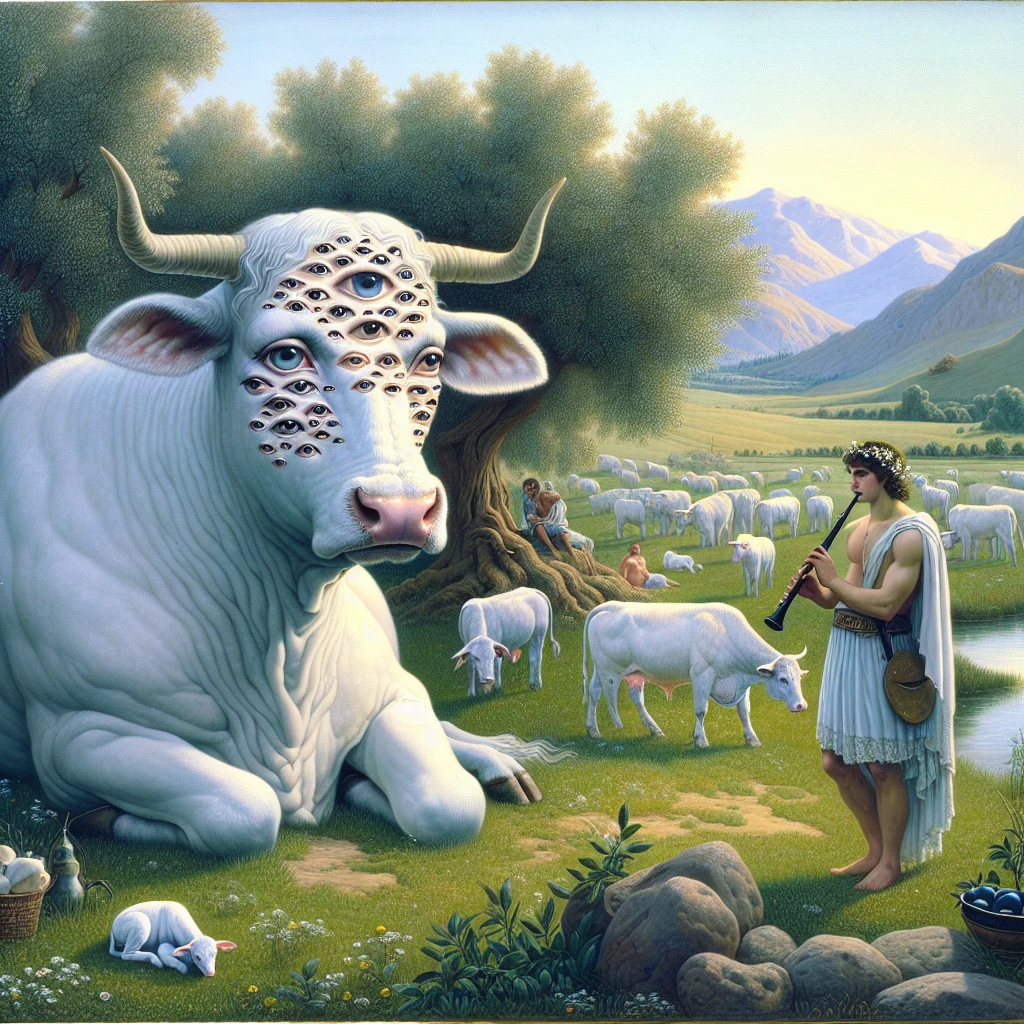

To ensure that Zeus could not easily reverse the transformation, Hera placed the cow under the guard of Argus Panoptes, a giant with one hundred eyes scattered across his body. Argus was the perfect guardian—with so many eyes, he could keep watch continuously, for while some eyes slept, others remained awake and alert.

“My faithful Argus,” Hera commanded, “I place this cow in your care. Watch it constantly, never let it out of your sight, and ensure that no one approaches it without my permission.”

Poor Io, trapped in the body of a cow but retaining her human consciousness and memory, found herself imprisoned under the constant surveillance of the hundred-eyed giant. She could not speak to explain her plight, could not write to communicate her identity, and could only low mournfully as she tried desperately to make someone understand what had happened to her.

The worst part of her torment was when her father, the river god Inachus, came looking for his missing daughter. Io tried frantically to communicate her identity, pawing letters in the dirt with her hooves and trying to make him understand through her behavior that she was his beloved child.

Finally, Inachus began to suspect the truth. The cow’s obvious intelligence, its emotional response to his presence, and its attempts at communication convinced him that this was no ordinary animal.

“My daughter,” he whispered to the cow when Argus was momentarily distracted, “if this is truly you, give me a sign.”

Io managed to spell out her name in the dust with her hoof, and Inachus wept to see his beautiful daughter trapped in such a form. But there was nothing he could do—Argus was too powerful, and Hera’s protection made the giant nearly invincible.

Meanwhile, Zeus was growing increasingly frustrated with his inability to help Io or to counter his wife’s revenge. He knew that direct action would only escalate the conflict and bring worse suffering upon the transformed priestess, but he could not bear to see her torment continue indefinitely.

Finally, Zeus decided to act indirectly. He summoned his son Hermes, the messenger god and patron of thieves and tricksters, and gave him a mission that would require all his cunning and skill.

“My son,” Zeus said, “I need you to kill Argus and free the cow he guards. But you must do it in such a way that Hera cannot claim I acted directly against her will.”

Hermes accepted the challenge with enthusiasm. He was always eager for tasks that required cleverness and stealth, and the prospect of outwitting the hundred-eyed giant appealed to his mischievous nature.

Disguising himself as a simple shepherd, Hermes approached Argus and struck up a conversation. The giant, who spent his days in solitary watchfulness, was grateful for the company and invited the stranger to sit with him.

“I have with me my pipes,” Hermes said, producing a set of reed instruments. “Would you like to hear some music to pass the time?”

Argus agreed, and Hermes began to play the most beautiful and soothing melodies he could create. But this was no ordinary music—it was divine music, charged with the power to induce sleep and drowsiness in any listener.

As Hermes played, he began to tell stories as well, weaving long, rambling tales designed to be both engaging and soporific. One by one, Argus’s hundred eyes began to close, lulled by the combination of beautiful music and hypnotic storytelling.

When Hermes was certain that all of Argus’s eyes were finally closed in sleep, he acted swiftly. Drawing his sword, he struck off the giant’s head, killing him instantly and freeing Io from her constant surveillance.

But Hera’s revenge was far from over. When she discovered that Argus had been killed and the cow had escaped, her fury knew no bounds. She honored her faithful servant by taking his hundred eyes and placing them in the tail of the peacock, which became her sacred bird.

For Io, however, she devised an even more terrible punishment. She sent a gadfly—a biting insect that would torment the cow with its constant stings, driving her to wander endlessly across the earth in a desperate attempt to escape the pain.

The gadfly’s stings were not merely physical torment but carried with them a divine madness that made rest impossible. Io was driven to run continuously, crossing rivers, climbing mountains, and traversing entire countries in her attempts to escape the relentless insect.

Her journey took her through many lands that would later bear names connected to her passage. She crossed the strait between Europe and Asia, which became known as the Bosphorus (meaning “cow’s crossing”), and wandered through regions that would remember her in their mythology and geography.

Everywhere she went, Io’s suffering moved those who saw her. Local people would try to help the tormented cow, offering food and water, but the gadfly would always drive her onward before she could find real relief.

During her wanderings, Io encountered other victims of divine punishment, including Prometheus, who was chained to a rock for giving fire to humanity. The Titan, who had the gift of prophecy, recognized her despite her transformation and offered her words of comfort and hope.

“Beautiful Io,” Prometheus said, “I know your suffering, for I too have experienced the wrath of Zeus and Hera. But take heart—your torment will not last forever. You will wander to the ends of the earth, but eventually you will find peace in Egypt, where Zeus will restore your human form and you will bear a son who will father a line of heroes.”

These words gave Io the strength to continue her seemingly endless journey. She wandered through the regions that would later be known as Europe and Asia, her passage marking the boundaries between continents and her story becoming woven into the mythology of every land she crossed.

Finally, after years of wandering, Io reached the banks of the Nile River in Egypt. There, exhausted and nearly driven mad by her long torment, she collapsed beside the sacred waters.

Zeus, who had been watching her suffering with growing remorse, finally decided that enough punishment had been inflicted. He appeared to Hera and made a solemn promise that he would never again pursue Io or any other of her priestesses.

Satisfied that her point had been made, Hera agreed to lift her curse. The gadfly disappeared, and Zeus gently restored Io to her human form. But the years of wandering as a cow had changed her—she was no longer the innocent young priestess who had served in Hera’s temple, but a woman who had seen the world and suffered greatly for the gods’ conflicts.

In Egypt, Io was welcomed and honored, eventually bearing Zeus a son named Epaphus, who was said to be born from Zeus’s touch alone. Epaphus grew to become a great king of Egypt, and from his line would come many heroes, including the famous Perseus and, much later, Heracles himself.

Io lived out her days in Egypt as a honored queen and goddess, worshipped by the Egyptians as Isis, a deity of motherhood and magic. Her transformation from victim to goddess represented the ultimate triumph over suffering and the way that even the most terrible ordeals can lead to wisdom and eventual glory.

The myth of Io serves as both a cautionary tale about the dangers of attracting divine attention and a story of ultimate redemption through endurance. Her journey across the known world became a symbol of the wanderings that all souls must sometimes undertake in their search for peace and understanding.

Her story also illustrates the complex relationships between the gods, showing how their conflicts inevitably involved innocent mortals who paid the price for divine jealousy and passion. Yet it also demonstrates that even the most terrible suffering can lead to transformation and eventual glory for those who endure with courage and hope.

The geographical elements of Io’s story—the naming of the Bosphorus and other landmarks—helped ancient Greeks understand their world and their place in it, while her transformation into the Egyptian goddess Isis created connections between Greek and Egyptian religious traditions that would influence both cultures for centuries to come.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus