The Judgement of Paris

Story by: Greek Mythology

Source: Ancient Greek Legends

The Judgement of Paris

Long before the great walls of Troy echoed with the clash of bronze and the cries of war, before heroes like Achilles and Hector became legends, there was a single moment of choice that would shape the destiny of gods and mortals alike. It began, as many great troubles do, with vanity, jealousy, and a golden apple.

The story opens at the wedding of Peleus, a mortal hero, and Thetis, a sea nymph whose beauty had caught the attention of both Zeus and Poseidon. When it was prophesied that Thetis would bear a son greater than his father, both gods quickly arranged for her to marry a mortal instead, ensuring that her child would not threaten their divine supremacy.

All the gods and goddesses were invited to this grand wedding celebration—all except one. Eris, the goddess of discord and strife, had been deliberately excluded from the guest list, for the other deities knew that wherever Eris went, trouble followed close behind.

But Eris was not one to accept such a slight quietly. As the wedding feast reached its height, with gods and mortals celebrating together in harmony, the uninvited goddess appeared at the edge of the gathering. In her hand, she held a golden apple of surpassing beauty, its surface gleaming like captured sunlight.

“Since I was not invited to share in this joy,” Eris called out with a smile that promised mischief, “I bring you all a gift to remember me by!”

With that, she hurled the golden apple into the midst of the celebration, where it rolled to a stop before the high table where the most important guests were seated. As the apple caught the light, words appeared on its surface, written in letters that seemed to glow with their own fire:

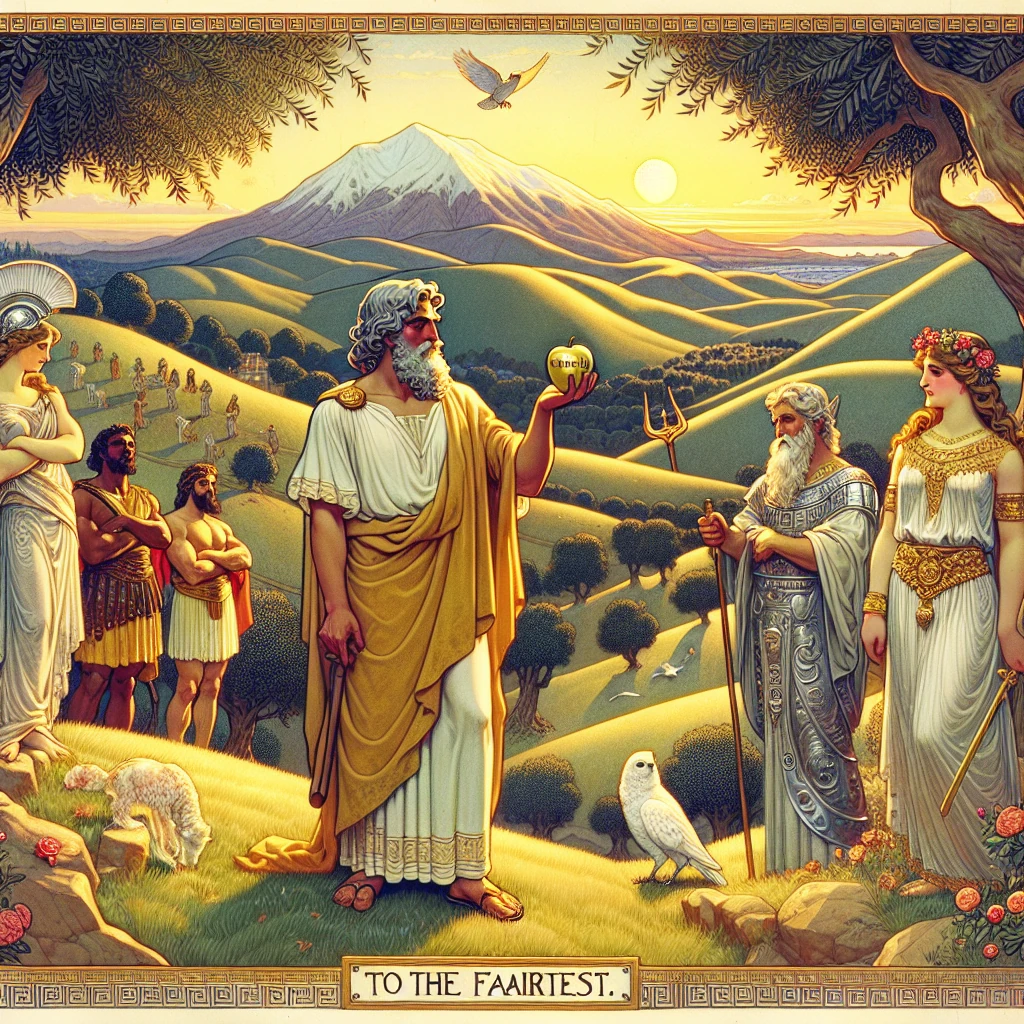

“To the Fairest”

Instantly, the celebration fell silent. Every eye in the hall was fixed on the apple, but three goddesses rose from their seats with particular interest: Hera, queen of the gods and wife of Zeus; Athena, goddess of wisdom and warfare; and Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty.

“Clearly, this apple is meant for me,” declared Hera, her voice carrying the authority of her position. “I am the queen of Olympus, the wife of Zeus himself. Who could be fairer than the queen of the gods?”

“Beauty means nothing without wisdom,” countered Athena, her grey eyes flashing. “True fairness comes from the mind, not merely appearance. As the goddess of wisdom, I am surely the fairest.”

Aphrodite laughed, a sound like silver bells in the wind. “My dear sisters, how touching that you should think so highly of yourselves. But surely the apple belongs to me, for am I not the very essence of beauty itself? I am beauty personified—to whom else could it belong?”

What followed was an argument that shook the very foundations of Mount Olympus. Each goddess made her case with increasing passion, their voices growing louder and their tempers shorter. The other gods and goddesses looked on in dismay, for they knew that no matter who was chosen, the other two would never forget the slight.

Finally, Zeus himself rose from his throne, his face grave with concern.

“Enough!” the king of gods commanded, and thunder rumbled overhead. “This argument must end, but I cannot be the one to judge between you. The matter is too delicate, and the consequences too great. We need an impartial judge—someone with no stake in our divine politics.”

Zeus pondered for a moment, then his expression brightened slightly. “I know of such a person. On Mount Ida, near the great city of Troy, there lives a young shepherd named Paris. He is known for his fairness and his keen eye for beauty. Let him decide which of you three is fairest.”

The three goddesses agreed to this proposal, though none was entirely pleased with the idea of being judged by a mortal. But it was better than allowing Zeus to choose, for they knew his decision would be influenced by his desire to keep peace among his family.

What none of them knew was that Paris was not merely a shepherd. He was, in fact, a prince of Troy, son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba. Before his birth, Hecuba had dreamed that she would give birth to a burning torch that would destroy the city of Troy. Terrified by this prophecy, Priam had ordered the infant Paris to be abandoned on Mount Ida to die.

But the baby had been found and raised by shepherds, growing up strong and handsome, with no knowledge of his royal heritage. He had become known throughout the region for his wisdom in settling disputes and his reputation for fairness in all his dealings.

On the fateful day, Paris was tending his flocks on the slopes of Mount Ida when suddenly the air shimmered with divine light. Before him materialized three figures of such beauty and majesty that he fell to his knees in awe.

“Rise, Paris of Troy,” said Hermes, messenger of the gods, who had accompanied the goddesses to earth. “Zeus has chosen you for a great honor. You must decide which of these three goddesses is the fairest and award this golden apple to her.”

Paris looked from one goddess to another, his shepherd’s heart pounding with the weight of the responsibility placed upon him. Each was beautiful beyond mortal comprehension, but in completely different ways.

Hera stood tall and regal, her dark hair crowned with a diadem that caught the light like stars. Her presence radiated power and authority, the unmistakable bearing of a queen. When she spoke, her voice was rich and commanding.

“Young Paris,” Hera said, “choose wisely, and I will make you the most powerful ruler in the world. You shall have dominion over vast kingdoms, command mighty armies, and your name will be remembered as the greatest king who ever lived.”

Athena stepped forward next, her grey eyes bright with intelligence. She wore armor that gleamed like silver, and wisdom seemed to flow from her very presence.

“Paris,” Athena offered, “award the apple to me, and I will give you wisdom beyond all mortals and victory in every battle. You shall be the greatest warrior and strategist who ever lived, unconquerable in war and unmatched in counsel.”

Finally, Aphrodite approached, and Paris felt his breath catch in his throat. Her beauty was like nothing he had ever imagined—not merely physical perfection, but the very essence of desire and love made manifest.

“Dear Paris,” Aphrodite said, her voice like honey, “what good are power and wisdom without love? Choose me, and I will give you the love of the most beautiful woman in the world. She shall be your wife, and your love will be the stuff of legend.”

Paris stood in silence for a long moment, considering each offer. Power was tempting—who would not want to rule kingdoms and command armies? Wisdom and victory in battle were appealing too—what man did not dream of being a great hero?

But as he looked at Aphrodite, Paris thought of the loneliness of his shepherd’s life, of the empty evenings by his fire with only the stars for company. Love, he realized, was what he wanted most of all.

“I choose Aphrodite,” Paris declared, holding out the golden apple to the goddess of love. “Beauty that inspires love is the fairest of all.”

Aphrodite accepted the apple with a smile that could have melted stone, while Hera and Athena’s faces darkened with fury.

“You have chosen well, my dear Paris,” Aphrodite said. “And I will keep my promise. The most beautiful woman in the world is Helen, daughter of Zeus and wife of Menelaus, king of Sparta. She shall be yours.”

“But she is already married!” Paris protested.

Aphrodite’s smile grew more mysterious. “Love finds a way, my prince. Trust in that.”

As the goddesses vanished in flashes of light, Paris did not notice the dark looks that Hera and Athena exchanged. Both goddesses swore in their hearts that they would have their revenge on Troy and all its people for this insult.

Not long after, Paris discovered his true identity as a prince of Troy and returned to his father’s court. There, he was welcomed back into the royal family and given a place of honor. When diplomatic missions needed to be undertaken, Paris volunteered to travel to Sparta to negotiate with King Menelaus.

It was there that he first laid eyes on Helen, and the moment he saw her, he understood why Aphrodite had called her the most beautiful woman in the world. Helen possessed an ethereal beauty that seemed almost divine—golden hair that caught light like spun sunbeams, eyes blue as the Aegean Sea, and features so perfect they could have been carved by the gods themselves.

More than her physical beauty, Helen possessed a grace and kindness that drew people to her like flowers turning toward the sun. When she spoke, her voice was musical; when she moved, it was like watching a goddess walk among mortals.

Under Aphrodite’s influence, Helen found herself inexplicably drawn to the handsome Trojan prince. Despite her marriage to Menelaus, she felt a connection to Paris that she had never experienced before. It was as if her heart recognized something in him that her mind could not explain.

When Paris proposed that she flee with him to Troy, Helen was torn between duty and desire, between the life she knew and the love she had found. But Aphrodite’s power was strong, and love—or at least the divine compulsion that felt like love—won out over duty.

In the dark of night, Helen left Sparta with Paris, taking with her much of the royal treasure and abandoning her husband, her daughter, and her homeland.

When Menelaus discovered his wife’s flight, his rage was terrible to behold. He called upon his brother Agamemnon and all the kings of Greece who had once sworn to protect Helen’s marriage. The result was the greatest military expedition the world had ever seen—a thousand ships carrying the finest warriors of Greece across the wine-dark sea to demand Helen’s return.

But Paris, blinded by love and Aphrodite’s gift, refused to give her up. “I have found true love at last,” he declared. “No army on earth will make me surrender her.”

Thus began the Trojan War, a conflict that would rage for ten long years, claiming the lives of countless heroes and ultimately destroying the great city of Troy itself. All because of a golden apple, three vain goddesses, and a young man’s choice between power, wisdom, and love.

The ancient Greeks told this story as a warning about the power of vanity and the dangerous consequences of seemingly small choices. They believed that the gods used mortals as pawns in their own games, but they also recognized that mortals bore responsibility for their own decisions.

In choosing love over power or wisdom, Paris followed his heart—but he failed to consider the cost his choice would have for others. His decision brought him the woman he desired, but it also brought war, destruction, and ultimately death to himself, to Helen, and to countless others.

The Judgment of Paris reminds us that our choices, however personal they may seem, can have consequences far beyond what we imagine. It teaches us to consider not just what we want, but what our wanting might cost—both for ourselves and for those around us.

And perhaps most importantly, it suggests that when the gods offer us gifts, we should be very careful what we wish for—because we just might get it.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus