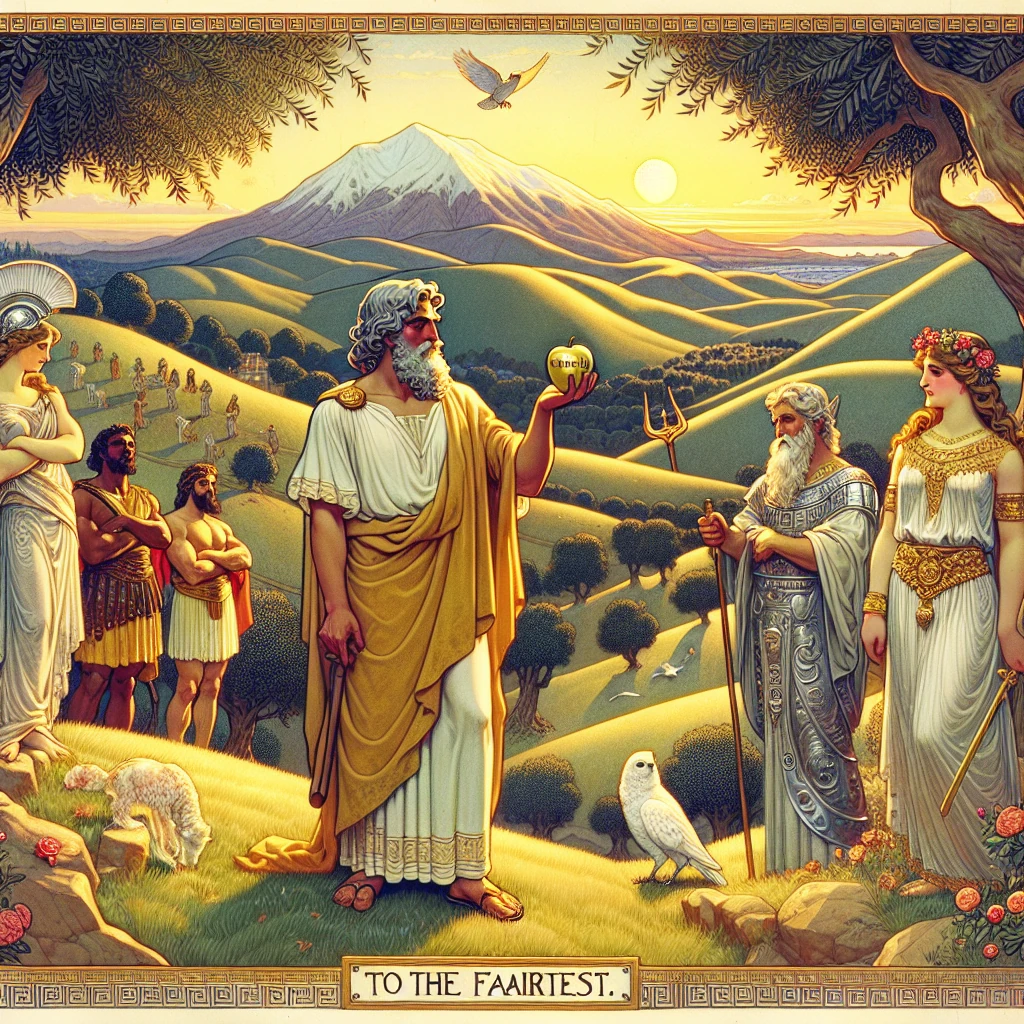

The Fall of Troy

Story by: Homer and Various Greek Poets

Source: Greek Mythology

After ten long years of siege, the great city of Troy stood battered but still defiant behind its mighty walls. The war that had begun with Paris’s abduction of Helen had claimed countless lives on both sides, including some of the greatest heroes of the age. Yet despite the Greeks’ superior numbers and the intervention of various gods on both sides, the city remained unconquered. It would take cunning rather than courage, deception rather than direct assault, to finally bring down the proud citadel of Priam.

The Death of Hector

The beginning of Troy’s end came with the fall of its greatest defender. Prince Hector, eldest son of King Priam and the bulwark of Trojan hopes, had been slain by the Greek hero Achilles in single combat outside the city walls. The death of Hector sent shockwaves through both the Trojan and Greek camps, for he had been universally respected as the noblest and most honorable warrior of the war.

In the palace of Troy, Queen Hecuba wept inconsolably for her son, while King Priam aged visibly with grief. The old king’s shoulders, which had borne the weight of defending his city for a decade, now seemed to buckle under the added burden of personal loss.

“Hector was the shield wall that protected us all,” Priam said to his remaining sons as they gathered in the throne room. “Without him, we must find new ways to defend our city, new strategies to keep the Greeks at bay.”

Paris, whose actions had brought about the war, felt the weight of responsibility and guilt more heavily than ever. “Father,” he said, his voice thick with emotion, “I know that I am the cause of all this suffering. If you wish, I will face Menelaus in single combat and end this war once and for all.”

But Priam shook his head. “The war has grown beyond its original cause, my son. Even if Helen were returned tomorrow, I fear the Greeks would not depart. They have invested too much blood and treasure to leave empty-handed.”

Indeed, the war had taken on a life of its own. What had begun as a quest to retrieve a stolen queen had become a test of Greek honor and Trojan independence. Cities that allied with Troy had been destroyed, and Greek kings who had committed their armies could not return home without victory to show for their sacrifices.

The Arrival of Reinforcements

Despite Hector’s death, Troy was not yet defenseless. Allies from across the known world continued to arrive, drawn by bonds of friendship, fear of Greek expansion, or simply the promise of glory in battle. Among the most notable of these was Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, who arrived with a contingent of her warrior women.

Penthesilea was a formidable figure—tall, strong, and skilled with both sword and bow. Her armor gleamed in the sunlight as she rode through Troy’s gates, her presence lifting the spirits of the city’s defenders.

“I come to honor the memory of noble Hector,” she declared to King Priam in the palace’s great hall. “The Amazons have long respected Trojan courage, and we will not see your city fall without adding our strength to its defense.”

For a brief time, the arrival of the Amazons seemed to turn the tide. Penthesilea led successful sorties against the Greek camps, and her warriors proved themselves fierce opponents. But fate was not on Troy’s side. In a climactic battle, Penthesilea faced Achilles in single combat and, despite her skill and courage, was slain by the Greek hero.

Her death was followed by that of Memnon, king of the Ethiopians, another ally who had come to Troy’s aid. Memnon was said to be a son of Eos, the goddess of dawn, and his warriors were among the most feared in the ancient world. Yet he too fell to Achilles, adding to the Greek hero’s already legendary reputation.

The Death of Achilles

But the gods had decreed that Achilles himself would not survive to see Troy’s fall. During a battle near the Scaean Gate, Paris—aided by the god Apollo—loosed an arrow that found its mark in Achilles’ heel, the one spot where the great warrior was vulnerable.

The death of Achilles sent shockwaves through the Greek camp. Ajax and Odysseus fought desperately to recover his body from the battlefield, while the Trojans pressed their advantage. For a moment, it seemed as though the Greeks might break and flee to their ships.

“Achilles is dead!” the cry went up from both armies. For the Greeks, it was a lament; for the Trojans, a cheer of triumph. But experienced warriors on both sides knew that the war was far from over.

The Greeks held a magnificent funeral for their greatest hero, burning his body on a pyre that could be seen from Troy’s walls. His divine armor, crafted by Hephaestus himself, became the subject of fierce dispute between Ajax and Odysseus, ultimately contributing to Ajax’s own tragic end when the armor was awarded to Odysseus.

Paris’s Final Battle

With Achilles dead, Paris found himself facing a different kind of battle. The Trojan prince, who had always been more lover than warrior, was wounded by a poisoned arrow shot by Philoctetes using the bow of Heracles. The wound festered and brought him close to death.

In desperation, Paris sought out his first wife, the nymph Oenone, whom he had abandoned for Helen years before. Oenone possessed the knowledge of healing herbs that could save him, but when Paris came to her, she was consumed with bitterness.

“You abandoned me for a mortal woman,” Oenone said coldly as Paris lay dying before her. “You chose Helen over me, and now you expect me to save you? Let Helen heal you, if she can.”

Paris died from his wound, and with him died any hope of a negotiated peace. Helen, now a widow, remained in Troy under the protection of Deiphobus, another of Priam’s sons who had married her according to Trojan custom.

The Greek Desperation

After ten years of siege, the Greeks found themselves in an increasingly difficult position. Their supplies were running low, their men were growing restless, and many questioned whether Troy could ever be taken by conventional means. The city’s walls remained strong, and its defenders, though depleted, still fought with the courage of men defending their homes and families.

Agamemnon, the Greek commander-in-chief, called a council of war to discuss their options. “We cannot maintain this siege indefinitely,” he admitted to his assembled leaders. “Our supplies grow thin, and murmurs of mutiny increase with each passing day. We must find a new approach, or we risk losing everything we have gained.”

Diomedes, one of the most practical of the Greek commanders, voiced what many were thinking: “Perhaps it is time to consider retreat. We have won great glory in this war, and we have avenged many insults. There is no shame in acknowledging that Troy’s walls are stronger than our siege engines.”

But Odysseus, known throughout the Greek camp for his cunning intelligence, had been considering a different approach entirely. “We have tried to take Troy by force of arms for ten years,” he said thoughtfully. “Perhaps it is time to try taking it by force of wit.”

The Conception of the Horse

Odysseus’s plan was audacious in its simplicity and deception. Rather than attempting to break down Troy’s walls or starve out its defenders, the Greeks would trick the Trojans into opening their gates willingly.

“We will build a great wooden horse,” Odysseus explained to the assembled Greek leaders. “Inside its hollow belly, we will hide our finest warriors. The rest of our army will pretend to sail away, leaving only the horse behind as an apparent offering to the gods.”

The plan was met with skepticism from some quarters. “And why would the Trojans bring this horse into their city?” asked Nestor, the elderly king of Pylos whose wisdom was respected throughout the camp.

“Because we will leave behind a story,” Odysseus replied with a cunning smile. “A tale that plays upon their vanity and their hope. The horse will be presented as an offering to Athena, too large to be taken through Troy’s gates except by the deliberate action of the Trojans themselves. If they bring it into their city, it will ensure their victory in any future war. If they leave it outside, they risk offending the goddess.”

Agamemnon, desperate for any strategy that might break the deadlock, agreed to try Odysseus’s plan. “But who will build such a thing? And who will volunteer to hide inside it, knowing that if the plan fails, they will be trapped inside Troy with no hope of rescue?”

For the construction, they turned to Epeius, a skilled craftsman who had previously shown talent for woodworking. As for volunteers to hide inside the horse, there was no shortage of brave men willing to risk everything for the chance to finally end the war.

The Construction of the Trojan Horse

The building of the great wooden horse took place on the beach where the Greek ships had been drawn up for ten years. Epeius worked with a team of carpenters and artisans, creating a structure that was both imposing and beautiful—a creation worthy of being seen as an offering to the gods.

The horse stood as tall as a small building, its form carefully crafted to resemble a living animal. Its eyes were made of precious stones that seemed to gleam with life, and its mane was carved with such skill that it appeared to flow in an unfelt wind. Most importantly, its belly was hollow, with a hidden entrance large enough to admit armed warriors.

While the horse was being built, the Greeks also prepared for the deception that would make the plan work. Sinon, a Greek soldier chosen for his ability to lie convincingly, volunteered to remain behind when the main army departed. His role would be to convince the Trojans that the horse was indeed a sacred offering and that bringing it into the city would bring them divine favor.

“Remember,” Odysseus instructed Sinon as the plan neared completion, “you must allow yourself to be captured. You must convince them that you have been abandoned by your own people. Only then will they trust your story about the horse’s purpose.”

The False Departure

When the horse was complete, Odysseus selected the men who would hide inside it. Among them were some of the greatest remaining Greek heroes: Menelaus, seeking to reclaim his wife; Diomedes, the fierce warrior; Neoptolemus, young son of the dead Achilles; and Odysseus himself, who would not ask others to take risks he would not share.

As these chosen warriors climbed into the horse’s belly through its concealed entrance, the rest of the Greek army began their false departure. They burned their camps, loaded their ships, and sailed away as if finally admitting defeat. However, they did not go far—only to the nearby island of Tenedos, where they could wait hidden until the time came to return.

From Troy’s walls, the Trojans watched in amazement as their enemies of ten years sailed away, leaving only the strange wooden horse standing on the empty beach.

“Can it be true?” King Priam asked as he surveyed the scene from his palace tower. “Have the Greeks truly given up their siege?”

“It appears so,” replied Deiphobus, who had married Helen after Paris’s death. “But we must be cautious. This could be some kind of trick.”

Indeed, many Trojans were suspicious of the sudden Greek departure and the mysterious horse left behind. Some, led by the priest Laocoon, urged immediate destruction of the wooden structure.

Sinon’s Deception

It was then that Sinon played his crucial role. Trojan soldiers found him hiding near the horse, apparently abandoned by his countrymen. When brought before King Priam, he wove a convincing tale of betrayal and revenge.

“My lord,” Sinon said, throwing himself at Priam’s feet, “I am a Greek soldier abandoned by my own people. Odysseus falsely accused me of treachery and convinced the army to leave me behind to die.”

Sinon’s story was carefully crafted to appeal to Trojan sympathies while explaining the horse’s presence. He claimed that the Greeks had built it as an offering to Athena to ensure safe passage home, but had made it deliberately large so that the Trojans could not bring it into their city.

“The prophecy states that if the horse enters Troy, the city will be blessed with divine protection and will become invincible in future wars,” Sinon explained. “But if it is destroyed or left outside, the goddess’s wrath will fall upon Troy instead.”

Some Trojans remained skeptical, particularly Laocoon, who cried out, “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts! Whatever this thing is, I fear it even when they bring offerings!”

To demonstrate his point, Laocoon hurled his spear at the horse’s side, where it stuck quivering in the wooden flanks. For a moment, those listening carefully might have heard the sound of armor clinking from within—but just then, a terrible omen occurred that seemed to validate Sinon’s story.

The Fate of Laocoon

Two enormous sea serpents emerged from the waters and slithered up the beach toward the city. They made straight for Laocoon and his two young sons, wrapping their coils around all three and crushing them to death before the horrified eyes of the Trojan people.

To most observers, this seemed clear divine punishment for Laocoon’s disrespect toward what was apparently a sacred offering. The priest’s death silenced most remaining opposition to bringing the horse into the city.

“The gods themselves have spoken,” declared one of the Trojan elders. “Laocoon’s blasphemy has been punished, and we must not repeat his mistake.”

Even Priam, despite his years of experience and natural caution, was convinced by the apparent divine intervention. “Break down the wall,” he commanded. “We will bring this offering into our city and gain Athena’s favor for Troy.”

The Horse Enters Troy

The task of bringing the enormous horse through Troy’s gates required breaking down a section of the city wall—the very wall that had protected Troy for ten years of siege. Some citizens worried about this breach in their defenses, but the majority were caught up in the excitement of what seemed to be divine favor finally turning toward Troy.

With ropes and rollers, hundreds of Trojans worked together to drag the massive wooden horse through the gap in their wall and into the heart of their city. Children danced around it, women threw flowers, and men sang songs of victory. It was placed in the central square, near the palace, where it could be properly honored as a gift to the gods.

That night, Troy celebrated as it had not done in ten years. Wine flowed freely, and for the first time since the war began, the city’s defenders allowed themselves to believe that they had finally achieved victory. The Greeks were gone, their ships vanished over the horizon, and Troy had gained what appeared to be divine protection.

Helen, now the wife of Deiphobus, looked upon the great horse with mixed feelings. Some part of her—perhaps touched by divine insight—sensed something amiss, but she kept her suspicions to herself. She had caused enough trouble for Troy; she would not add to it with unfounded fears.

The Trap Springs

As midnight approached and the celebration died down, the exhausted Trojans finally sought their beds. Guards remained at their posts on the walls, but their vigilance was relaxed—after all, what threat could there be with the Greeks gone and the gods apparently favoring Troy?

Inside the horse, Odysseus and his companions had waited through hours of heat, cramped conditions, and the sounds of celebration around their hiding place. Finally, when the city seemed quiet, Odysseus gave the signal.

The hidden panel in the horse’s belly opened, and ropes were lowered to the ground. One by one, the Greek warriors climbed down into the heart of Troy. They were armed and ready for battle, but their first task was not combat—it was to open the city’s gates for their returning army.

While some of the hidden warriors moved to secure the gates, others began lighting signal fires to call back the Greek fleet. On Tenedos, the waiting army saw the signals and immediately set sail for Troy, their ships cutting through the dark waters with desperate speed.

The Sack of Troy

The first Trojans to discover the trick were the guards at the main gate, but by then it was too late. Greek warriors had already secured the gatehouse, and the massive doors that had protected Troy for a decade swung open to admit the returning army.

What followed was swift and brutal. The Greeks, frustrated by ten years of siege and remembering their fallen comrades, showed little mercy. Street by street, house by house, they fought their way through the city as Trojan defenders, roused from sleep and caught completely off guard, tried desperately to organize resistance.

King Priam, awakened by the sounds of battle, armed himself with weapons he had not worn in years and attempted to lead the defense of his palace. But the old king was no match for the Greek warriors who burst into his throne room. He was cut down by Neoptolemus, son of Achilles, who showed none of his father’s respect for worthy opponents.

Throughout the city, similar scenes of destruction played out. The temples that had stood for centuries were looted and burned. The palace that had housed the royal family of Troy was put to the torch. The great walls that had protected the city were breached in multiple places, ensuring that Troy could never again pose a threat to Greek interests.

The Fate of the Royal Family

The destruction of Troy’s royal family was particularly thorough. Besides Priam, most of his remaining sons were killed in the fighting. Queen Hecuba was taken as a slave, her dignity stripped away as she was forced to serve her enemies.

Deiphobus, Helen’s final Trojan husband, was killed by Menelaus himself, who had finally come to reclaim his wife. Helen, for her part, was spared—whether because Menelaus still loved her, because her divine parentage protected her, or because the gods had determined her fate differently, no one could say for certain.

The youngest members of the royal family faced particularly tragic ends. Astyanax, the infant son of the dead Hector, was thrown from Troy’s walls by the Greeks, who feared that he might one day grow up to avenge his father and rebuild Troy. The sight of the child’s death broke the hearts even of some Greek warriors, but their leaders deemed it necessary to prevent future rebellion.

Cassandra, the prophetess who had foreseen Troy’s fall but had never been believed, was claimed by Agamemnon as his prize. Her gift of prophecy, which had brought her nothing but sorrow in Troy, would ultimately lead to her death in Mycenae when she and Agamemnon were killed by his wife Clytemnestra.

The Escape of Aeneas

Not all of Troy’s defenders perished in the sack, however. Aeneas, a cousin of the royal family and one of Troy’s greatest remaining warriors, managed to escape the burning city with his father Anchises, his young son Ascanius, and a small band of followers.

According to later legends, Aeneas carried his aged father on his shoulders through the flames and smoke, leading his people to safety through passages known only to native Trojans. His escape would prove significant for the future, as his descendants would eventually found Rome, ensuring that Trojan blood would flow in the veins of those who would one day conquer Greece.

The goddess Venus, Aeneas’s divine mother, protected her son during his flight, hiding him in mist when Greek patrols came too close and guiding him to where ships waited to carry the survivors away from their ruined homeland.

The Division of Spoils

With Troy finally fallen, the Greek leaders gathered to divide the spoils of victory. The city’s treasures, accumulated over centuries of trade and prosperity, were vast. Gold, silver, precious gems, fine textiles, and works of art were distributed among the victorious armies according to rank and contribution to the victory.

But it was the human spoils that proved most controversial. Trojan women and children were enslaved and divided among the Greek leaders as prizes. Hecuba went to Odysseus, Cassandra to Agamemnon, and Andromache, Hector’s widow, to Neoptolemus.

Helen’s fate was decided by Menelaus, who had every right under Greek law to kill her for her adultery and the suffering it had caused. Yet when he saw her again—still beautiful despite the years of war—his anger wavered. Whether influenced by her divine parentage, his own remaining love, or simply war-weariness, he chose to take her back as his wife.

The Return Home

The fall of Troy marked not just the end of the war, but the beginning of new stories as the Greek heroes attempted to return to their homes. Few would find the journey easy, and many would discover that a decade of absence had changed their kingdoms as much as the war had changed them.

Agamemnon would return to Mycenae only to be murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, who had never forgiven him for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia at the war’s beginning. His death would begin a new cycle of blood and revenge that would haunt the house of Atreus for generations.

Odysseus would face ten years of wandering, encountering monsters, gods, and challenges that would test his cunning and endurance to their limits. His epic journey home would become as famous as the war itself, demonstrating that even victory in war does not guarantee peace.

Other Greek heroes faced their own fates. Some, like Diomedes, returned home to find their thrones usurped. Others, like Idomeneus, found their kingdoms changed beyond recognition. A few, deemed too dangerous by the gods or too tainted by the brutality of war, were forbidden to return home at all.

The Legacy of Troy’s Fall

The destruction of Troy marked the end of an era in the ancient world. A city that had stood for centuries, a center of trade and culture that had connected East and West, was reduced to rubble and ash. The Trojan War had begun with the abduction of one woman, but it had escalated into a conflict that reshaped the political landscape of the entire region.

Yet from Troy’s ashes would arise new stories and new hopes. The scattered survivors would carry Trojan culture to new lands, eventually contributing to the founding of Rome. The lessons learned from the war—about honor and pride, about the costs of conflict, about the complex relationship between mortals and gods—would be preserved in epic poetry that would inspire future generations.

The tale of the Trojan Horse became one of the most famous stories in all of literature, a reminder that brain can triumph over brawn, that the mightiest fortress can fall to cunning rather than force. It demonstrated that in war, as in life, victory often goes not to the strongest or most virtuous, but to those who can adapt their strategies to changing circumstances.

Most importantly, the fall of Troy served as a meditation on the nature of fate and free will. The war had been decreed by the gods, set in motion by divine quarrels and mortal choices, yet it had played out through the actions of individuals who believed they were making free decisions. Whether the war could have been prevented, whether Troy’s fall was inevitable, whether the suffering it caused was justified—these questions would be debated by philosophers and poets for centuries to come.

In the end, the fall of Troy stands as one of mythology’s greatest stories because it encompasses so many fundamental human experiences: love and loss, honor and betrayal, courage and fear, wisdom and folly. It reminds us that even the mightiest cities can fall, that even the greatest heroes are mortal, and that the consequences of our choices often extend far beyond what we can foresee. The wooden horse that brought down Troy’s walls became a symbol not just of clever strategy, but of how the most destructive forces often come disguised as gifts, and how our greatest victories can contain the seeds of our greatest tragedies.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus