Pygmalion and Galatea

Story by: Greek Mythology

Source: Ovid's Metamorphoses

Pygmalion and Galatea

On the island of Cyprus, sacred to Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty, there once lived a gifted sculptor named Pygmalion. His hands could coax such lifelike forms from marble and ivory that people often joked his statues might step from their pedestals and walk among the living. Despite his artistic success and the admiration of his fellow citizens, Pygmalion lived a solitary life, finding more joy in his workshop than in the company of others.

It wasn’t that Pygmalion disliked people. Rather, he had grown disillusioned with the women of Cyprus, whom he found lacking in the virtues he most admired. Some versions of the myth suggest he had witnessed such depravity among the Propoetides—women who denied Aphrodite’s divinity and were punished by being turned to stone after losing all sense of shame—that he had sworn off romantic relationships entirely. Others imply that his standards were simply too exacting, that he sought a perfection in others that could not exist in flawed human beings.

Whatever the reason, Pygmalion channeled his loneliness and idealism into his art. He poured all his passion, all his dreams of feminine perfection, into a single work—a statue carved from flawless ivory, representing a woman of such extraordinary beauty and grace that no living person could match her.

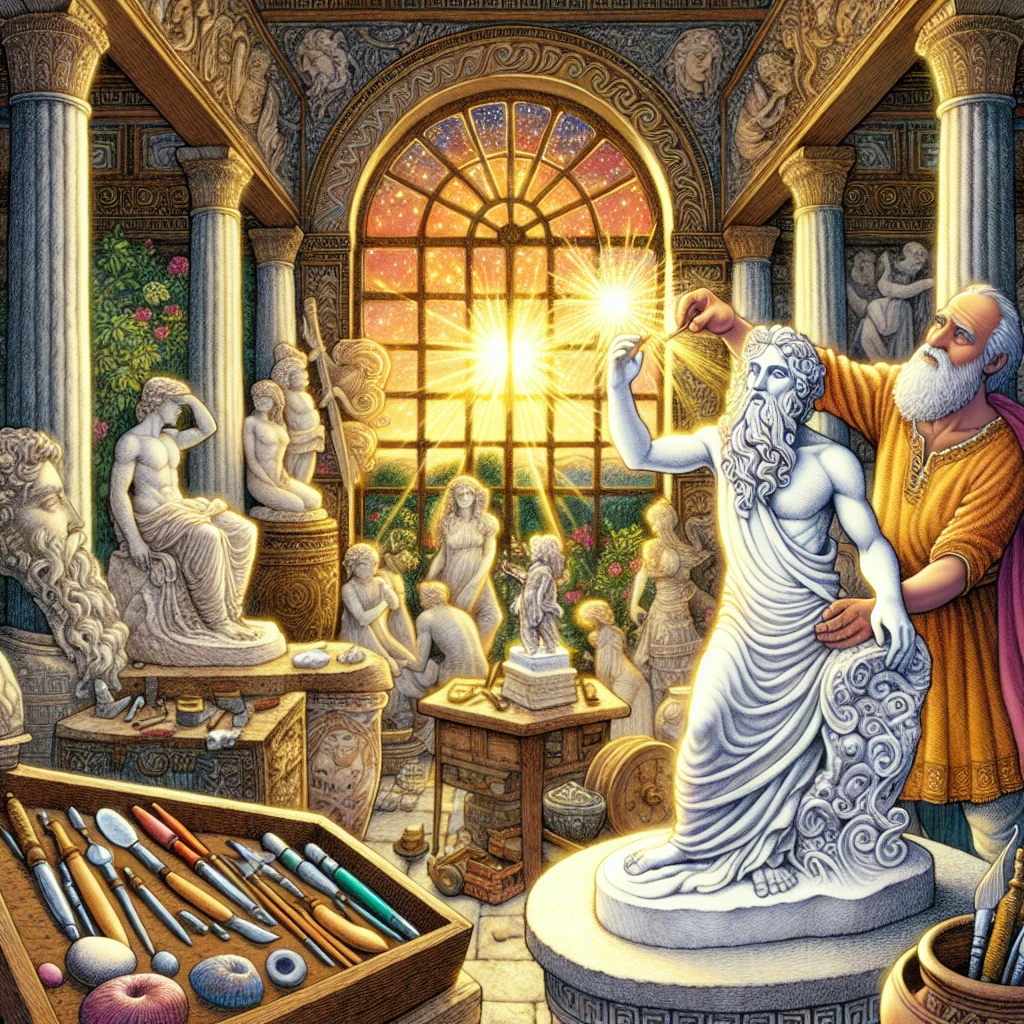

Day after day, Pygmalion worked on his masterpiece. His chisel moved with unprecedented precision, guided not just by skill but by something deeper—a vision of ideal beauty that seemed to come from beyond himself. He carved delicate features that somehow managed to convey both innocence and wisdom. He shaped a form that was the perfect balance of strength and softness. He polished the ivory until it gleamed like skin kissed by the sun, with a warmth that belied its cold material.

When the statue was complete, Pygmalion stood back and was astonished by what he had created. The figure seemed almost to breathe. Her lips appeared soft enough to speak, her eyes so expressively carved that they seemed ready to blink. The sculptor had outdone himself, creating not just a representation of the feminine ideal but a work that captured something of the divine spark itself.

“If only you were real,” he whispered to the statue, reaching out to touch her cool cheek with reverent fingers.

In the days that followed, Pygmalion’s behavior grew increasingly unusual. He began to treat the statue as if she were alive. He named her Galatea, meaning “she who is milk-white,” a reference to the gleaming ivory from which she was carved. He brought her gifts—flowers that he placed in her unmoving hands, jewels that he draped around her neck, fine fabrics that he wrapped around her shoulders. He spoke to her throughout the day, telling her about his work, his thoughts, the happenings in the city.

At night, he would carefully lay her on a couch covered with purple blankets and cushions stuffed with down, as if preparing a resting place for a beloved. Sometimes he would lie beside her, imagining that the cold ivory had somehow grown warm, that the chest he had so painstakingly carved now rose and fell with breath.

Pygmalion knew, in the rational part of his mind, that his behavior was strange, perhaps even verging on madness. But he could not help himself. He had fallen deeply in love with his own creation—not out of narcissism, but because he had poured into Galatea everything he had ever hoped to find in a companion. She was not just beautiful but seemed to embody kindness, modesty, intelligence, and grace—all the virtues he had sought in vain among living women.

The citizens of Cyprus began to whisper about the sculptor’s strange obsession. Some mocked him behind his back, while others felt pity for a man so lonely that he had resorted to treating a statue as his beloved. Pygmalion, aware of these whispers but beyond caring about public opinion, continued his unusual courtship of the unresponsive Galatea.

It happened that the festival of Aphrodite, the most important religious celebration on Cyprus, was approaching. Despite his eccentric behavior, Pygmalion was still a pious man who honored the gods, particularly Aphrodite, whose domain of love and beauty was so connected to his own work as an artist. He went to her temple, bringing the richest offerings he could afford—fat cattle for sacrifice, sweet-smelling incense, and golden ornaments to adorn the goddess’s shrine.

Standing before the altar, the flames of sacrifice rising around him, Pygmalion made a prayer that he dared not speak aloud, even in the sacred precincts of the temple. “Great Aphrodite,” he thought, his heart pounding with mingled hope and shame, “if it is within your power, if it would not offend the natural order too greatly… give me a wife like my Galatea.”

He couldn’t bring himself to ask directly for the statue to be brought to life, for such a request seemed too presumptuous, too close to challenging the gods’ exclusive power over life and death. But Aphrodite, who could see into the hearts of mortals and understand their deepest desires, knew what Pygmalion truly wished for.

As the sculptor made his way home from the temple, a strange anticipation filled him. The air seemed charged with possibility, the ordinary streets of the city somehow more vibrant and alive than usual. He hurried his steps, eager to return to his silent companion, to tell her about the festival and his prayers, as had become his custom.

Entering his workshop, Pygmalion approached the pedestal where Galatea stood. The last rays of the setting sun streamed through the windows, bathing the statue in golden light that made the ivory seem to glow from within. He reached out, as he had countless times before, to touch her hand—a gesture that had become a ritual greeting between creator and creation.

But this time, something extraordinary happened. As his fingers met the ivory, he felt not the cool hardness he expected, but a yielding softness. Beneath his touch, the statue’s hand seemed to warm, the texture transforming from smooth, polished ivory to the subtle irregularities of human skin.

Pygmalion drew back in shock, wondering if his mind had finally broken under the strain of his impossible love. But as he watched in wonder and terror, the transformation continued. A flush of pink spread across the statue’s cheeks. The perfectly carved chest began to rise and fall with actual breath. The lips, which he had shaped with such care, parted slightly as if drawing in air for the first time.

And then the eyes—those eyes into which he had carved such expressiveness—blinked. They focused on him with a gaze that was no longer the fixed stare of statuary but the living, shifting attention of a conscious being.

“Galatea?” Pygmalion whispered, his voice breaking with emotion.

The statue—no, the woman—smiled tentatively. She took a small, experimental step forward, leaving the pedestal that had been her home since her creation. Her movements were hesitant at first, like those of a child learning to walk, but with each passing moment they became more fluid, more natural.

“Pygmalion,” she said, her voice soft and musical, speaking the name she had heard so often during the sculptor’s one-sided conversations with his creation. The sound of his name on her lips—real lips now, warm and living—nearly brought the artist to his knees.

It was clear that Aphrodite had heard his unspoken prayer and, moved perhaps by the purity of his love or simply feeling generous during her festival, had granted his deepest wish. The goddess had breathed life into ivory, transforming Galatea from a cold artistic representation into a warm, living woman with a soul of her own.

What followed this miracle was something like a courtship, though one unlike any other in history. Pygmalion, who had imagined a personality for Galatea during all those months of speaking to an unresponsive statue, now had the strange experience of discovering who she truly was. In some ways, she matched his imaginings perfectly—kind, gentle, intelligent. In others, she surprised him with thoughts and preferences he could never have anticipated.

Galatea, for her part, had to learn what it meant to be human. Though she came to life with the ability to speak and understand language—a gift from Aphrodite, presumably—she knew nothing of the world beyond what she had heard from Pygmalion’s daily monologues. Every experience was new to her—the taste of food, the feeling of the sun on her skin, the sound of music, the scent of flowers. Her delight in these discoveries brought fresh joy to Pygmalion, allowing him to see the familiar world through new eyes.

The citizens of Cyprus, who had mockingly pitied the sculptor for his strange obsession, were astounded by the beautiful, somewhat otherworldly woman who now accompanied him everywhere. Most assumed she was a foreign bride he had somehow met and married in secret. Only a few, noting her uncanny resemblance to the statue that had vanished from Pygmalion’s workshop, guessed at something more miraculous.

Pygmalion and Galatea were formally married in a ceremony blessed by Aphrodite herself, who was said to have attended invisibly, pleased with this unusual love story she had helped to create. The couple lived a long and happy life together, blessed with at least one child—a daughter named Paphos, after whom the city sacred to Aphrodite was later named. Some versions of the myth also mention a son, Metharme.

The story of Pygmalion and Galatea has fascinated people for thousands of years, not just as a romantic fantasy but as an exploration of profound themes about art, love, and the nature of creation itself.

At its most basic level, the myth speaks to the ancient Greek belief in the transformative power of the gods. Aphrodite’s ability to bring the statue to life reinforces her domain over love in all its forms, including the love between creator and creation. It also reflects the Greek understanding that the divine and human realms were not entirely separate—that gods could and did intervene in mortal affairs, sometimes granting extraordinary boons to those who properly honored them.

On a deeper level, the myth explores the relationship between art and reality. Pygmalion’s statue is so perfect, so lifelike, that it transcends the boundary between representation and the thing represented. This idea fascinated the Greeks, who valued art that could convincingly mimic nature. The story suggests that the highest achievement of art is not just to imitate life but to somehow capture its essence so completely that the boundary between art and life dissolves.

The myth also raises interesting questions about the nature of love. Pygmalion falls in love not with a real woman, with all the complexities and flaws that entails, but with his own idealized creation. This could be read as a critique of those who love not actual people but their own projections or fantasies. Yet the myth doesn’t condemn Pygmalion for this. Instead, it rewards him, suggesting perhaps that there is something pure about loving an ideal, even if that ideal exists only in art or imagination.

There’s an ambiguity, too, in Galatea’s transformation. Does she retain any memory or consciousness from her time as a statue? Does she have true autonomy, or is she in some sense still Pygmalion’s creation, shaped by his desires? The myth doesn’t answer these questions, leaving room for different interpretations about the nature of Galatea’s new existence and what it means for her relationship with her creator-turned-husband.

For philosophers and psychologists, the story raises fascinating questions about projection and narcissism. Is Pygmalion in love with Galatea, or with his own artistic achievement? Is he loving another or merely an extension of himself? The myth can be read either as a celebration of the creative power of love or as a cautionary tale about the dangers of loving one’s own creation too much.

The cultural impact of the Pygmalion myth has been enormous, inspiring countless retellings and variations across different media. George Bernard Shaw’s play “Pygmalion” (later adapted into the musical “My Fair Lady”) uses the myth as a starting point for exploring how language and education can transform a person’s social identity. Contemporary discussions about artificial intelligence and robotics often reference the myth when questioning whether humans could develop romantic feelings for the non-human entities they create.

For artists, the story has special resonance. Every creative person knows something of Pygmalion’s experience—the sense that one’s creation takes on a life of its own, developing in ways the creator might not have consciously intended. Writers speak of characters who seem to make their own decisions, musicians of melodies that appear to write themselves, painters of images that emerge from the canvas as if by their own will. The myth speaks to this mysterious aspect of the creative process, the feeling that art exists somewhere between conscious intention and something more elusive, perhaps even divine.

There’s also a psychological truth in the story about the power of love and belief to transform. While we can’t literally bring statues to life, we do know that seeing potential in others—believing in them, loving them for what they might become—can help them grow and change. In this sense, every lover is a kind of Pygmalion, and every beloved has something of Galatea in them, shaped in part by the perceptions and expectations of those who love them.

Finally, the myth touches on the universal human longing for connection so deep that it transcends ordinary boundaries. Pygmalion’s love for Galatea is impossible by any rational standard, yet it moves even a goddess to compassion. There’s something profoundly hopeful in this idea—that love, at its most authentic and passionate, might be powerful enough to transform reality itself, to breathe life into what was lifeless, to create connection where none seemed possible.

In a world increasingly mediated by technology and virtual experiences, where the line between the real and the artificial grows ever more blurred, the story of Pygmalion and Galatea continues to resonate. It reminds us of our deep human desire for authentic connection, even as it raises unsettling questions about the nature of that authenticity. It celebrates the transformative power of both art and love, while acknowledging the complex, sometimes troubling relationship between creator and creation.

And perhaps most importantly, it offers a vision of a world where the boundaries we take for granted—between art and life, between human and divine, between what is and what might be—are more permeable than we imagine. In that permeability lies both danger and possibility, both the potential for delusion and the hope for genuine transformation. Like all great myths, the story of Pygmalion and Galatea doesn’t resolve these tensions but holds them in perfect balance, leaving us to wonder at their implications for our own lives and loves.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus