Oedipus Rex

Story by: Sophocles

Source: Greek Mythology

In the ancient city of Thebes, where seven gates protected its walls and the river Ismenus wound through fertile fields, there unfolded one of the most tragic and powerful stories in all of Greek mythology. It is the tale of a man who sought to escape his destiny, only to run headlong into it; a story of kings and prophecies, of riddles and revelations, and of how the very actions we take to avoid our fate often serve to fulfill it.

The Prophecy of Doom

The story begins before Oedipus was even born, in the palace of King Laius and Queen Jocasta of Thebes. Laius, troubled by his inability to father an heir, traveled to the Oracle at Delphi to seek guidance from Apollo’s priestess. The response he received was not the blessing he had hoped for, but a warning that chilled his heart.

“Laius of Thebes,” the Oracle proclaimed, her voice echoing through the sacred chamber, “you shall have a son, but know this—that child is destined to kill his father and marry his mother. Through him, the curse upon your house shall be fulfilled, and great suffering shall come to pass.”

Horrified by this prophecy, Laius returned to Thebes with a heavy heart. When Jocasta did indeed bear him a son, the king was faced with a terrible choice. The infant was healthy and strong, with bright eyes that seemed to hold great intelligence, but the Oracle’s words haunted Laius day and night.

“We cannot let this child live,” Laius told his queen, though the words tasted like poison in his mouth. “The Oracle’s prophecies are never wrong. If we keep him, we doom ourselves and our kingdom.”

Jocasta wept bitterly, but she understood the weight of divine prophecy. With hearts breaking, they gave the infant to a trusted servant with orders to abandon him on Mount Cithaeron, where wild beasts would ensure he could never fulfill the terrible prophecy. To prevent the child from crawling to safety, they pierced his ankles with a brooch and bound them together.

But fate, as it so often does, had other plans.

The Shepherd’s Mercy

The servant, upon reaching the desolate slopes of Mount Cithaeron, could not bring himself to leave the innocent child to die. Instead, he encountered a shepherd from Corinth who took pity on the infant. This shepherd, moved by compassion, carried the baby to his own city and presented him to King Polybus and Queen Merope, who had long prayed for a child of their own.

The royal couple gladly adopted the infant, healing his injured ankles and naming him Oedipus—meaning “swollen foot”—after the wounds he had suffered. They raised him as their own son, never telling him of his true origins, and Oedipus grew up believing himself to be a prince of Corinth.

Oedipus matured into a man of exceptional intelligence and courage, beloved by his adoptive parents and respected throughout Corinth. He was handsome and athletic, quick to learn and quicker still to act when he believed justice was at stake. Yet despite his privileged upbringing, he was sometimes troubled by comments from others about his appearance, which some claimed differed from that of his supposed parents.

The Oracle’s Revelation

When Oedipus reached manhood, these doubts drove him to seek answers at the Oracle of Delphi. He approached the sacred site with questions about his parentage, hoping to put his uncertainties to rest. Instead, the Oracle delivered a prophecy that horrified him—the same prophecy that had been given to Laius years before.

“Oedipus,” the priestess intoned, “you are destined to kill your father and marry your mother. Your children shall be your siblings, and great tragedy shall follow in your wake.”

Terrified by this pronouncement and believing Polybus and Merope to be his real parents, Oedipus made a fateful decision. Rather than return to Corinth and risk fulfilling the prophecy, he would exile himself and wander the world. In this way, he believed, he could protect those he loved from the fate the Oracle had decreed.

With a heavy heart but firm resolve, Oedipus set out from Delphi, taking the road that led away from Corinth. He had no destination in mind except distance from those he believed to be his parents. It was on this road that fate began to weave its inexorable web.

The Crossroads Encounter

At a place where three roads met—a crossroads that would become famous in the annals of tragedy—Oedipus encountered a small party of travelers. In the lead chariot rode an older man of obvious nobility, flanked by several attendants. The road was narrow, and neither party was inclined to yield the right of way.

“Stand aside, young man!” called the herald accompanying the noble’s party. “Make way for King Laius of Thebes!”

But Oedipus, now in self-imposed exile and in no mood to defer to anyone, refused to step aside. “I yield the road to no man,” he declared, his voice carrying the authority of one raised as a prince. “There is room for both parties to pass if courtesy is shown on both sides.”

The situation escalated quickly. The herald struck Oedipus with his staff, and King Laius himself, in a rage at this perceived insolence, drove his chariot forward, the wheels striking Oedipus and knocking him to the ground. In that moment, the young man’s temper—always his greatest weakness—flared beyond control.

Rising to his feet, Oedipus seized a weapon and struck down both the herald and the king. The remaining attendants fled in terror, leaving only one survivor to carry word back to Thebes that their king had been killed by a stranger at the crossroads.

Oedipus, shaken by what he had done but believing it to be justified self-defense, continued on his journey. He had no idea that he had just fulfilled the first part of the Oracle’s prophecy—he had killed his father. Laius was indeed his true father, the very man who had ordered his death as an infant and set in motion the chain of events that led to this tragic encounter.

The Sphinx and the Riddle

Oedipus’s path led him to the outskirts of Thebes, a city in the grip of terror. For months, a creature called the Sphinx had positioned herself on a rocky outcrop outside the city gates, posing a riddle to all who wished to enter. Those who answered incorrectly were devoured on the spot, while those who refused to answer were torn apart by her claws.

The Sphinx was a fearsome creature with the head of a woman, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle. Her human face was beautiful but cold, her eyes holding the intelligence of something far more than mortal. She had been sent by the gods as a punishment upon Thebes, though the exact nature of the city’s offense was debated among its terrified citizens.

As Oedipus approached the city, he could see the bleached bones of previous travelers scattered around the creature’s perch. But rather than turn away or seek another route, his intellectual curiosity was aroused. Here was a challenge worthy of his intelligence, a puzzle that might restore his sense of purpose after the traumatic events at the crossroads.

“Hold, traveler,” the Sphinx called as he drew near, her voice melodious but with an underlying threat. “Would you enter Thebes? Then answer me this riddle: What creature walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at midday, and three legs in the evening?”

Oedipus considered the riddle carefully, his mind working through the metaphors and possibilities. Many before him had offered literal answers—various animals or mythical creatures—only to meet their doom. But Oedipus recognized that the riddle spoke not of any single creature, but of the stages of life itself.

“The answer is man,” he replied confidently. “In the morning of life, he crawls on hands and knees as a baby. In the midday of life, he walks upright on two legs as an adult. And in the evening of life, he uses a walking stick as a third leg in his old age.”

The Sphinx shrieked in fury and amazement—never before had anyone answered correctly. According to the divine decree that bound her, she was now compelled to destroy herself. With a final cry of rage, she hurled herself from the rocky precipice to her death below.

The Crown of Thebes

The people of Thebes, freed from the terror of the Sphinx, welcomed Oedipus as their savior. The city had been without a king since the death of Laius, and the royal council, impressed by Oedipus’s wisdom and courage, offered him the throne. As was customary, this honor came with marriage to the widowed queen, Jocasta.

Oedipus, believing himself safe from the Oracle’s prophecy as long as he remained away from Corinth, accepted both the crown and the marriage. Jocasta, still grieving for her lost husband but needing the security that a strong king could provide, agreed to the union. Neither recognized the other—Oedipus had been only an infant when Jocasta last saw him, and she believed him long dead.

“The gods have sent you to us in our darkest hour,” Jocasta said during their wedding ceremony, her words more prophetic than she could possibly have known. “May your reign bring peace and prosperity to Thebes.”

For many years, it seemed as though her blessing would prove true. Oedipus ruled wisely and well, proving himself an able administrator and a just judge. He and Jocasta were blessed with four children: two sons, Eteocles and Polynices, and two daughters, Antigone and Ismene. The royal family was respected and beloved, and Thebes flourished under Oedipus’s rule.

But the Oracle’s prophecy was not yet complete, and the gods had not finished with the house of Laius.

The Plague of Thebes

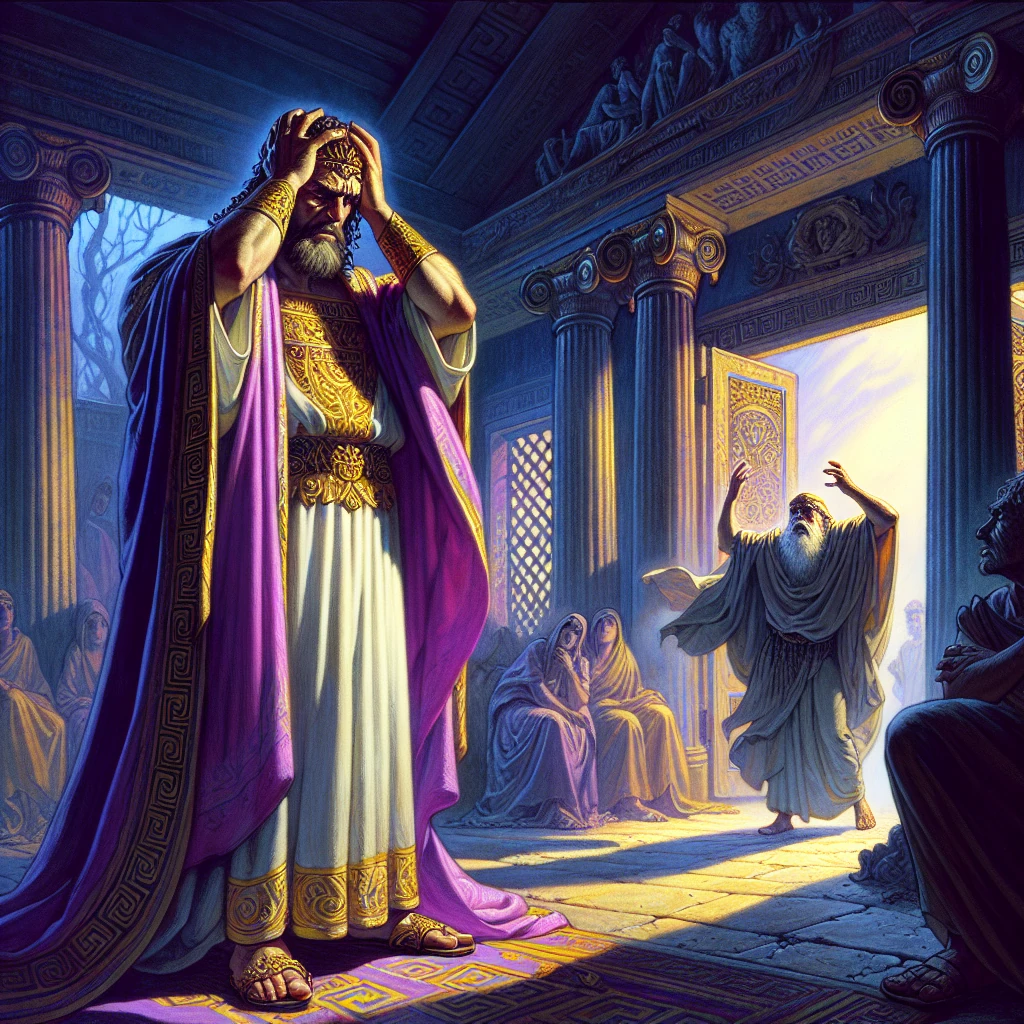

Years into Oedipus’s reign, a terrible plague descended upon Thebes. Crops withered in the fields, livestock died, and women miscarried or bore stillborn children. The city’s population began to decline as disease and death stalked every household. The people, desperate for relief, gathered in the palace courtyard to petition their king for action.

“Great Oedipus,” pleaded the priest who spoke for the crowd, “you who saved us from the Sphinx, surely you can find a way to lift this curse from our city. The gods have sent this plague for a reason, and only by discovering and addressing that reason can we hope for relief.”

Moved by his people’s suffering and determined to prove worthy of their faith in him, Oedipus had already sent his brother-in-law Creon to consult the Oracle at Delphi. When Creon returned, his news was both hopeful and ominous.

“The Oracle declares that the plague will end when the murderer of King Laius is found and punished,” Creon announced to the assembled court. “The killer walks among us still, unpunished for his crime, and his presence pollutes the city.”

Oedipus, still unaware of his own guilt, immediately decreed that the murderer would be found and brought to justice. “I call upon all citizens of Thebes to aid in this search,” he declared. “Let no one harbor this criminal, and let no family tie or friendship prevent the truth from coming to light. I swear by all the gods that justice will be done.”

The Blind Prophet’s Warning

To aid in the investigation, Oedipus summoned Tiresias, the blind prophet of Thebes, whose gift of sight into divine matters was legendary throughout Greece. Tiresias was ancient beyond measure, his sightless eyes holding wisdom accumulated over many generations of mortal lives.

“Great Tiresias,” Oedipus said when the prophet arrived at the palace, “you who see what others cannot, help us identify the killer of King Laius. The Oracle has said that only by punishing this murderer can we lift the plague from our city.”

But Tiresias, upon hearing the request, grew visibly troubled. His supernatural sight allowed him to perceive truths that mortal eyes could not see, and he understood exactly who stood before him. The knowledge filled him with sorrow for what must come to pass.

“My king,” Tiresias said carefully, “sometimes knowledge brings more pain than ignorance. Let this matter rest. Send me away, and seek your answers elsewhere.”

His reluctance only inflamed Oedipus’s curiosity and determination. “You know something,” the king accused. “Are you protecting the killer? Do you perhaps have some involvement in the crime yourself?”

These accusations stung the ancient prophet. “You accuse me of murder?” Tiresias replied, his voice rising with righteous anger. “You who seek the killer of Laius—the killer is yourself! You are the curse upon this city, you are the pollution that brings the plague!”

The Terrible Truth Emerges

Oedipus reacted with fury to what he perceived as a mad accusation. “You speak in riddles and lies!” he shouted. “What could I possibly have to do with the death of Laius? I never even met the man!”

But Tiresias, now committed to revealing the truth despite its terrible consequences, continued his prophecy. “You will discover that you are not who you believe yourself to be. The parents you think you know are not your parents. The wife you love is not who she seems to you. Before this day ends, the truth will be revealed, and you will wish that you had remained ignorant.”

As the prophet’s words sank in, a cold dread began to creep into Oedipus’s heart. He had spent years suppressing memories of the encounter at the crossroads, telling himself that it had been justified self-defense against bandits. But now, details began to resurface with uncomfortable clarity.

Jocasta, witnessing this exchange and growing increasingly alarmed, tried to dismiss Tiresias’s words. “Pay no attention to prophecies and oracles,” she urged her husband. “I had a prophecy once that told me my first child would kill his father and marry his mother. But that child died as an infant, and Laius was killed by bandits at a crossroads, not by any son of mine.”

Her words, meant to comfort, had the opposite effect. “A crossroads?” Oedipus asked, his voice barely a whisper. “Tell me everything about Laius’s death—when it happened, where, how many were in his party.”

As Jocasta described the circumstances of her first husband’s death, each detail matched perfectly with Oedipus’s memories of that fateful day. The location, the time, the description of the king’s appearance—everything confirmed his growing fear that he had indeed killed his own father.

“Send for the shepherd,” Oedipus commanded, his voice hollow with dread. “The one who survived Laius’s death. And find the man who brought me as an infant to the court of Corinth. I must know the truth, whatever the cost.”

The Final Revelation

When the messengers brought the Corinthian shepherd to the palace, the final pieces of the tragic puzzle fell into place. Under questioning, the old man revealed that he had indeed received an infant from another shepherd on Mount Cithaeron—an infant with wounded ankles who had been abandoned to die.

“The child was given to me by a servant of King Laius,” the shepherd admitted reluctantly. “He said the baby had been condemned to death because of some prophecy. I took pity on the innocent child and brought him to Corinth, where King Polybus and Queen Merope raised him as their own.”

Jocasta, realizing the horrible truth before her husband did, fled from the chamber with a cry of anguish. Oedipus, driven by a compulsion to know everything despite the mounting evidence of his guilt, pressed for more details.

“The child’s name,” he demanded. “What was he called?”

“His ankles were pierced and swollen,” the shepherd replied. “We called him Oedipus—‘swollen foot.’”

The truth struck Oedipus like a physical blow. He was indeed the child of Laius and Jocasta, condemned to death as an infant because of the Oracle’s prophecy. He had killed his father at the crossroads, not knowing who he was. He had married his mother and fathered children who were also his siblings. Every action he had taken to avoid his fate had instead led him directly to it.

The Tragic Conclusion

Overwhelmed by the magnitude of his crimes and the terrible irony of his situation, Oedipus rushed to find Jocasta. He discovered her in their bedchamber, dead by her own hand, having hanged herself with the cord from her robe rather than face the shame of what their relationship had been.

In his grief and self-loathing, Oedipus took the golden brooches from Jocasta’s dress and drove their pins into his own eyes, blinding himself. “These eyes have seen too much,” he cried out in anguish. “They have looked upon things that should never have been seen. Better that they see nothing at all than witness the pollution I have brought into the world.”

Blind and broken, Oedipus abdicated his throne and begged to be exiled from Thebes. His children—Antigone, Ismene, Eteocles, and Polynices—were left to deal with the aftermath of the revelation, while the city struggled to cleanse itself of the pollution that the king’s unwitting crimes had brought upon it.

“I am the most cursed of men,” Oedipus declared as he prepared to leave the city he had once saved. “Born to commit crimes I never intended, destined to fulfill a prophecy I spent my life trying to escape. Let my story serve as a warning—that mortals cannot escape the will of the gods, and that sometimes our very efforts to avoid our fate serve only to ensure it comes to pass.”

Thus ended the reign of Oedipus Rex, one of the most tragic figures in all of mythology. His story has resonated through the ages as a powerful exploration of fate versus free will, the dangers of pride and the pursuit of forbidden knowledge, and the complex relationship between intention and consequence. In seeking to escape his destiny, Oedipus ensured its fulfillment; in trying to save those he loved, he brought about their destruction. The tragedy of Oedipus Rex remains one of the most psychologically complex and emotionally powerful stories ever told, a timeless examination of the human condition and the mysterious workings of divine justice.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus