Atalanta and the Golden Apples

Story by: Ovid and Various Greek Sources

Source: Greek Mythology

In the ancient forests of Arcadia, where wild boars roamed through dense thickets and deer bounded across sun-dappled clearings, there lived a huntress whose speed and skill were legendary throughout Greece. Her name was Atalanta, and she was as beautiful as she was swift, as independent as she was accomplished. Yet her story would become one of the most complex tales in Greek mythology—a narrative that explores the tensions between love and freedom, tradition and independence, and the price of defying both mortal expectations and divine will.

The Abandoned Child

Atalanta’s story began with abandonment and divine intervention. She was born to King Iasus of Arcadia, a ruler who had desperately hoped for a son to inherit his throne and continue his lineage. When his wife bore him a daughter instead, his disappointment was so great that he ordered the infant to be exposed on Mount Parthenium, left to die of exposure or become food for wild beasts.

“A daughter cannot defend the kingdom or lead armies,” Iasus declared coldly, turning away from the child he refused to acknowledge. “Let the gods decide her fate. If she is meant to live, they will provide for her.”

But the gods, particularly Artemis, goddess of the hunt and protector of young maidens, had other plans for the infant. As the baby’s cries echoed through the mountainous wilderness, they attracted not predators seeking easy prey, but a she-bear who had recently lost her own cubs.

The great bear, her maternal instincts still strong, took pity on the human child. She carried the infant to her den, where she nursed and protected her as if she were one of her own cubs. Under the bear’s care, Atalanta grew strong and hardy, learning to survive in the wild from her earliest days.

Raised by Hunters

When Atalanta was several years old, she was discovered by a group of hunters who were amazed to find a human child living wild in the mountains. These men, followers of Artemis who lived simple lives in harmony with nature, took the girl into their community and became her teachers and protectors.

“She has been blessed by Artemis,” declared Clymene, an elderly hunter who served as the group’s leader. “Look how fearlessly she moves among the wild creatures, how naturally she understands the ways of the forest. The goddess has marked her for a special purpose.”

Under the hunters’ guidance, Atalanta learned skills that would make her famous throughout Greece. She mastered the bow and arrow, becoming so accurate that she could split an arrow in flight or bring down a bird on the wing from incredible distances. She learned to track prey through the densest undergrowth, to move silently through forests, and to read the signs that told of weather changes or approaching danger.

But perhaps most remarkably, she developed a speed that was supernatural in its swiftness. When she ran, she seemed to fly across the ground, her feet barely touching the earth. Some said this speed was a gift from Artemis; others believed it came from her early upbringing among the wild creatures of the mountains.

The Devotee of Artemis

As Atalanta grew to womanhood, she dedicated herself completely to Artemis, taking the same vows of chastity that the goddess herself maintained. She had no interest in marriage or the domestic life that was expected of women in ancient Greece. Her world was the forest, her companions were her fellow hunters, and her purpose was the pursuit of excellence in all the skills Artemis valued.

“I have no need of a husband,” Atalanta would say when well-meaning hunters suggested she might someday want to settle down. “Artemis provides all I need, and in return, I offer her my complete devotion. What could marriage offer me that I do not already possess?”

Her beauty was renowned throughout the region—tall and athletic, with hair that gleamed like burnished gold and eyes that sparkled with intelligence and determination. Yet she showed no interest in the many suitors who began to seek her out as her fame spread.

Word of the remarkable huntress reached far beyond Arcadia. Stories told of her incredible speed, her unmatched skill with the bow, and her beauty that combined feminine grace with athletic power. Young men from across Greece began to make pilgrimages to the forests where she lived, hoping to win her favor.

The Calydonian Boar Hunt

Atalanta’s reputation as a huntress was cemented when she participated in one of the most famous hunting expeditions in Greek mythology—the Calydonian Boar Hunt. King Oeneus of Calydon had offended Artemis by failing to include her in his harvest sacrifices, and the goddess had sent a monstrous boar to ravage his lands.

This was no ordinary boar, but a creature of supernatural size and ferocity, with tusks like spears and hide tough enough to turn aside bronze weapons. It had laid waste to crops, destroyed villages, and killed anyone brave enough to hunt it. Finally, Oeneus’s son Meleager organized a great hunt, calling upon the greatest heroes of Greece to help slay the beast.

When Atalanta arrived to join the hunt, many of the heroes objected to including a woman in such a dangerous endeavor. Theseus, Jason, and other legendary figures had come expecting a hunt among equals, not a mixed company.

“This is no place for a woman,” declared Ancaeus, one of the Argonauts. “She will only be a distraction and a liability. Send her home before she gets herself or others killed.”

But Meleager, who had heard tales of Atalanta’s prowess and was perhaps already smitten with her beauty, insisted that she be allowed to participate. “If she wishes to face the same dangers we do, she should have that right,” he argued. “Let her prove herself worthy, or let the boar prove her unworthy.”

During the hunt itself, Atalanta was the first to wound the great boar, her arrow finding its mark when others had failed to penetrate the creature’s hide. Though Meleager ultimately delivered the killing blow, he awarded the boar’s pelt to Atalanta in recognition of her crucial contribution.

This honor, however, led to conflict among the hunters. Meleager’s uncles, Plexippus and Toxeus, resented seeing the prize go to a woman and attempted to take it from her by force. When Meleager defended Atalanta’s right to the trophy, the dispute escalated into violence that ultimately cost Meleager his life and brought tragedy to the house of Calydon.

Recognition and Reunion

The fame Atalanta gained from the Calydonian Boar Hunt spread throughout Greece and eventually reached the ears of King Iasus, her father who had ordered her exposure as an infant. Realizing that this celebrated huntress was the daughter he had rejected, Iasus sent messengers to find her and bring her home.

When the messengers arrived in the forest where Atalanta lived, their words stirred complex emotions in the young woman. “Your father, King Iasus of Arcadia, acknowledges you as his daughter and heir,” their leader announced. “He commands your return to take your rightful place in his household and eventually inherit his throne.”

Atalanta’s first impulse was to refuse. The man who had left her to die as an infant now wanted to claim her when her fame could bring honor to his name? The hypocrisy was stark, and her loyalty was to Artemis and the hunters who had actually raised her.

But her companions urged her to consider the opportunity. “You could do much good as a queen,” Clymene pointed out. “Think of how you could protect the forests and the creatures Artemis loves. Think of the example you could set for other women who wish to live independently.”

After much contemplation, Atalanta agreed to return to her father’s court, but with conditions. She would not abandon her devotion to Artemis, she would not be forced into an unwanted marriage, and she would continue to live according to her own principles rather than traditional expectations for royal women.

The Marriage Challenge

King Iasus welcomed his daughter with great ceremony, proclaiming her his heir and establishing her in the palace with all the honors due to a princess. However, he soon made it clear that despite her proven abilities and independence, he expected her to marry and provide him with grandsons to continue the royal line.

“You are my daughter and my heir,” Iasus told her during one of their first conversations, “but you must think of the future of our kingdom. A woman cannot rule alone—she needs a husband to provide strength and counsel, and she must bear sons to inherit after her.”

This expectation conflicted directly with Atalanta’s vows to Artemis and her own desires for independence. She had no intention of marrying anyone, but she also understood that outright refusal might lead to confrontation with her father or even forced marriage to someone of his choosing.

Instead, she devised a clever solution that would honor her commitment to Artemis while appearing to give suitors a fair chance. “I will marry,” she announced to her father and his court, “but only to a man who can defeat me in a foot race. Any man who wishes to compete for my hand may do so, but he must understand the stakes. If he wins, I will marry him willingly. If he loses, he forfeits his life.”

The terms were harsh, but Atalanta was confident in her supernatural speed. She had never met anyone who could match her swiftness, and she believed that the deadly consequences would deter all but the most foolishly confident suitors.

King Iasus, pleased that his daughter had agreed to marry and confident that some worthy hero would eventually succeed, approved the challenge. Word spread throughout Greece that Princess Atalanta would race any suitor for her hand, with marriage as the prize for victory and death as the penalty for defeat.

The Failed Suitors

The challenge attracted suitors from across the known world. Princes, heroes, and ambitious young men of various backgrounds came to Arcadia, each convinced that his speed or determination would be enough to win the race and claim Atalanta as his bride.

The races were held on a specially prepared track outside the city, with King Iasus and his court serving as witnesses. Atalanta would give each suitor a head start, then pursue him with her supernatural speed. The courses varied—sometimes straight sprints, sometimes longer races that tested endurance as well as speed—but the outcome was always the same.

“She runs like the wind itself,” observers would whisper as they watched Atalanta overtake suitor after suitor. “Her feet barely seem to touch the ground, and her breathing remains steady even as her opponents collapse from exhaustion.”

One by one, the failed suitors met their fate. Some were young men motivated by love or infatuation with Atalanta’s beauty. Others were ambitious nobles who saw marriage to her as a path to power. A few were simply confident in their own athletic abilities and believed they could succeed where others had failed.

Each failure weighed on Atalanta’s conscience, despite her conviction that she was acting within her rights. She took no pleasure in these deaths, but she was also determined not to sacrifice her independence for the sake of men who sought to claim her like a prize.

Enter Hippomenes

Among those who witnessed one of these fatal races was a young man named Hippomenes, sometimes called Melanion in different versions of the story. Unlike the previous suitors, Hippomenes was not initially interested in competing for Atalanta’s hand. He came as a spectator, curious about the famous huntress but skeptical of the men who risked their lives for the chance to marry her.

“What fools these men are,” Hippomenes thought as he watched another suitor fail and face execution. “To risk death for marriage to a woman who clearly has no interest in any of them? Better to admire her from afar and live to see another day.”

But when he actually saw Atalanta run—her grace, her speed, her fierce beauty as she moved like a goddess across the track—his perspective changed entirely. He found himself enchanted not just by her physical beauty, but by her strength, her independence, and the dignity with which she bore the burden of these unwanted contests.

“Forgive me, all you who have fallen,” he whispered as he watched her. “I understand now why you were willing to risk everything. She is indeed worth any sacrifice.”

Yet Hippomenes was no fool. He could see that Atalanta’s speed was beyond mortal capabilities, and he knew that his own athletic abilities, while respectable, were nowhere near sufficient to defeat her in a fair race. If he was to win her hand, he would need more than speed—he would need cunning and divine assistance.

The Appeal to Aphrodite

Recognizing that he could not succeed through his own abilities alone, Hippomenes turned to the gods for help. He went to a temple of Aphrodite, goddess of love, and offered prayers and sacrifices while explaining his situation.

“Great Aphrodite,” he prayed, “I know that Atalanta has dedicated herself to Artemis and sworn to remain unmarried. But I believe that love is stronger than any vow, and that even the most independent heart can be won by the right approach. Help me devise a way to win her hand without compromising her honor or my own.”

Aphrodite, who had long been annoyed by Atalanta’s devotion to Artemis and her rejection of love and marriage, was intrigued by Hippomenes’ request. Here was an opportunity to prove that love was more powerful than chastity, that even Artemis’s most devoted follower could be brought under Aphrodite’s influence.

“Your prayer pleases me,” the goddess said, appearing to Hippomenes in his dreams. “I will give you the means to win your race, but you must use them wisely. Atalanta’s speed is indeed supernatural, but every runner can be distracted, and every woman—even the most independent—has desires that can be awakened.”

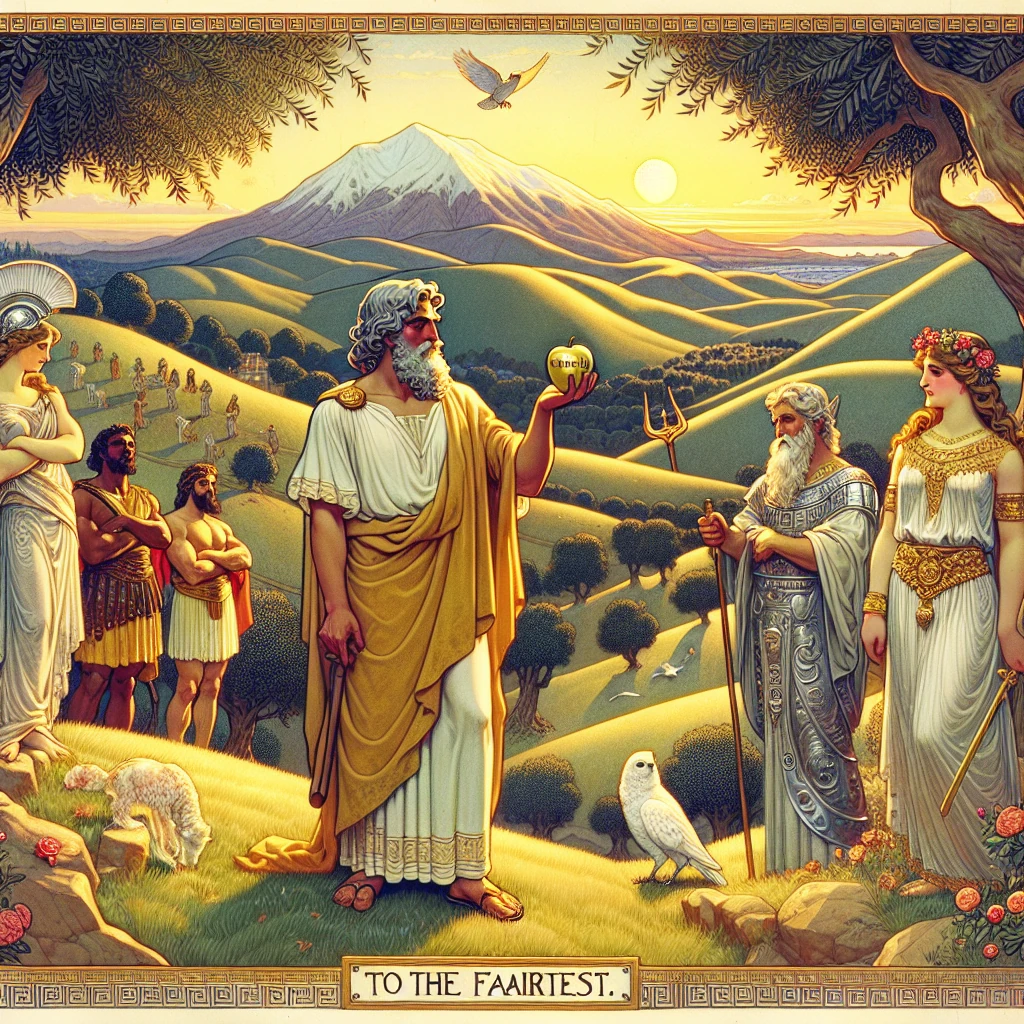

When Hippomenes awoke, he found beside his bed three golden apples, each one perfectly formed and glowing with an inner light that spoke of their divine origin. They were irresistibly beautiful, the kind of treasures that could catch anyone’s attention and awaken covetousness in even the most disciplined heart.

“These are from the garden of the Hesperides,” Aphrodite’s voice whispered in his mind. “Use them wisely during your race, and you will find that even divine speed can be overcome by mortal cleverness and divine assistance.”

The Fateful Race

Armed with Aphrodite’s golden apples, Hippomenes presented himself to King Iasus and formally requested the right to race Atalanta for her hand. The king, who had grown somewhat weary of the repeated failures and executions, nevertheless approved the contest according to the established rules.

Atalanta, for her part, looked upon this new suitor with mixed feelings. She could see that he was handsome and appeared more thoughtful than many of her previous challengers. There was something in his manner that suggested he understood the gravity of what he was attempting, yet he seemed confident rather than desperate.

“Are you certain you wish to do this?” she asked him privately before the race. “I take no pleasure in these deaths, and you seem like a man of intelligence and worth. Surely there are other women who would welcome your suit without requiring you to risk your life.”

Hippomenes looked into her eyes and spoke with complete sincerity. “I have watched you race, Princess Atalanta, and I have seen not just your speed but your grace, your strength, and your nobility. I would rather die trying to win your hand than live knowing I was too cowardly to make the attempt.”

His words stirred something in Atalanta’s heart—the first time she had felt any real attraction to one of her suitors. Yet she was also bound by her vows and her principles. “Then let us race,” she said, “and may the gods decide both our fates.”

The Strategy Unfolds

The race began like all the others, with Atalanta giving Hippomenes a substantial head start before beginning her pursuit. As expected, her supernatural speed quickly began to close the gap between them, and spectators prepared to witness another tragic failure.

But as Atalanta drew near to him, Hippomenes threw the first golden apple off to one side of the track. The apple’s divine beauty caught Atalanta’s eye immediately, and despite her focus on the race, she found herself irresistibly drawn to it. Almost without conscious thought, she veered off course to retrieve the precious object.

The brief delay allowed Hippomenes to regain his lead, but Atalanta quickly resumed her pursuit. Once again, she began to overtake him, her divine speed making up for the lost time. And once again, as she drew close, Hippomenes threw another golden apple, this time to the other side of the track.

Again, Atalanta found herself compelled to retrieve the beautiful object, unable to resist its supernatural allure. This second delay gave Hippomenes an even greater lead, but still, Atalanta’s speed was bringing her closer to victory.

As they approached the finish line and Atalanta began to overtake him for the final time, Hippomenes threw the third and final golden apple. This time, he threw it further off the track than before, forcing Atalanta to run even further to retrieve it.

The delay was just enough. As Atalanta grasped the final apple and turned back toward the track, she saw Hippomenes cross the finish line ahead of her. For the first time in her life, she had been defeated in a race.

Victory and Consequence

The crowd erupted in amazement and celebration. Finally, someone had managed to defeat the unbeatable Atalanta, and by doing so with cleverness rather than just speed, Hippomenes had won not just the race but considerable respect from the spectators.

Atalanta, standing at the finish line with the three golden apples in her hands, felt a complex mixture of emotions. She was surprised by her defeat, certainly, but she also felt a strange sense of relief. The burden of these deadly races had weighed on her conscience, and there was something appealing about finally being defeated by someone who had used wit rather than brute force.

Moreover, she found herself genuinely attracted to Hippomenes. His cleverness in devising a strategy to defeat her, his courage in risking his life, and his respectful treatment of her both before and after the race all impressed her. For the first time, she could imagine herself willingly entering into marriage with someone.

“You have won fairly,” she told him as they stood together before King Iasus and his court. “I will honor my pledge and marry you, and I find that the prospect does not displease me as much as I had expected.”

The wedding of Atalanta and Hippomenes was celebrated throughout Arcadia as a triumph of love over independence, of cleverness over brute force, and of persistence over seemingly impossible odds. The couple seemed genuinely happy together, and for a time, it appeared that all had ended well.

The Forgotten Gratitude

In their happiness and excitement, however, Hippomenes made a crucial error. He forgot to offer proper thanks to Aphrodite for her assistance in winning the race. The three golden apples had been divine gifts, and his victory had been achieved through the goddess’s intervention, yet in his joy at winning Atalanta’s hand, he neglected to acknowledge the debt he owed.

This oversight would prove costly, for Aphrodite was not a goddess who tolerated ingratitude. She had risked her own relationship with Artemis by helping Hippomenes win over one of the virgin goddess’s most devoted followers, and she expected appropriate recognition for her assistance.

“Does he think his victory was due to his own cleverness alone?” Aphrodite mused as she watched the wedding celebrations from Olympus. “Does he believe that mortal wit could have overcome divine speed without divine assistance? This ingratitude requires correction.”

The goddess began to plan her revenge, waiting for the right moment to remind Hippomenes of what he owed her and to demonstrate the consequences of failing to honor the gods who provide aid to mortals.

The Divine Punishment

The opportunity for Aphrodite’s revenge came when Atalanta and Hippomenes were traveling together and decided to rest in a sacred grove. Unbeknownst to them, this grove was particularly sacred to either Zeus or Cybele (depending on the version of the story), and it was forbidden for mortals to engage in lovemaking within its boundaries.

Aphrodite filled both Atalanta and Hippomenes with overwhelming desire for each other, a passion so strong that they could not control themselves despite being in a sacred place. They made love in the grove, unknowingly committing sacrilege that would bring down divine wrath upon them.

The god or goddess whose grove they had defiled was furious at this violation of sacred space. As punishment for their sacrilege, both Atalanta and Hippomenes were transformed into lions and condemned to pull the chariot of Cybele, the Great Mother goddess.

In some versions of the story, this transformation was seen as particularly cruel because the ancient Greeks believed that lions could not mate with each other, only with leopards. Thus, the couple who had found love were condemned to spend eternity together but unable to express their love physically.

The Legacy of the Golden Apples

The story of Atalanta and the golden apples became one of the most enduring tales in Greek mythology, resonating through the ages as a complex exploration of themes that remain relevant today. It raises questions about the nature of independence and love, the role of cleverness versus strength, and the consequences of making bargains with the gods.

Atalanta herself became a symbol of female independence and athletic prowess, inspiring later generations of women who sought to excel in traditionally male domains. Her skill as a huntress and her unwillingness to be forced into unwanted marriage made her a powerful figure for those who valued personal autonomy over social convention.

Yet the story also demonstrates the complexities of trying to maintain complete independence in a world where relationships and community ties are important. Atalanta’s eventual marriage to Hippomenes suggests that even the most independent person may find value in partnership, provided it is entered into freely and with mutual respect.

The golden apples themselves became symbols of irresistible temptation and the power of beauty to distract even the most focused individual. They represented the idea that everyone, no matter how strong or determined, has desires that can be exploited by those clever enough to identify and manipulate them.

Hippomenes’ victory through cunning rather than strength offered a different model of masculine success, one that relied on intelligence and strategy rather than brute force. His use of divine assistance raised questions about the ethics of seeking supernatural aid in mortal competitions, while his subsequent punishment demonstrated the importance of showing proper gratitude to the gods.

The transformation of both lovers into lions served as a reminder that mortals who achieve their desires through divine assistance must be prepared to face divine consequences as well. Their punishment showed that the gods’ gifts always come with a price, and that forgetting to acknowledge divine favor is a form of hubris that the gods will not tolerate.

Modern Interpretations

In contemporary readings, the story of Atalanta and the golden apples has been interpreted in various ways. Some see it as a tale about the conflict between personal autonomy and social expectations, with Atalanta representing those who struggle to maintain their independence in societies that pressure them to conform to traditional roles.

Others view it as a story about the nature of love and partnership, suggesting that true love involves mutual respect and that even the most independent person can benefit from finding the right partner. Hippomenes’ approach—winning through cleverness and showing respect for Atalanta’s autonomy—is seen as a model for how courtship should proceed.

Feminist interpretations often focus on Atalanta as a powerful female figure who carved out her own path in a male-dominated world, while also examining how even strong women can be undermined by societal pressures and divine machinations beyond their control.

The golden apples have been interpreted as symbols of material temptation, sexual desire, or the power of beauty to corrupt judgment. In some readings, they represent the way that external forces can manipulate our desires and lead us away from our intended paths.

The story continues to resonate because it addresses fundamental questions about human nature and relationships that remain relevant across cultures and centuries. It reminds us that independence and love are not necessarily incompatible, that cleverness can sometimes triumph over strength, and that achieving our desires often requires us to navigate complex moral and practical considerations.

Most importantly, it serves as a reminder that all victories come with consequences, all gifts require gratitude, and that the choices we make in pursuit of our goals can have effects that extend far beyond what we initially imagine. The tale of Atalanta and the golden apples remains one of mythology’s most nuanced explorations of desire, independence, and the complex relationships between mortals and the divine forces that shape their destinies.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus