Achilles and the Trojan War

Story by: Homer and Various Greek Poets

Source: Greek Mythology

Among all the heroes who sailed to Troy, none was more celebrated, more feared, or more tragic than Achilles, son of Peleus and the sea-goddess Thetis. His story is one of divine prophecy and mortal choice, of friendship and rage, of the price of glory and the inevitability of fate. The tale of Achilles and his role in the Trojan War became the foundation of Homer’s Iliad, one of the greatest epic poems ever composed, and continues to resonate as a powerful exploration of what it means to be human in the face of destiny.

The Prophecy of Two Fates

Achilles was born into a destiny that was both magnificent and terrible, shaped by a prophecy that would haunt him throughout his short life. Before his birth, the Fates had revealed to his mother Thetis that her son would face a choice between two destinies: he could live a long, peaceful life in obscurity, forgotten by history, or he could achieve immortal glory through great deeds but die young in battle.

“My son,” Thetis would tell the young Achilles as he grew to manhood, “the threads of your fate are woven in patterns that cannot be changed. You must choose whether to value length of days or eternal fame, whether to live as an ordinary mortal or die as a legendary hero.”

This prophecy weighed heavily on both mother and son. Thetis, desperate to protect her child, had attempted to make him invulnerable by dipping him as an infant in the waters of the River Styx. The divine waters rendered his entire body immune to harm—except for his heel, where she had held him during the immersion. This one vulnerable spot would prove to be his undoing, giving rise to the phrase “Achilles’ heel” to describe a fatal weakness.

As Achilles reached manhood, he was trained by Chiron, the wisest of the centaurs, who taught him not only the arts of war but also music, medicine, and philosophy. Under Chiron’s guidance, Achilles became the perfect warrior—swift as the wind, strong as a lion, and skilled with every weapon. Yet he also developed a complex character, capable of great tenderness and friendship as well as terrible rage when his honor was threatened.

The Call to War

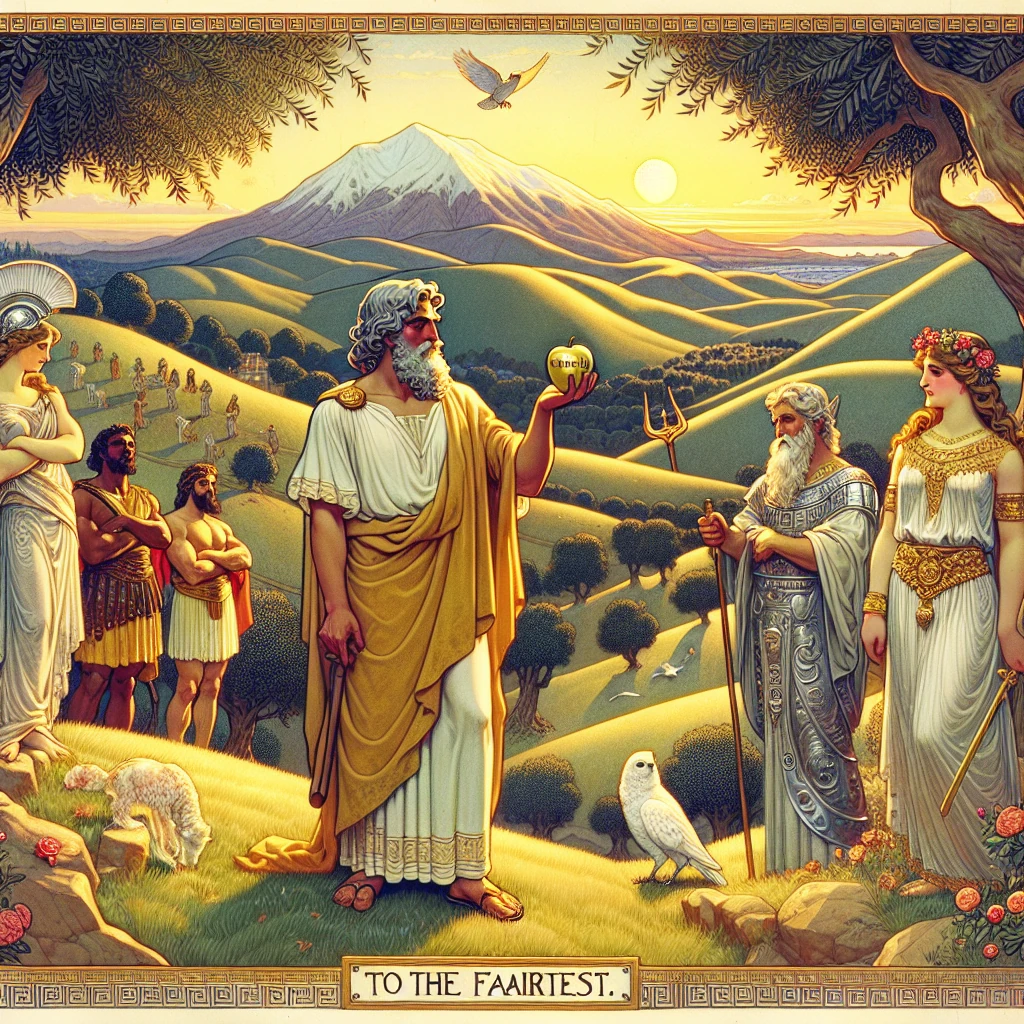

When Paris of Troy abducted Helen from Sparta, her husband Menelaus called upon all the Greek kings who had once courted her to honor their oath to defend her marriage. This oath, sworn years before, bound the greatest warriors of Greece to come to Menelaus’s aid if Helen were ever threatened.

Among those summoned was Achilles, though he had been too young to be one of Helen’s original suitors. His presence was requested because the Greeks had received a prophecy that Troy could not be taken without his participation. When the Greek leaders came to recruit him, they found both opportunity and resistance.

Thetis, knowing that participation in the Trojan War would lead to her son’s early death, had disguised Achilles as a girl and hidden him among the daughters of King Lycomedes on the island of Scyros. There, ironically, Achilles had fathered a son, Neoptolemus, with one of the king’s daughters, Deidamia.

But Odysseus, renowned for his cleverness, devised a plan to identify Achilles among the disguised women. He arrived at Lycomedes’ court as a merchant, offering gifts of jewelry and fine clothing to the king’s daughters. Hidden among these feminine gifts, however, were weapons and armor.

When a trumpet sounded what appeared to be an alarm for attack, all the real women fled in terror. But Achilles instinctively reached for the weapons, revealing his identity. Faced with exposure and recognizing that fate could not be avoided forever, Achilles agreed to join the expedition to Troy.

The Wrath of Achilles

The early years of the Trojan War established Achilles as the Greeks’ greatest champion. His prowess in battle was legendary—he led successful raids on Trojan allies, captured numerous cities, and struck fear into the hearts of all who faced him. His very presence on the battlefield could turn the tide of combat, and the Trojans learned to retreat when they saw his distinctive armor and blazing eyes.

But Achilles’ greatest weakness was his pride and his sensitivity to any perceived slight to his honor. This flaw would lead to the central crisis of the war and provide the opening theme of Homer’s Iliad: “Sing, goddess, of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus, that rage which brought countless sufferings to the Greeks.”

The crisis began in the war’s tenth year with a seemingly minor incident. Agamemnon, the Greek commander-in-chief, had taken as his war prize a Trojan priest’s daughter named Chryseis. When her father, Chryses, attempted to ransom her back, Agamemnon rudely refused and threatened the old priest.

Chryses, who served Apollo, prayed to his god for vengeance. Apollo responded by sending a plague upon the Greek camp, and arrows from his silver bow brought disease and death to men and animals alike. The army began to weaken and demoralize as the plague raged for nine days.

On the tenth day, Achilles called for an assembly to address the crisis. Calchas, the army’s prophet, revealed that the plague would only end when Chryseis was returned to her father without ransom. Faced with this divine mandate, Agamemnon was forced to give up his prize.

But Agamemnon, furious at this public humiliation, decided to compensate for his loss by taking someone else’s war prize. His eyes fell upon Briseis, a beautiful Trojan woman who had been awarded to Achilles. “If I must give up my prize,” Agamemnon declared, “then I will take yours, Achilles. This will remind everyone who commands this army.”

The Withdrawal from Battle

Achilles was outraged by what he saw as a massive violation of his honor and the army’s established customs. Briseis was not just a war prize to him—she had become dear to him, and more importantly, she represented recognition of his achievements and status among the Greeks.

“You have the face of a dog and the heart of a deer!” Achilles shouted at Agamemnon before the assembled army. “You who never dare to face the enemy in battle, you who take the prizes that others have won with their blood and courage! Take the woman, but know this—I will not fight for you anymore. You and your army can face Hector and the Trojans without me.”

Achilles withdrew to his ships with his followers, the Myrmidons, and refused to participate in any further fighting. He spent his days playing his lyre, singing songs of heroic deeds, and nursing his wounded pride while his closest companion, Patroclus, tried to comfort him.

The absence of Achilles from the battlefield immediately transformed the war. Without their greatest champion, the Greeks began to suffer defeat after defeat. Hector, Troy’s greatest warrior and prince, led increasingly bold attacks, pushing the Greeks back toward their ships and threatening to burn their entire fleet.

Desperate Greek leaders, including Odysseus, Ajax, and Phoenix (Achilles’ old tutor), came to plead with Achilles to return to battle. They offered him magnificent gifts—gold, bronze tripods, horses, and even the return of Briseis along with additional women. Agamemnon even offered one of his own daughters in marriage along with several cities as a dowry.

But Achilles remained unmoved. “Agamemnon has dishonored me before the entire army,” he declared. “No amount of treasure can restore honor once it has been taken away. Let him learn the value of what he has rejected. As for me, I am considering sailing home to live the long, peaceful life that fate has offered me as an alternative to glory.”

The Death of Patroclus

As the military situation grew increasingly desperate for the Greeks, Patroclus could no longer bear to watch his countrymen suffer while he and Achilles remained inactive. Patroclus was more than just Achilles’ closest friend—they had been raised together since childhood, and many believed they were lovers as well as companions in arms.

“My friend,” Patroclus pleaded with Achilles as they watched smoke rise from the Greek ships under Trojan attack, “if you will not fight yourself, at least let me lead the Myrmidons into battle. Lend me your armor so that the Trojans will think you have returned to the fight. The very sight of your equipment might be enough to turn the tide.”

Achilles, moved by his friend’s distress and the desperate situation of their countrymen, agreed to this compromise. “Take my armor and my men,” he said, “but promise me this—once you have driven the Trojans away from our ships, return immediately. Do not pursue them toward the city, for I fear what might happen if you go too far without me.”

Patroclus donned Achilles’ distinctive armor, took up his spear (though not the great ash spear that only Achilles could wield), and led the Myrmidons into battle. The psychological effect was immediate—the Trojans, seeing what they believed was Achilles returning to the fight, began to fall back in terror.

Patroclus fought magnificently, driving the Trojans away from the ships and pursuing them across the plain toward Troy. In his excitement and battle-fury, however, he forgot Achilles’ warning about not going too far. He pressed his attack all the way to the walls of Troy itself, where he was finally confronted by Hector.

The battle between Patroclus and Hector was fierce but unequal. Though Patroclus was a skilled warrior, he was no match for Troy’s greatest defender. After a long fight, Hector’s spear found its mark, and Patroclus fell dying beneath the walls of Troy, Achilles’ armor scattered around his body.

The Return of Achilles

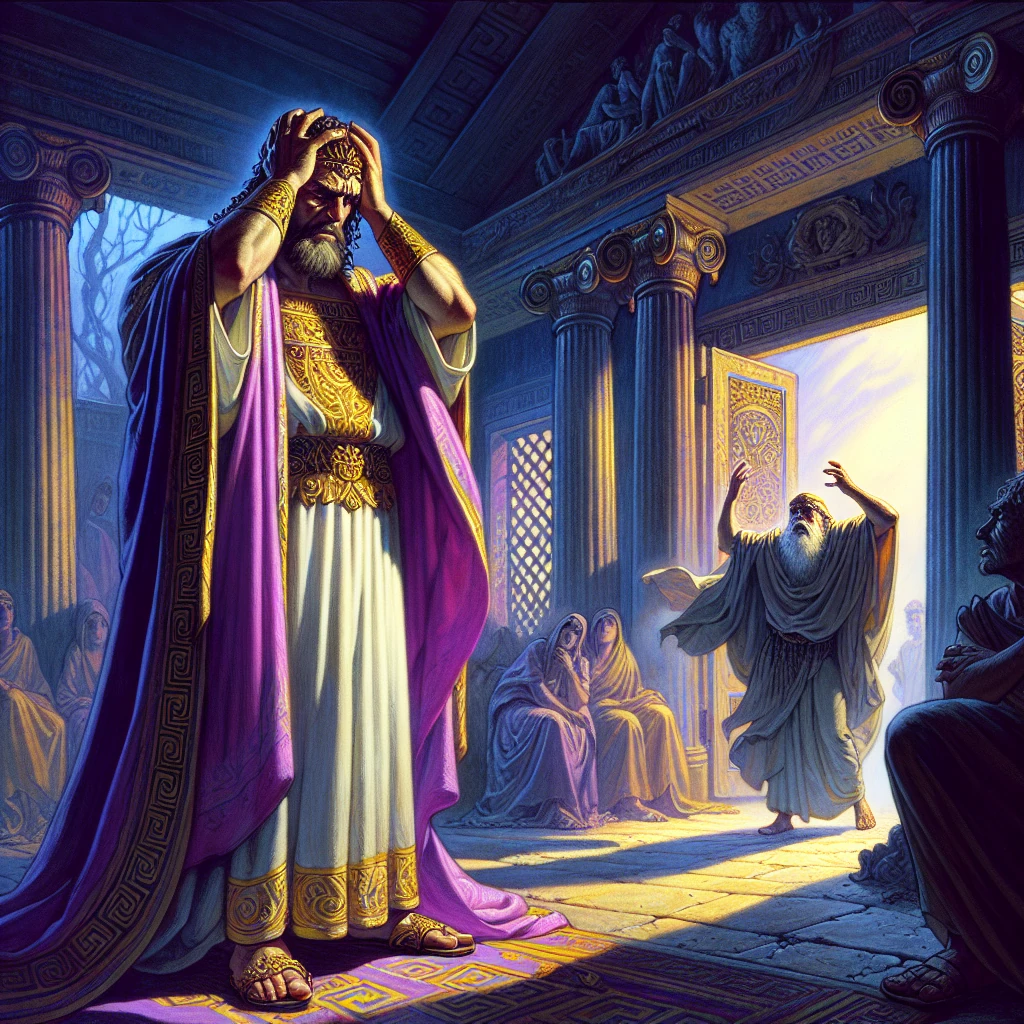

When word reached Achilles that Patroclus had been killed and his armor taken by Hector, the hero’s reaction was immediate and terrible. His rage at Agamemnon was nothing compared to the fury that now consumed him. He rolled in the dirt, tore his hair, and cried out in anguish that could be heard across the entire Greek camp.

Thetis, his mother, rose from the sea depths when she heard her son’s cries of grief. She found him inconsolable, consumed by a desire for revenge that overshadowed all other considerations.

“My son,” she said sadly, “if you pursue this vengeance against Hector, your own death will follow soon after. The Fates have decreed that your end comes quickly after his.”

“Then let me die quickly,” Achilles replied, his eyes blazing with grief and rage. “What good is life to me now that Patroclus is dead? I failed to protect him, and now I must avenge him or live forever in shame. I no longer care about the choice between long life and glory—I choose revenge, whatever the cost.”

Knowing she could not change her son’s mind, Thetis asked Hephaestus, god of the forge, to create new armor for Achilles. The divine smith crafted a magnificent set of armor, including a shield decorated with scenes of the entire world—cities at peace and war, farmers and warriors, the ocean and the stars.

When Achilles appeared on the battlefield in his new divine armor, the very sight struck terror into Trojan hearts. He moved like a force of nature, cutting down enemies with superhuman fury. Warriors fled before him, and even the River Scamander tried to stop his advance when its waters became choked with Trojan bodies.

The Duel with Hector

The climax of Achilles’ revenge came when he finally confronted Hector beneath the walls of Troy. The Trojan prince knew that facing Achilles in single combat meant almost certain death, but he also knew that he could not continue to avoid the confrontation without dishonoring himself and failing in his duty to defend his city.

Before the duel, Hector made one final attempt at diplomacy. “Achilles,” he called out, “let us make a pact. If I kill you, I will return your body to the Greeks for proper burial. If you kill me, promise to do the same for my body.”

But Achilles was beyond such civilized agreements. “There are no pacts between lions and lambs,” he replied. “You killed Patroclus, and for that, you must die. There will be no mercy, no honor, only vengeance.”

The duel that followed was epic in its scope and tragic in its outcome. Hector fought bravely, but Achilles was driven by superhuman rage and protected by divine armor. When Achilles’ spear finally found the one gap in Hector’s armor—at the throat, where the collarbone meets the neck—the Trojan prince fell dying in the dust.

Even in death, Achilles’ rage was not satisfied. He tied Hector’s body to his chariot and dragged it around the walls of Troy while Hector’s parents, wife, and son watched in horror from the battlements. For twelve days, he continued this desecration, driving around Patroclus’s tomb with Hector’s body trailing behind his horses.

The Ransom of Hector

The gods, appalled by Achilles’ treatment of Hector’s corpse, finally intervened. Zeus sent Iris to summon Thetis and commanded her to tell her son that he must accept ransom for Hector’s body. At the same time, Hermes guided Priam, king of Troy and Hector’s father, safely through the Greek camp to Achilles’ tent.

The meeting between Achilles and Priam became one of the most powerful scenes in all of literature. The old king, having lost his greatest son, knelt before the man who had killed him and appealed not to Achilles’ anger but to his humanity.

“Achilles,” Priam said, “remember your own father, Peleus, who is of the same age as I. Think of how he would grieve if you were killed and your body was dishonored. I have done what no man should have to do—I have kissed the hands of the man who killed my son. Have pity on an old man’s grief.”

These words broke through Achilles’ rage and reminded him of his own mortality and the grief his death would bring to his father. He wept—for Patroclus, for Hector, for Priam, and for himself. In that moment of shared grief, enemy recognized enemy as fellow sufferer in the tragedy of war.

Achilles accepted Priam’s ransom and returned Hector’s body, even granting a twelve-day truce so that Troy could properly mourn and bury its greatest hero. It was a moment of grace in the midst of brutal war, a reminder that even in conflict, humanity and compassion could still surface.

The Death of Achilles

Though Homer’s Iliad ends with Hector’s funeral, the story of Achilles continued. As his mother had prophesied, his death came soon after his revenge was complete. The specific details of his death vary in different accounts, but all agree that it came through divine intervention and involved his one vulnerable spot.

In the most famous version, Achilles was killed by an arrow shot by Paris and guided by Apollo. The arrow struck his heel—the one spot where the waters of the Styx had not touched him—and proved fatal despite his near-invulnerability elsewhere. Some accounts suggest that Paris shot the arrow from ambush; others describe it happening during open battle.

Achilles’ death sent shockwaves through both armies. The Greeks mourned the loss of their greatest champion, while the Trojans celebrated but also recognized that his death had come at a tremendous cost—they had lost Hector and many other heroes to Achilles’ rage.

The hero’s funeral was magnificent, befitting his status and achievements. His body was burned on a great pyre along with the bodies of animals and, according to some accounts, Trojan prisoners. His ashes were mixed with those of Patroclus, and both were placed in a golden urn made by Hephaestus.

Thetis organized funeral games in her son’s honor, with competitions in chariot racing, boxing, wrestling, and other martial arts. Heroes from across the Greek army participated, and the prizes were magnificent—armor, weapons, and precious metals that reflected Achilles’ importance to the war effort.

The Legacy of Achilles

The death of Achilles marked a turning point in the Trojan War, but his influence continued to shape events even after his passing. His divine armor became the subject of a fierce competition between Ajax and Odysseus, ultimately contributing to Ajax’s suicide when the armor was awarded to Odysseus.

His son Neoptolemus, brought from Scyros to complete the war, proved to be as fierce and effective a warrior as his father, though perhaps lacking some of Achilles’ more noble qualities. Neoptolemus played a crucial role in the final stages of the war, including the sack of Troy itself.

The example of Achilles’ choice between long life and eternal glory influenced countless heroes throughout antiquity. His decision to pursue honor and vengeance despite knowing it would lead to his death became a model for heroic behavior, even as it also served as a warning about the costs of such choices.

The Character of Achilles

What makes Achilles such a compelling figure in mythology is not just his prowess in battle, but the complexity of his character. He was capable of great tenderness—his relationship with Patroclus demonstrated deep loyalty and love, and his final scene with Priam showed his capacity for compassion and wisdom.

Yet he was also prone to devastating rage and prideful behavior that could hurt both enemies and allies. His withdrawal from battle due to wounded pride led to countless Greek deaths, including that of his beloved Patroclus. His treatment of Hector’s body violated every standard of honor and decency recognized by both sides in the war.

This combination of nobility and flaw, of superhuman ability and very human weakness, made Achilles a perfect vehicle for exploring themes that resonated with Greek audiences and continue to speak to modern readers. He embodied the tragic hero—someone whose great strengths are inseparable from equally great weaknesses.

Themes and Significance

The story of Achilles explores several enduring themes that have made it relevant across cultures and centuries. The tension between individual honor and collective responsibility runs throughout his tale—his personal grievances with Agamemnon led him to abandon his duty to his fellow Greeks, with devastating consequences.

The relationship between mortality and glory forms another central theme. Achilles’ choice between long life and eternal fame reflects fundamental questions about what makes life meaningful and what price we should be willing to pay for lasting recognition.

The nature of friendship and love is examined through Achilles’ relationship with Patroclus. Their bond was so strong that Patroclus’s death could drive Achilles to abandon his withdrawal from battle and embrace his own doom. This suggests that love and loyalty to others can be more powerful motivators than even self-preservation.

The cycle of violence and revenge is illustrated through Achilles’ pursuit of Hector. His desire for vengeance was understandable given his grief over Patroclus, but his excessive treatment of Hector’s body showed how revenge can corrupt even noble impulses and perpetuate cycles of suffering.

Historical and Cultural Impact

The figure of Achilles had enormous influence on ancient Greek culture and continues to resonate in modern literature and popular culture. For the Greeks, he represented the ideal of the heroic warrior—someone willing to sacrifice everything for honor and glory.

Alexander the Great consciously modeled himself on Achilles, carrying a copy of the Iliad with him on his campaigns and claiming descent from the hero. Many other military leaders throughout history have invoked Achilles as an example of warrior excellence and heroic determination.

In literature, Achilles became the archetypal tragic hero whose greatest strengths lead inevitably to his downfall. Writers from Virgil to Shakespeare to modern novelists have drawn inspiration from his story, using it to explore questions about honor, duty, friendship, and the human condition.

The phrase “Achilles’ heel” has entered common usage to describe any fatal weakness, even in someone who appears otherwise invulnerable. This linguistic legacy demonstrates how powerfully the story has embedded itself in human consciousness.

Modern Interpretations

Contemporary readers often focus on different aspects of Achilles’ story than ancient audiences did. While the Greeks might have emphasized his martial prowess and pursuit of glory, modern interpretations often examine the psychological cost of war, the nature of male friendship, and the critique of military culture implicit in his story.

Some scholars see in Achilles’ rage a reflection of post-traumatic stress disorder, interpreting his excessive reactions and difficulty controlling his emotions as symptoms of psychological trauma caused by prolonged warfare. This reading emphasizes the human cost of conflict and the way violence can damage even those who excel at it.

Others focus on the homoerotic elements of his relationship with Patroclus, seeing their bond as an example of romantic love that transcends gender categories. This interpretation emphasizes themes of love, loss, and the lengths to which people will go to avenge those they care about most deeply.

Feminist readings often examine how Achilles’ story reflects and reinforces certain concepts of masculinity, particularly the association of honor with violence and the expectation that men should be willing to die rather than accept perceived humiliation.

Conclusion

The story of Achilles and the Trojan War remains one of the most powerful and enduring narratives in world literature because it addresses fundamental questions about human nature and the human condition. Through the figure of this complex hero, we explore what it means to choose between competing values—safety and glory, individual honor and collective responsibility, love and duty.

Achilles’ tale reminds us that our greatest strengths often contain the seeds of our greatest weaknesses, that the pursuit of honor and recognition can lead to both magnificent achievements and terrible consequences. His choice to embrace a short, glorious life over a long, obscure one continues to resonate because it reflects choices we all face about how to live and what to value.

The enduring appeal of his story lies not just in its dramatic action and heroic feats, but in its honest examination of the costs and contradictions inherent in human existence. Achilles achieved the immortal glory he sought—his name and deeds are indeed remembered thousands of years after the Trojan War supposedly took place. Yet the price he paid—his life, his friend’s life, and the suffering of countless others—forces us to question whether such glory is worth its cost.

In the end, Achilles embodies both the highest potential and the most dangerous impulses of human nature. His story serves as both inspiration and warning, celebrating the capacity for heroic achievement while acknowledging the tragic consequences that can flow from our noblest and most destructive impulses. It is this complexity and moral ambiguity that has made the tale of Achilles one of the most compelling and influential stories ever told.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus