The Madness of Sweeney

legend by: Traditional Irish

Source: Irish Medieval Literature

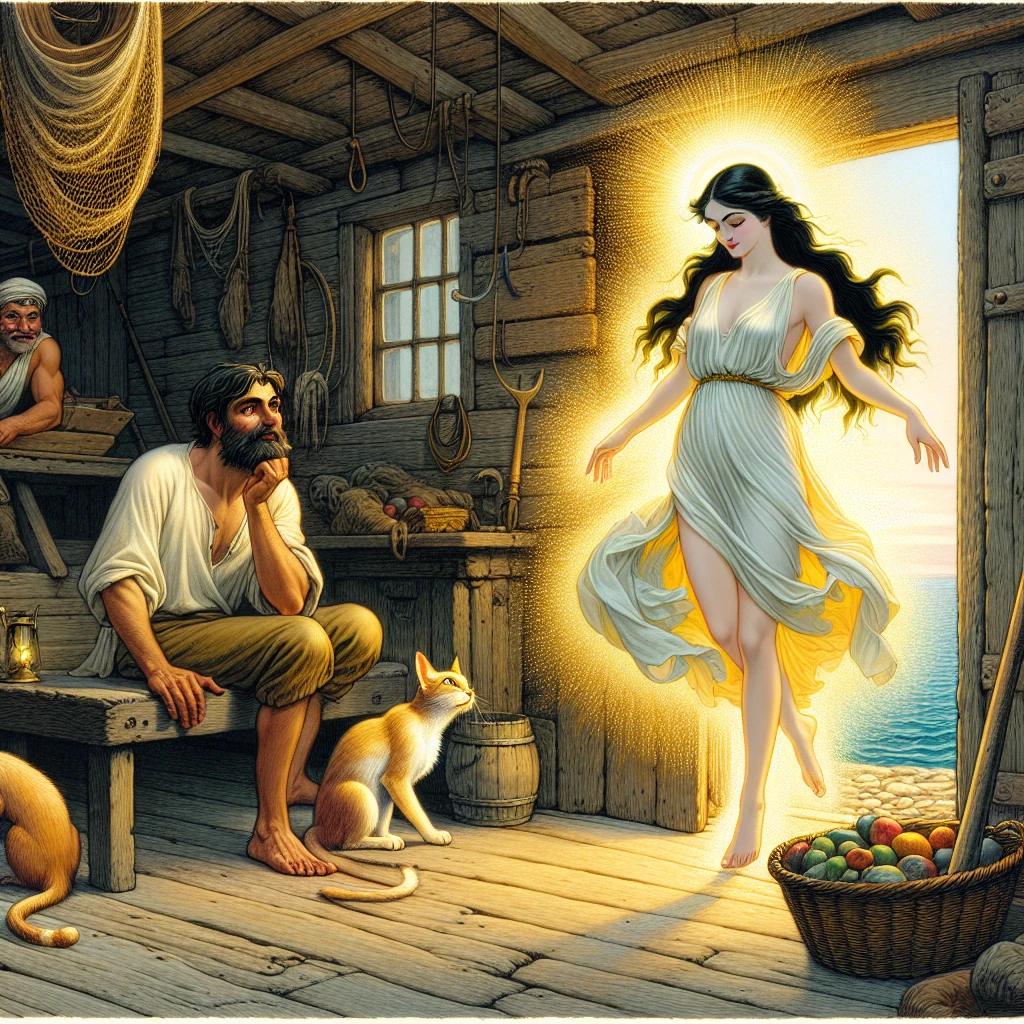

In the chronicles of Ireland, few tales are as strange and beautiful as that of Suibhne Geilt—Sweeney the Mad—who was once a proud king but became a wild man of the woods, living among the birds and beasts while composing poetry of heartbreaking beauty. His story is one of pride, curse, madness, and ultimately, a kind of redemption that comes through suffering and the deep wisdom of the natural world.

The King of Dal Araide

Suibhne mac Colmáin was king of Dal Araide in the north of Ireland, a man of noble bearing and fierce pride. His kingdom was prosperous, his warriors loyal, and his reputation for both courage and cunning was known throughout the land. He was tall and handsome, with golden hair and eyes like blue flame, and when he spoke, his voice carried the authority of one born to command.

But Suibhne’s greatest strength was also his greatest weakness: his pride was as boundless as his courage. He brooked no interference in his affairs, acknowledged no authority higher than his own, and held himself above both the laws of men and the customs of the church that was spreading throughout Ireland.

This pride would be his undoing, for it brought him into conflict with Saint Ronan Finn, a holy man who had come to establish a church within Suibhne’s territory. The king viewed this as an intrusion upon his sovereignty and was determined to drive the saint away.

“I am king here,” Suibhne declared when his advisors suggested he show respect for the holy man. “No foreign god and no wandering priest will dictate terms to me in my own land.”

The Saint’s Mission

Saint Ronan was a man of great learning and deep faith, who had traveled from monastery to monastery spreading the Christian message throughout Ireland. He was gentle by nature but firm in his convictions, and he had received what he believed to be a divine command to establish a church in Dal Araide.

When Ronan began to clear ground for his church on a hill overlooking Suibhne’s royal fortress, the king’s anger blazed like fire. To Suibhne, this was not merely religious presumption but a direct challenge to his royal authority.

“Remove yourself from my lands,” Suibhne commanded when he confronted the saint. “I want no part of your foreign god or your foreign ways.”

But Ronan continued his work with serene determination. “I serve a higher king than any earthly ruler,” he replied calmly. “This church will stand as God wills it, whether mortal kings approve or not.”

Such defiance of his authority was intolerable to Suibhne. In his rage, he seized the saint’s psalter—the book of psalms from which Ronan read his daily prayers—and hurled it into a nearby lake.

“Let your god fish that out of the water if he’s so powerful,” the king sneered, turning to leave.

The Curse Pronounced

Saint Ronan watched sadly as his precious book disappeared beneath the dark waters of the lake. But as he stood there, a miracle occurred—an otter emerged from the lake carrying the psalter in its mouth, the book completely dry and undamaged.

Ronan took this as a sign that God would not allow his work to be frustrated by human pride. He faced the departing king and spoke words that would echo through the ages:

“Suibhne mac Colmáin, your pride has blinded you to all goodness and wisdom. Since you have chosen to act like a wild beast rather than a rational man, like a wild beast you shall live. I curse you to wander the wilderness, naked and mad, finding no peace among men but only among the birds of the air and the beasts of the field.”

Suibhne laughed mockingly at what he saw as empty threats. “Curse away, old man. Your words have no power over a king.”

But even as he spoke, he felt a strange chill in the air, as if the very atmosphere around him had changed. The curse had been spoken, and now it waited only for the moment to fulfill itself.

The Battle of Moira

The opportunity came sooner than anyone expected. War broke out between the Irish kingdoms and the warriors of Dal Riata, led by King Domnall mac Aedo. The conflict, known as the Battle of Moira, would be one of the bloodiest in Irish history.

Suibhne led his warriors into battle with his usual confidence, his golden hair streaming like a banner in the wind and his sword singing its deadly song. For a time, it seemed as if his forces would carry the day, as they had in so many previous conflicts.

But in the midst of the fighting, when the clash of weapons was loudest and the cries of warriors filled the air, something terrible happened to the proud king. The sounds of battle suddenly became unbearable to his ears, like the screaming of demons from the depths of hell.

Terror unlike anything he had ever known seized Suibhne’s heart. The faces of his enemies seemed to transform into monsters, and even his own warriors appeared as creatures from nightmare. The curse of Saint Ronan had found its moment to strike.

With a cry of anguish that rose above the noise of battle, Suibhne cast away his weapons and armor and fled from the field. But this was no ordinary retreat—as he ran, his mind shattered like glass, and madness took hold of his soul.

The Flight to the Wilderness

From that day forward, Suibhne lived as a wild man, naked and alone in the forests and mountains of Ireland. His kingdom passed to another, his family grieved him as dead, and he became a creature of the wilderness, sleeping in trees and eating only nuts, berries, and the occasional fish he could catch with his bare hands.

But though his body had become wild, his mind—fragmented though it was—retained its gifts for poetry and song. In his madness, Suibhne composed verses of startling beauty about his condition, his suffering, and the natural world that had become his home.

He sang of the coldness of winter nights spent in the tops of oak trees, of the loneliness of a man cut off from human fellowship, of the beauty of birds in flight and the changing of the seasons. His poetry captured both the agony of his exile and the strange peace he sometimes found in communion with nature.

“A year since last night I have been among the birds,” he would cry out to the wind. “My body is cold, my heart is heavy, but my spirit soars with the ravens and the eagles.”

The Kindness of Strangers

Though most people feared the mad king and drove him away with stones and curses, some took pity on his condition. A few holy hermits living in the wilderness would sometimes leave food where he could find it, and occasionally a kind soul would offer him shelter for a night.

Most compassionate of all was a woman named Lynseach, the wife of a herdsman, who lived near the forest where Suibhne often wandered. She alone seemed to recognize the nobility that still lived within the madman, and she would secretly leave milk and bread for him near her dwelling.

“He was a king once,” she would tell her husband when he complained about feeding the wild man. “And even mad, he does no harm to anyone but himself. Surely we can spare a little food for one so afflicted.”

Suibhne, in his lucid moments, was deeply grateful for such kindness. He composed some of his most beautiful verses in praise of Lynseach’s generosity, calling her “the bright star in my darkness” and “the proof that human goodness still exists in this harsh world.”

The Wild Companions

As the years passed, Suibhne became so attuned to the natural world that he could communicate with its creatures as if they were old friends. Birds would perch on his shoulders and sing to him, deer would graze peacefully in his presence, and even the wildest animals showed no fear of the mad king.

He learned to read the signs of weather in the flight of birds, to find shelter in the densest forests, and to survive through the harshest winters by following the wisdom of the beasts. In some ways, he became more creature than man, his senses sharpened beyond normal human capacity and his understanding of the natural world deeper than any scholar’s.

Yet he never lost his human heart entirely. In quiet moments, he would remember his former life—his throne, his warriors, his royal halls—and weep for all that he had lost. But increasingly, he also came to see that his madness had brought him a different kind of knowledge, a understanding of truth that was hidden from those who lived conventional lives.

“I have lost a kingdom,” he sang to the wind, “but gained the whole world. I am poorer than the poorest beggar, yet richer than any king.”

The Encounter with Other Madmen

Suibhne was not the only person in Ireland afflicted with supernatural madness. He encountered others who had been driven from human society by various curses and enchantments, and these meetings were among the most poignant in his wandering life.

The most notable was his meeting with Eolann, another warrior-king who had been cursed for his violence and cruelty. Unlike Suibhne, whose madness had gentled his heart, Eolann remained fierce and angry, raging against his fate rather than accepting it.

The two madmen held a strange dialogue in the depths of a dark forest, comparing their sufferings and the different paths their madness had taken them. Through this encounter, Suibhne came to understand that his own suffering had taught him compassion—something he had lacked in his days of pride and power.

“Your madness has made you wise,” Eolann observed with wonder. “Mine has only made me more foolish than before.”

“Perhaps,” Suibhne replied, “wisdom comes not from the madness itself, but from how we choose to bear it.”

The Partial Redemption

After seven years of wandering, Saint Ronan encountered Suibhne in the wilderness. The holy man was older now, his beard white with age, but his eyes still held the same gentle strength that had characterized him when he first pronounced his curse.

Seeing the broken king before him—naked, wild-haired, thin as a scarecrow but somehow possessed of a dignity that suffering had refined rather than destroyed—Ronan felt his heart moved with pity.

“Suibhne,” he said gently, “your pride has been thoroughly humbled. Your suffering has taught you truths that your throne never could. Are you ready now to acknowledge the power of God and seek forgiveness for your past wrongs?”

The mad king looked at the saint with eyes that held both wildness and wisdom. “I acknowledge powers greater than myself,” he said carefully. “I have learned that humanity is but a small part of a vast creation, and that kings are no more important than sparrows in the great scheme of things.”

Moved by this humility, Saint Ronan partially lifted his curse. “You may return to human society if you choose,” he said. “Your mind will be mostly healed, though you may always be somewhat strange to ordinary men. But know this—if you ever again allow pride to rule your heart, the madness will return threefold.”

The Choice of the Wild

Offered the chance to return to civilization, Suibhne faced the hardest decision of his life. He could reclaim some measure of his former existence, perhaps even rule again, but he would have to give up the profound communion with nature that had become his deepest source of meaning.

For days he agonized over this choice, torn between his human longing for companionship and his hard-won understanding of the natural world’s deeper truths. Finally, he made his decision.

“I thank you for your mercy, holy father,” he told Saint Ronan. “But I find that I am no longer entirely human, nor do I wish to be. The wilderness has become my kingdom, the birds my subjects, and the seasons my calendar. This is the life God has given me, and I choose to embrace it fully.”

The saint blessed him and departed, and Suibhne returned to his life among the trees and streams. But now his madness was transformed into a kind of holy wildness, a deliberate choice to live apart from human society in order to serve as a bridge between the human and natural worlds.

The Final Years

Suibhne lived for many more years in the wilderness, and his poetry from this period shows a man who had found peace in his strange exile. He no longer raged against his fate but celebrated the beauty he found in his daily life among the creatures of forest and field.

Pilgrims and holy men would sometimes seek him out, drawn by reports of the mad king who had become a sage of the wilderness. They would find him living in perfect harmony with his environment, his words full of wisdom about the interconnectedness of all living things.

His death, when it finally came, was as strange and beautiful as his life had been. According to legend, he was found one morning sitting peacefully beneath an ancient oak tree, his face turned toward the rising sun, surrounded by birds that sang in mourning for their departed friend.

The Legacy of Madness

The story of Suibhne’s madness became one of the most beloved tales in Irish literature, inspiring countless retellings and adaptations. But more than its literary value, the tale offered profound insights into the nature of wisdom, suffering, and the relationship between humanity and the natural world.

It suggested that sometimes what the world calls madness might actually be a different kind of sanity—a way of seeing that transcends the limited perspectives of conventional society. Suibhne’s curse became a blessing, his exile a homecoming, and his madness a doorway to wisdom.

The tale reminds us that pride and the lust for power can indeed lead to destruction, but that even the worst suffering can be transformed into something meaningful if we have the courage to embrace it fully. Sometimes the greatest kings are not those who rule over men, but those who have learned to live in harmony with all of creation.

In Ireland today, when people speak of unconventional wisdom or the beauty that can be found in simplicity, they often remember Suibhne—the mad king who lost everything but found in that loss a treasure greater than any crown.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus