The King with the Horse’s Ears

Folktale by: Irish Folklore

Source: Traditional Irish Tale

There was once a king whose ears were the ears of a horse. They were not ugly as such things go, but they were unmistakable, and the king—being vain as a magpie—hid them beneath a velvet cap and commanded that none should speak of them on pain of silence forever.

Each spring, the hair beneath the cap grew hot and restive, and the king needed a barber with careful hands. That year they chose young Donnchadh, a barber whose razors were kind and whose eyes knew how to look away.

The guards led him to a room of polished wood where sunlight fell in squares. Donnchadh bowed. The king removed his cap. The ears sprang free like sails in a wind.

“Do your work,” the king said, not unkindly. “And remember what you are not to remember.”

Donnchadh trimmed and combed and said nothing. But silence is a heavy cloak for a slight man. When he left the castle, the secret sat on his chest like a sleeping cat.

For days he could not eat; for nights he could not sleep. He put his head under a pillow, but the secret crawled under with him. He sang to drown it, but the secret learned the tune. At last, at the edge of a bog where reeds grew thick as hair, he fell to his knees.

“If I don’t tell someone,” he whispered, “I will pop like a seed on the griddle.”

The bog did not object. The wind shushed him kindly. Donnchadh bent to the reeds and whispered into their hollow throats: “The king has horse’s ears.” He said it three times, softly, as if telling a child that thunder is only sky furniture being moved.

At once he felt lighter, and the reeds trembled as if pleased to be included.

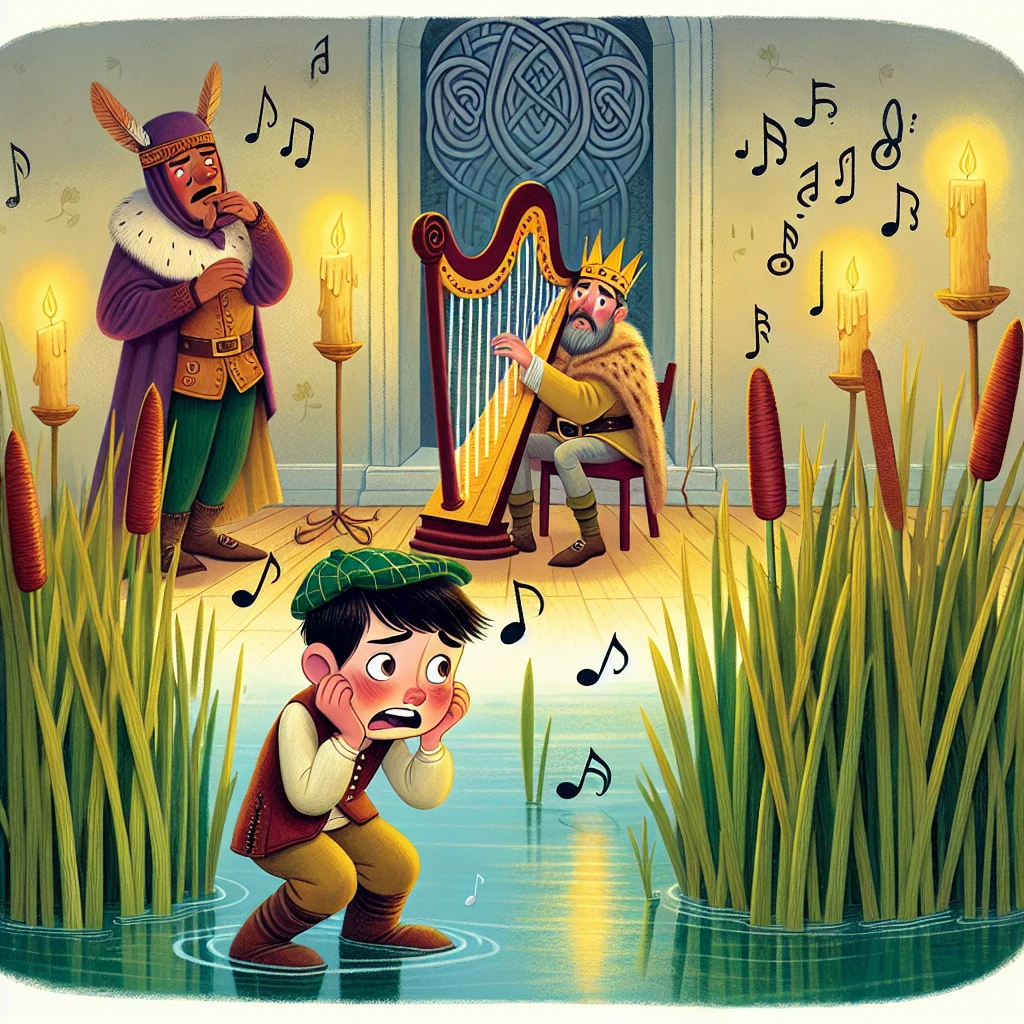

Weeks passed. The king called for music, as kings do when they have eaten too much and want to make the air carry their thoughts. A harp was made for the feast, its soundboard from the very reeds that had drunk Donnchadh’s secret. When the harper plucked, the hall brightened.

But the tune that came was not the tune he had tuned. From the strings poured a lively jig that turned into a chant, and the chant into words:

“The king, the king, the king—has ears like a horse! Under the velvet cap, oh of course, of course!”

The court went still. The king’s hand hovered over his cap as if the cap might fly away. Donnchadh tried to sink into the floor. The harper’s fingers froze and then, because he was a professional, kept playing.

A king may rage when his soldiers fail him; when music fails him, he must think. The king thought. Then he laughed, once, the sound a nail makes when it finally comes free of a board.

“Very well,” he said, and stood. He lifted the cap. The ears rose, proud as banners. Gasps fluttered like pigeons around the hall; then the pigeons settled.

“My ears are my ears,” said the king. “I have hunted with them, ruled with them, and heard good counsel with them. It seems they will be heard whether I speak of them or not. So let it be. I set no man’s tongue in irons today.”

He turned to Donnchadh. “As for you—next time, whisper to a tree. Reeds are musical by nature.”

Laughter shook the hall—the good laughter that tightens no throat. The harper, relieved, composed a better song on the spot.

After that, the king’s cap sat more lightly, and sometimes not at all. Children, being resilient, drew him with crowns and long ears and thought it a fine thing. The barber slept like a beast after winter.

And if a secret must be told, it is best told to something that knows how to keep time and tune—granite, perhaps, or the kind of friend who is more bedrock than bog.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus