The Birth and Taboos of Conaire Mór

legend by: Traditional Irish

Source: Irish Medieval Literature

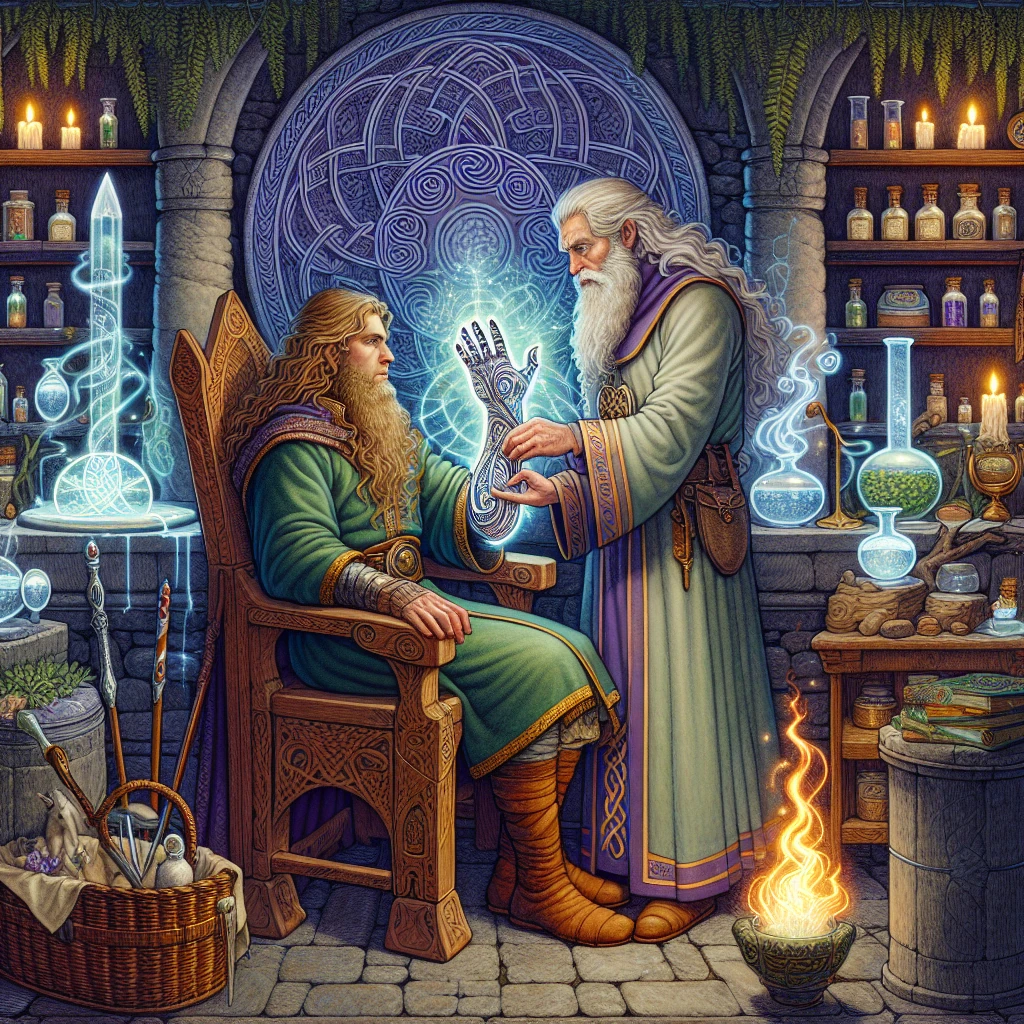

In the ancient annals of Ireland, few kings were as blessed at birth and as cursed by fate as Conaire Mór, whose story reveals the terrible burden that comes with divine kingship and the tragic consequences of breaking sacred taboos. His tale is one of supernatural birth, mystical kingship, and the inexorable working of destiny that even the greatest of kings cannot escape.

The Divine Conception

The story begins not with Conaire himself, but with his mother, Mess Búachalla, whose own birth was marked by wonder and mystery. She was the daughter of Étain and Cormac, king of Ulster, but her conception came about through the intervention of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the divine race that ruled Ireland before mortal men.

Mess Búachalla was raised in secret, hidden away from the world in a house of glass that her foster-parents built for her protection. She was said to be the most beautiful woman in all of Ireland, with hair like spun gold and eyes like stars reflected in still water. But her beauty was not merely mortal—it carried within it the otherworldly radiance of the Sidhe.

One day, as Mess Búachalla sat alone in her glass house, a great bird came to her window. The creature was larger than any natural bird, with feathers that shimmered like oil on water and eyes that held the wisdom of ages. When it spoke to her in a voice like wind through ancient trees, she knew immediately that this was no ordinary creature.

“I am Nemglan of the Tuatha Dé Danann,” the bird said, “and you have been chosen to bear a son who will be the greatest king Ireland has ever known.”

Before Mess Búachalla could reply, the bird shed its feathered form and stood before her as a man of supernatural beauty, tall and radiant with otherworldly power. His hair was dark as midnight, his skin pale as moonlight, and when he moved, the very air around him seemed to shimmer with magic.

The Prophecy and the Birth

Nemglan spoke to Mess Búachalla of the child she would bear, revealing prophecies that would shape the destiny of Ireland itself.

“Your son will be called Conaire,” he said, “and he will rule with justice and wisdom greater than any mortal king. Through him, Ireland will know peace and prosperity such as it has never experienced.”

But even as he spoke of glory, Nemglan’s voice carried a note of sadness. “Yet know this, beloved: with great power comes great restriction. Your son will be bound by sacred taboos—geasa—that he must never break. These prohibitions will protect his kingdom and his people, but they will also be the instruments of his destiny.”

When Conaire was born, the very earth seemed to celebrate his arrival. The crops grew more abundantly that year, the cattle gave richer milk, and no war disturbed the peace of the land. The child himself was clearly marked by his divine heritage—he had his father’s dark hair and pale skin, but his eyes held depths that seemed to reflect otherworldly knowledge.

As he grew, it became clear that Conaire was no ordinary prince. He was stronger, swifter, and more intelligent than other children, and there was about him an aura of authority that made even grown warriors defer to his wishes. When he spoke, people listened; when he smiled, hearts were lightened; when he frowned, the bravest men felt uneasy.

The Path to Kingship

When Conaire reached manhood, the high kingship of Ireland became vacant through the death of the previous ruler. According to ancient custom, the new king would be chosen through a mystical process known as the “bull-sleep,” in which a specially selected druid would dream while consuming the flesh and blood of a sacred bull, and in his visions would see the face of the rightful king.

The druid chosen for this solemn ritual was Cathbad, the wisest and most powerful of all the learned men in Ireland. When he emerged from his prophetic sleep, his face was radiant with wonder and certainty.

“I have seen the new king,” he announced to the assembled nobles. “He is a young man of otherworldly beauty, with dark hair and pale skin, who even now drives his chariot toward Tara. Birds fly before him as heralds, and the very air around him shimmers with divine favor.”

Even as Cathbad spoke these words, the sound of chariot wheels could be heard approaching the royal fortress. The great gates opened, and Conaire drove through them in a vehicle that seemed to move without touching the ground. Before him flew a flock of birds so beautiful that they seemed to be made of living jewels, their song filling the air with melodies that touched the soul.

When the young prince stepped down from his chariot, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that this was the king foretold in the druid’s vision. The crown of Ireland was placed upon his head amid great rejoicing, and the land itself seemed to sigh with satisfaction at the rightness of the choice.

The Sacred Taboos

But before Conaire could fully assume his royal duties, he was summoned to a sacred grove where the druids of Ireland had gathered to reveal the geasa—the mystical taboos—that would govern his reign. These prohibitions were not arbitrary rules but sacred bonds that connected the king to the very life force of the land.

The chief druid, his voice heavy with the weight of prophecy, spoke the taboos that would bind Conaire throughout his reign:

“You shall not go right-hand-wise around Tara, nor left-hand-wise around Bregia. You shall not hunt the evil beasts of Cernae. You shall not stay abroad from Tara for more than nine nights. You shall not sleep in a house from which firelight can be seen after sunset and into which one can see from outside. No three reds shall go before you to the house of Red. You shall not allow a company of one woman or one man to enter your house after sunset. You shall not interfere in a quarrel between two of your servants.”

Each taboo was explained in terms of its connection to the mystical forces that would keep Ireland prosperous and peaceful under Conaire’s rule. They were not mere superstitions but sacred truths woven into the very fabric of reality by the gods themselves.

Conaire accepted these restrictions willingly, understanding that they were the price of his divine kingship. “I shall keep these geasa as faithfully as the sun keeps its course across the sky,” he swore, and all who heard him knew that he meant every word.

The Golden Age

For many years, Conaire’s reign justified every prophecy that had been made about him. Under his rule, Ireland experienced what came to be known as the “Time of Truth,” when justice flowed through the land like a clear river and peace settled over the realm like gentle rain.

No crimes were committed during Conaire’s reign, for his very presence seemed to inspire virtue in all who encountered him. The crops grew abundantly without need for human labor, the cattle multiplied without disease, and the people prospered without conflict. Even the weather obeyed the king’s will—rain fell when it was needed, sunshine warmed the earth when growth was required, and storms held back until their fury would do no harm.

Foreign visitors to Ireland during this time marveled at what they found. “It is as if this land exists in a perpetual springtime of the soul,” one chronicler wrote. “Every face we see is bright with contentment, every field green with abundance, every home filled with laughter and song.”

Conaire himself embodied the virtues he inspired in others. He was generous without being wasteful, firm without being cruel, wise without being proud. His court became a gathering place for the greatest poets, musicians, and scholars of the age, and his judgments were so fair and wise that people traveled from distant lands to seek his counsel.

The First Warning

But even in the midst of this golden age, there were subtle signs that the foundations of prosperity might not be as stable as they appeared. The first warning came through Conaire’s foster-brothers, a group of young nobles who had been raised alongside him but who possessed none of his divine nature.

Unlike Conaire, whose character had been shaped by his otherworldly heritage, his foster-brothers were purely mortal, with all the flaws and weaknesses that mortality entails. As they grew older, they became increasingly resentful of the restrictions that governed their foster-brother’s life and frustrated by what they saw as the unfair advantages of his divine kingship.

“Why should you be bound by these foolish taboos?” they argued. “You are the king of Ireland! These ancient prohibitions were made by dead druids for dead kings. Surely your power is great enough to transcend such petty restrictions.”

Conaire listened to their arguments with growing unease, for he could see the logic in their words even as he felt the danger in them. The taboos had protected him and his kingdom for so long that their weight had become almost invisible, like the weight of air that sustains life without being felt.

“The geasa are not chains,” he explained to his foster-brothers. “They are the very foundations upon which my kingship rests. To break them would be like a man cutting away the earth beneath his own feet.”

But his words could not still the growing discontent among those closest to him, and Conaire began to sense that the perfect harmony of his reign was beginning to develop cracks that might one day widen into chasms.

The Growing Pressure

As the years passed, the pressure to break his taboos grew stronger. Diplomatic necessity began to conflict with sacred prohibition. When important allies invited him to feasts that would require him to sleep away from Tara for more than nine nights, Conaire found himself caught between honoring his sacred bonds and maintaining the political relationships that kept Ireland peaceful.

His advisors, well-meaning but lacking understanding of the mystical forces at work, began to urge him toward pragmatism. “Surely the gods will understand if you bend these rules for the good of the kingdom,” they said. “What harm could come from a single exception made for the highest purposes?”

Even more troubling were the dreams that began to visit Conaire during this period. In these visions, he saw a great darkness approaching Ireland from across the sea—foreign invaders with iron weapons and hearts full of greed, seeking to destroy everything he had built. The dreams suggested that only by taking certain actions—actions that would require breaking his taboos—could this disaster be averted.

Night after night, Conaire would wake from these prophetic dreams in a cold sweat, torn between his duty to preserve his sacred bonds and his responsibility to protect his people from the terrible future he had seen. The weight of kingship, which had once sat lightly on his shoulders, began to feel like a crushing burden.

The Moment of Choice

The crisis came when Conaire’s foster-brothers were discovered engaged in acts of piracy and murder along the Irish coast. When they were brought before the king for judgment, they threw themselves upon his mercy, pleading with him to use his royal authority to pardon their crimes.

“We did this for you,” they claimed. “We sought to gather wealth and weapons to strengthen your kingdom against the threats we see gathering on the horizon. If you punish us for serving your interests, what loyal follower will ever again take risks on your behalf?”

The truth was more complex and more troubling. Conaire’s foster-brothers had indeed committed crimes, but they had been driven to it partly by their frustration with the limitations that their association with the king placed upon them. They could not pursue wealth and glory through normal means without potentially compromising Conaire’s taboos, so they had turned to more desperate measures.

Faced with this dilemma, Conaire found himself confronting the fundamental contradiction of his position. To uphold perfect justice, he would have to condemn his foster-brothers to death or exile. But to do so would be to abandon those who had been closest to him since childhood, and might drive them to even more desperate acts.

After much agonizing deliberation, Conaire chose a middle path that satisfied neither justice nor mercy completely. He pardoned his foster-brothers but exiled them from Ireland, hoping that this compromise would protect both his sacred obligations and his personal relationships.

The First Break

This decision, well-intentioned though it was, marked the beginning of the end of Conaire’s golden age. The very act of compromising between sacred duty and personal loyalty weakened the mystical bonds that held his kingdom in perfect harmony. The land itself seemed to sense this weakening—crops that year were merely good rather than miraculous, and there were reports of minor crimes and disputes in distant parts of the realm.

More seriously, Conaire’s exiled foster-brothers did not accept their punishment with grace. Instead of seeking redemption in foreign lands, they gathered around themselves a band of outcasts and criminals, forming a war-band that began to threaten the peace of Ireland from beyond its borders.

When news reached Conaire that his foster-brothers had allied themselves with foreign raiders and were planning an attack on the Irish coast, he faced the most terrible choice of his reign. To defend his people effectively, he would need to pursue his enemies beyond Ireland’s borders—but to do so would require breaking his taboo against staying away from Tara for more than nine nights.

The weight of this dilemma pressed upon Conaire like a physical burden. His druids warned him that breaking even one of his taboos would begin a cascade of consequences that could not be stopped. His warriors argued that the kingdom’s survival took precedence over ancient prohibitions.

“A king’s first duty is to his people,” his champion declared. “If the gods gave you power, surely they intended you to use it to protect those who depend upon you.”

The Fatal Decision

In the end, it was love for his people rather than pride or ambition that led Conaire to make the fatal decision. When his scouts reported that his foster-brothers’ warband was preparing to attack a defenseless coastal village, he could not stand idle while innocent people suffered for his sake.

“I will not let others pay the price for my conflicts,” he declared. “If the gods demand my destruction as the price of protecting my people, then I accept that fate.”

Against the desperate pleas of his druids, Conaire led his army beyond Ireland’s borders in pursuit of his foster-brothers. The very air seemed to thicken with foreboding as he crossed the sacred boundaries that had protected him, and those who were sensitive to such things reported feeling a great sorrow settling over the land.

The pursuit lasted for more than nine nights, and with each day that passed, Conaire could feel the mystical protections that had surrounded him growing weaker. His divine strength began to ebb, his otherworldly wisdom became clouded, and the certainty that had always guided his decisions gave way to doubt and confusion.

When he finally confronted his foster-brothers on a windswept battlefield beside the sea, the man who faced them was still a king, but no longer a divine one. The sacred bonds that had made him more than mortal had been broken, and with them, the golden age of Ireland had come to an end.

The Prophecy Fulfilled

The battle itself was fierce but brief. Conaire’s forces, though still loyal and brave, no longer fought with the supernatural coordination that had made them invincible. His foster-brothers, empowered by their alliance with otherworldly forces of chaos and destruction, proved more formidable than anyone had expected.

In the end, it was not martial skill but the inevitable working of fate that determined the outcome. As the sun set on that distant shore, Conaire fell beneath the weapons of those he had once called brothers, his divine blood soaking into foreign soil far from the sacred earth of Tara.

With the king’s death, the mystical protections that had kept Ireland in perfect harmony collapsed like a house of cards. The golden age ended not with a gradual decline but with sudden, catastrophic finality. Wars broke out across the land, crimes returned to the realm, and the supernatural abundance that had marked Conaire’s reign vanished as if it had never been.

The Legacy of Taboos

The story of Conaire Mór became one of the most important teaching tales in Irish tradition, illustrating the complex relationship between power and responsibility, between divine favor and human limitation. It showed that even the greatest gifts come with proportional restrictions, and that the breaking of sacred bonds, however well-intentioned, carries consequences that extend far beyond the individual.

But the tale also honored the tragic nobility of Conaire’s choice. He was not destroyed by pride or greed, but by love for his people and the impossible burden of divine kingship. His story suggests that sometimes the greatest heroes are those who accept destruction rather than allow others to suffer for their sake.

In later years, when the bards sang of Conaire Mór, they would always emphasize both the glory of his reign and the tragedy of its ending, reminding their listeners that in the world of gods and mortals, even the most perfect harmony contains within itself the seeds of its own destruction. The tale stands as a permanent reminder that with great power comes not just great responsibility, but great vulnerability—and that the price of divine favor may be higher than any mortal, however noble, can ultimately bear.

Through Conaire’s story, the ancient Irish explored some of their deepest questions about leadership, duty, and the relationship between human will and divine law. His reign represented the highest possibility of mortal kingship, while his fall demonstrated the tragic consequences that await those who, however reluctantly, transgress the sacred boundaries that define their place in the cosmic order.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus