Wise Folks

Story by: Brothers Grimm

Source: Kinder- und Hausmärchen

In a valley surrounded by green hills and babbling streams, there stood a village whose residents were absolutely convinced that they were the wisest people in all the world. The village was called Schönberg, and its inhabitants took great pride in their reputation for intelligence and clever thinking.

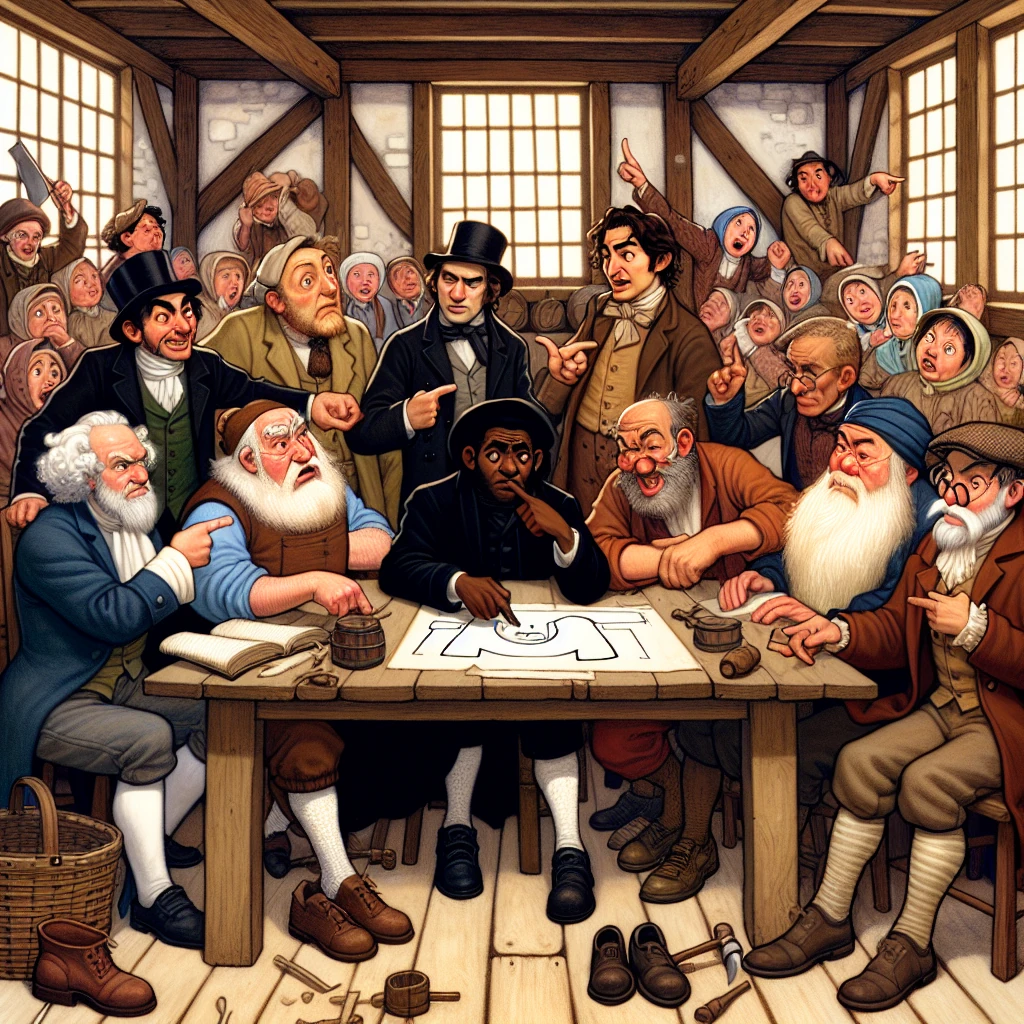

The people of Schönberg had appointed themselves a Council of Wise Folks, consisting of seven of the most pompous and self-important residents of the village. These seven individuals—the baker, the blacksmith, the tailor, the miller, the carpenter, the shoemaker, and the innkeeper—met every week to discuss important matters and make decisions for the good of the community.

The problem was that while the Wise Folks of Schönberg were very good at appearing intelligent and using impressive-sounding words, they were actually quite lacking in common sense and practical wisdom.

One day, a traveling merchant passed through Schönberg and happened to observe one of the Council meetings. He watched in amazement as the seven Wise Folks engaged in a heated debate about the best way to carry water from the village well to the town square.

“Clearly,” declared the baker pompously, “the most efficient method would be to construct a series of buckets connected by ropes, allowing us to transport the water in a continuous chain.”

“Nonsense!” replied the blacksmith. “The logical approach would be to build a special cart with wheels made of sponges, so that the water would be absorbed and transported automatically.”

The tailor adjusted his spectacles importantly. “You are both missing the obvious solution. We should train the village dogs to carry small containers of water in their mouths, creating a natural delivery system.”

The merchant shook his head in disbelief and quietly continued on his way, leaving the Wise Folks to their elaborate discussions about a problem that could easily be solved with simple buckets and common sense.

Word of this incident spread to neighboring villages, and soon people began traveling to Schönberg specifically to observe the amusing deliberations of the supposedly wise council. These visitors were rarely disappointed by what they witnessed.

During one memorable meeting, the Council spent an entire afternoon debating how to prevent the village church bell from getting wet during rainstorms.

“I propose we construct a large umbrella to hold over the bell tower,” suggested the miller seriously.

“That’s impractical,” countered the carpenter. “We should obviously build a small roof for the bell itself, positioned just above it to deflect the rain.”

The shoemaker stroked his beard thoughtfully. “Why don’t we simply move the bell indoors during bad weather? It would be much simpler.”

“And how exactly,” asked the innkeeper, “would we move a bell that weighs several hundred pounds every time it looks like rain?”

This question stumped the shoemaker, who sat down to think more carefully about his suggestion.

Eventually, they decided to hire a man whose sole job would be to stand next to the bell during rainstorms and hold a large piece of canvas over it. The fact that the bell had been hanging in the same tower for over a hundred years without suffering any damage from rain never occurred to any of them.

Another famous incident involved the Council’s decision to solve the problem of their village pond freezing over in winter. They were concerned that if the ice became too thick, it might harm the fish living in the pond.

“Clearly,” announced the baker, “we need to keep the water moving to prevent it from freezing. I suggest we hire someone to stir the pond continuously throughout the winter months.”

“But how would one person stir an entire pond?” asked the tailor.

“With a very large spoon, obviously,” the baker replied, as if this were the most natural thing in the world.

The blacksmith had a different idea. “We should heat large stones in our forges and throw them into the pond to keep the water warm.”

“That might work,” agreed the miller, “but we would need a great many stones, and the heating would be very expensive.”

After much debate, they settled on a compromise solution: they would place several large cooking pots around the edge of the pond and build fires under them to heat the water, which would then somehow warm the entire pond through proximity.

When winter came, they implemented this plan exactly as discussed. Of course, the small fires around the pond’s edge had no effect whatsoever on the temperature of the water, and the pond froze solid just as it had every winter for centuries.

The Wise Folks were puzzled by this failure and spent many meetings analyzing what had gone wrong. They concluded that they simply hadn’t used enough pots.

Perhaps the most famous example of their wisdom occurred when they decided to address the problem of the village’s narrow main street. Loaded carts and wagons often had difficulty passing each other, causing traffic jams and delays.

“The solution is obvious,” declared the carpenter. “We need to widen the street.”

“But how do we widen a street that already has buildings on both sides?” asked the shoemaker.

The carpenter had clearly thought this through. “We simply move all the buildings back by ten feet. It’s perfectly logical.”

“And where,” inquired the innkeeper, “would we put the buildings while we’re moving them?”

This question launched an extended debate about temporary building storage, which eventually led to a discussion about whether buildings could be folded up like tents for easier transportation.

In the end, they decided to solve the narrow street problem by posting signs at both ends warning drivers to “drive more narrowly.” They were very proud of this clever solution.

News of these incidents eventually reached the attention of the regional governor, who decided to visit Schönberg to observe the famous Wise Folks in action. He arrived on a day when the Council was addressing what they considered to be their most serious challenge yet.

A traveling scholar had visited the village and mentioned that the earth was round, not flat. This information had thrown the Wise Folks into complete confusion, as they couldn’t understand how people on the bottom of a round earth could avoid falling off.

“Clearly,” the tailor was explaining when the governor arrived, “if the earth is round, then people in some places must be hanging upside down. We need to send aid to these unfortunate souls.”

“But how would we get aid to people who are upside down?” asked the baker.

“We would obviously have to send it upward,” replied the tailor, as if this were perfectly logical.

The miller nodded sagely. “I suggest we tie messages to birds and train them to fly toward the sky to reach the upside-down people.”

The governor listened to this discussion with growing amazement. Finally, he could contain himself no longer.

“Excuse me,” he interrupted politely, “but may I ask what problem you are trying to solve?”

The seven Wise Folks turned to look at him with surprise.

“We are addressing the serious issue of people who live upside down on the bottom of the round earth,” the carpenter explained patiently, as if speaking to a child.

“I see,” said the governor. “And it has never occurred to you that perhaps these people don’t feel upside down because, from their perspective, they are right side up?”

The Wise Folks stared at him blankly. This concept was clearly beyond their understanding.

“That’s impossible,” declared the blacksmith. “Up is up and down is down. You can’t change that just by standing in a different place.”

The governor realized that trying to explain relative perspective to the Wise Folks would be hopeless. Instead, he decided to test their wisdom with a simple question.

“Tell me,” he said, “if a farmer has seventeen sheep and all but nine die, how many sheep does he have left?”

The Wise Folks immediately launched into an intense discussion about this mathematical challenge.

“Seventeen minus nine equals eight,” calculated the baker.

“No, no,” corrected the tailor. “The question asks about all but nine dying, which means nine survived. So the answer is nine.”

“But what about the ones that died?” asked the miller. “Don’t they count?”

“Dead sheep don’t count as sheep,” declared the shoemaker. “They count as mutton.”

The governor waited patiently for them to reach a conclusion, but after twenty minutes of increasingly convoluted debate, he realized they were no closer to the correct answer than when they had started.

“The answer,” he said gently, “is nine. If all but nine die, then nine remain alive.”

The Wise Folks looked at him with newfound respect.

“How did you figure that out so quickly?” asked the innkeeper with obvious admiration.

From that day forward, the governor became something of a legend in Schönberg. The Wise Folks frequently told visitors about the incredibly intelligent man who had solved their sheep problem in mere moments.

However, they never seemed to learn from his example. They continued to approach every problem with the same elaborate overthinking and lack of common sense that had made them famous throughout the region.

Eventually, the people of neighboring villages began to appreciate the Wise Folks of Schönberg for what they truly were—not examples of wisdom, but wonderful sources of entertainment and reminders that intelligence and education are not the same thing as wisdom and common sense.

The Wise Folks themselves remained blissfully unaware of their reputation. They continued to pride themselves on their intellectual discussions and clever solutions, never suspecting that visitors came to their Council meetings not to learn from their wisdom, but to laugh at their folly.

And perhaps, in their own way, the Wise Folks of Schönberg did provide a valuable service to the world. They reminded everyone who met them that true wisdom lies not in using impressive words or complicated theories, but in applying practical common sense to everyday problems.

The village of Schönberg still exists today, and travelers still visit to hear stories about the famous Wise Folks. The current residents of the village, who are perfectly normal and sensible people, enjoy sharing these tales as humorous reminders of the importance of thinking before acting and of the difference between appearing wise and actually being wise.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus