The Story of the Barber's Six Brothers

Original Qissat al-Ikhwa al-Sitta lil-Hallaq

Story by: Arabian Folk Tales

Source: One Thousand and One Nights

In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the Merciful, I shall tell you the tale of the Barber’s Six Brothers, a story that reveals the diverse ways in which human folly can lead to misfortune, and how pride, greed, and self-deception can transform promising lives into cautionary tales.

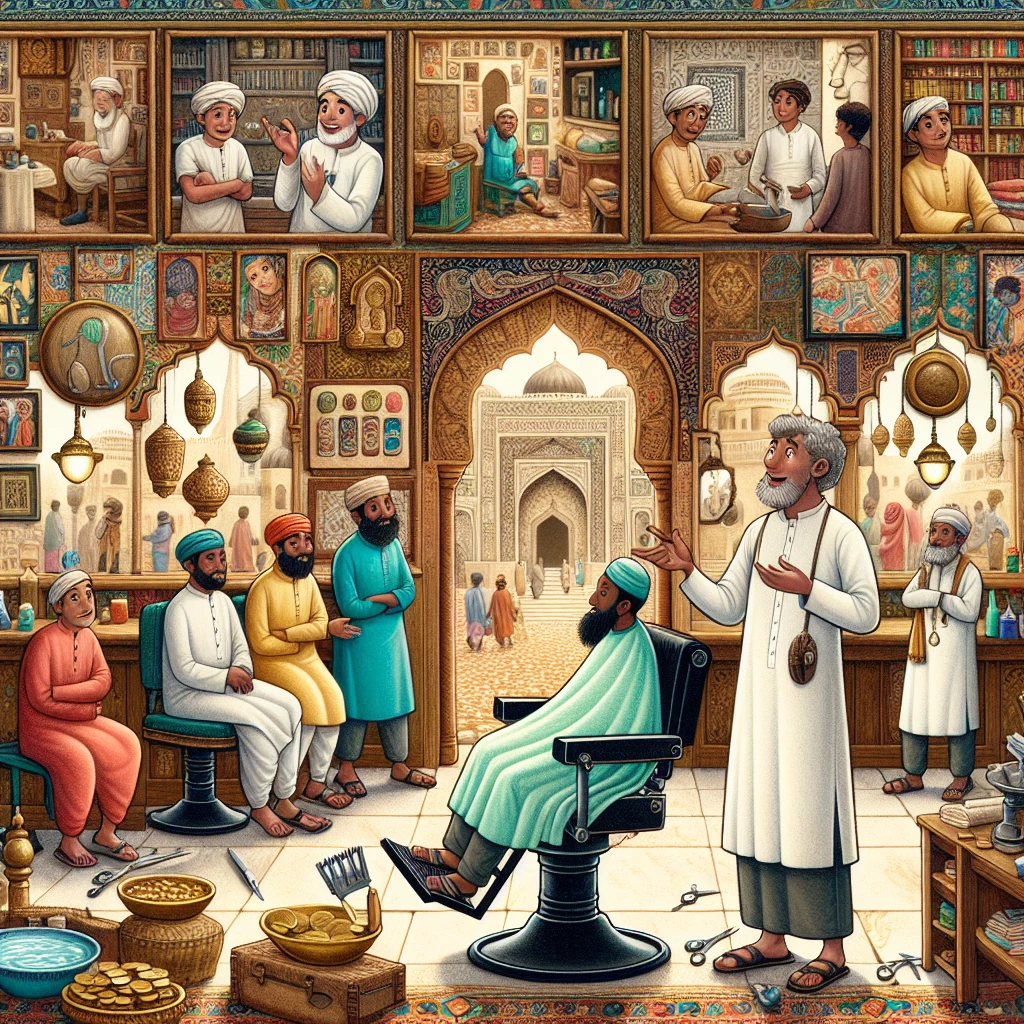

In the great city of Baghdad, during the reign of the Commander of the Faithful Harun al-Rashid, there lived a barber whose skill with razor and scissors was matched only by his extraordinary talent for conversation. This barber, whose name was Abu al-Salam al-Kalawi, possessed such a gift for speech that customers often came to his shop not merely for grooming but for the entertainment of his endless stories and observations about human nature.

Abu al-Salam had six brothers, each of whom had chosen a different path in life, and each of whom had encountered misfortunes that were both tragic and instructive. The barber delighted in telling their stories to his customers, partly from genuine affection for his siblings, partly from his natural love of storytelling, and partly as moral lessons about the consequences of various character flaws.

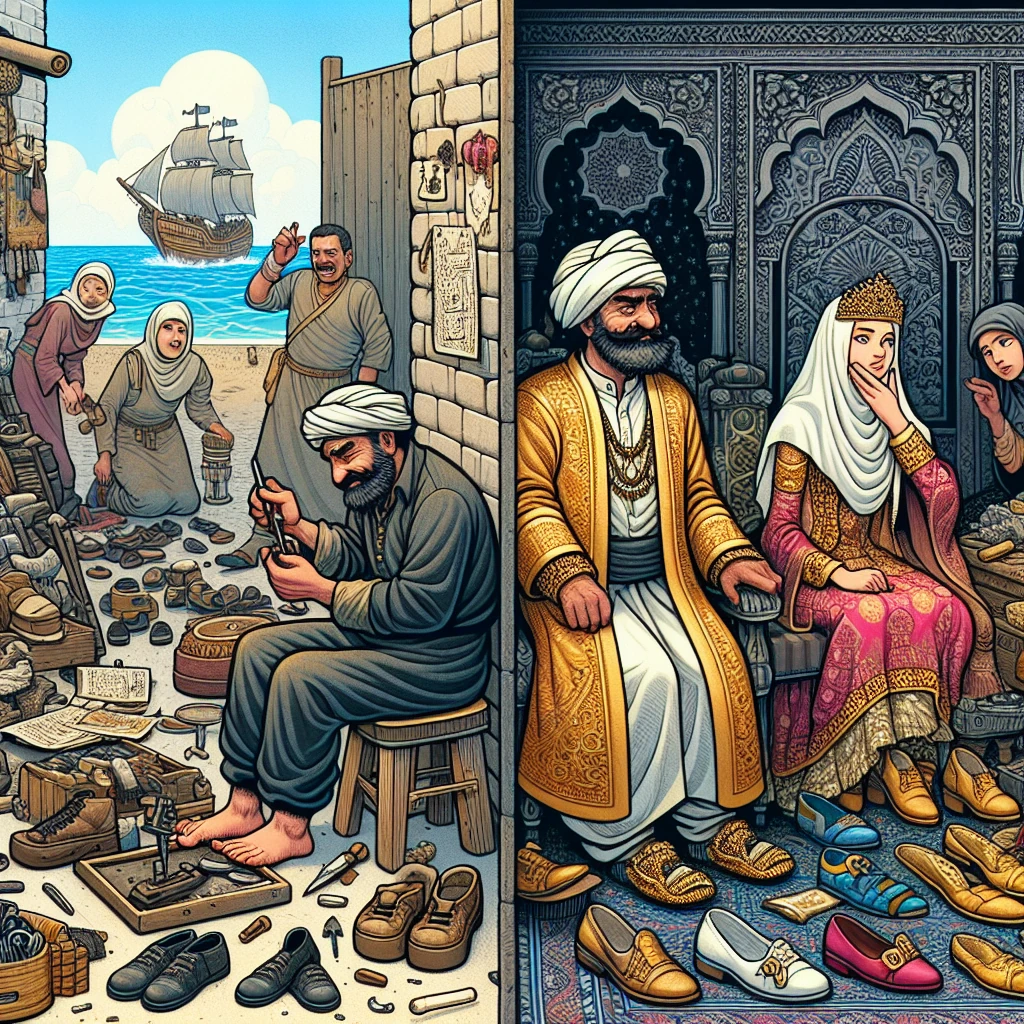

“My first brother,” Abu al-Salam would begin, adjusting his customer’s head to catch the best light while sharpening his razor, “was named Bakbak al-Ahwal, which means ‘The Stammerer,’ though his speech impediment was the least of his problems. Bakbak was a tailor by trade, and initially quite successful at his craft. His stitching was precise, his measurements accurate, and his prices fair.”

As he began to trim his customer’s beard with practiced precision, the barber continued: “However, my brother Bakbak suffered from a terrible weakness—he was convinced that every wealthy person who entered his shop was secretly in love with him. This delusion led him to misinterpret ordinary business interactions as romantic overtures, with consequences that were both embarrassing and destructive.”

The barber paused in his work to gesture dramatically: “One day, a wealthy merchant’s wife came to Bakbak’s shop to commission a robe for her husband. She was veiled, as is proper for virtuous women, and spoke only of measurements, fabric choices, and payment terms. But Bakbak, in his vanity, convinced himself that her professional courtesy was actually passionate admiration poorly concealed.”

“When the lady returned the following week to collect the finished garment, Bakbak presented her not only with the requested robe but also with a love poem he had composed, declaring his devotion and begging her to elope with him to distant lands where they could live as husband and wife.”

The customer, thoroughly absorbed in the story, asked what happened next.

“The lady was so offended by this presumptuous behavior that she reported Bakbak to her husband, who came to the shop with several armed servants and administered such a beating to my poor brother that he was confined to bed for three months. Moreover, word of his inappropriate conduct spread throughout the merchants’ quarter, and his business was ruined because no respectable family would trust him with commissions.”

The barber’s second tale began as he moved to trim his customer’s mustache: “My second brother, Bakkar al-Hakim, was known as ‘The Wise One,’ though events proved this title to be entirely undeserved. Bakkar was a cook in the household of a wealthy judge, and he prided himself on his culinary skills and his supposed understanding of human nature.”

“Bakkar’s downfall came from his habit of eavesdropping on his master’s private conversations and then offering unsolicited advice based on what he had overheard. He convinced himself that his position in the kitchen gave him special insights into the family’s affairs, and that his suggestions would be welcomed as evidence of his loyalty and intelligence.”

“One evening, Bakkar overheard his master discussing a complex legal case with a colleague. The next morning, he approached the judge and offered detailed recommendations about how the case should be decided, demonstrating that he had been listening to private conversations and presuming to advise a learned jurist about matters of law.”

“The judge was so angry at this breach of trust and display of arrogance that he not only dismissed Bakkar from his service but also ensured that no other household in the city would employ him. My brother was forced to become a street vendor, selling simple foods to laborers and beggars, a dramatic fall from his former position.”

As he applied scented oil to his customer’s beard, Abu al-Salam introduced his third brother’s story: “Bakbaz al-Nazal was my third brother, and his name meant ‘The Guest’ because he had an unfortunate habit of inviting himself to social occasions where he was not wanted. Bakbaz worked as a street musician, and he possessed genuine talent with the oud and a pleasant singing voice.”

“However, Bakbaz suffered from the delusion that his musical abilities entitled him to the same respect and welcome accorded to court entertainers. He would arrive uninvited at weddings, festivals, and private celebrations, assuming that his performance would be so appreciated that his presumption would be forgiven.”

“The incident that ended his career occurred at the wedding of a prominent merchant’s daughter. Bakbaz appeared at the celebration without invitation and began performing in the courtyard, expecting to be welcomed and rewarded. Instead, the bride’s family was offended by his intrusion on their private ceremony, and the male guests threw him into the fountain and broke his oud over his head.”

“The humiliation was so complete that Bakbaz lost confidence in his abilities entirely. He sold his remaining instruments and became a porter, carrying goods for merchants who had once enjoyed his music but now regarded him as a cautionary example of artistic pretension.”

The fourth tale emerged as the barber began cleaning his tools: “My fourth brother, Alquz al-Barbari, was called ‘The Berber’ because of his origins, though he had lived in Baghdad since childhood. Alquz was a butcher who operated a small but profitable shop in the meat market, and for many years he conducted his business with honesty and skill.”

“Alquz’s problems began when he became obsessed with the idea that his customers were trying to cheat him. He started weighing every purchase multiple times, examining every coin for signs of counterfeiting, and accusing honest customers of attempting various forms of fraud.”

“His suspicions became so extreme that he would spend entire days re-counting his money, re-weighing his meat, and investigating imaginary conspiracies against his business. His behavior became so erratic that customers began avoiding his shop, preferring to buy their meat from vendors who treated them with basic courtesy and trust.”

“The final catastrophe occurred when Alquz accused the chief of the market police of trying to pay for meat with counterfeit coins. This accusation was not only false but also deeply insulting to an honest official. Alquz was arrested, his shop was confiscated, and he was banned from working in any food-related business in the city.”

As he prepared to shave his customer’s neck, the barber continued with his fifth brother’s misfortune: “Fayyad al-Mahdi was my fifth brother, and his name meant ‘The Guide’ because he worked as a tour guide for foreign merchants visiting Baghdad. Fayyad possessed extensive knowledge of the city’s history, its markets, and its notable buildings, and initially he was quite successful in his profession.”

“However, Fayyad developed an irresistible urge to embellish his knowledge with fabricated details. If he didn’t know the actual history of a building, he would invent elaborate stories about its construction. If he was uncertain about the price of goods in a particular market, he would quote figures that sounded impressive but bore no relation to reality.”

“At first, his foreign clients were entertained by these creative additions to their tours. But eventually, several merchants who had relied on Fayyad’s information found themselves embarrassed in business negotiations or misled about the value of their purchases.”

“When word of Fayyad’s unreliability spread among the foreign trading community, his reputation was destroyed. No merchant would trust him as a guide, and he was forced to work as a street sweeper, using his intimate knowledge of Baghdad’s layout to clean the very streets he had once guided visitors through with such fictional authority.”

Finally, as he applied a hot towel to his customer’s face, Abu al-Salam told the story of his sixth brother: “Shakashik al-Tayyar was my youngest brother, and his nickname meant ‘The Flyer’ because of his habit of leaping from rooftop to rooftop as he pursued his profession as a thief. Unlike my other brothers, Shakashik was quite successful at his chosen career, despite its obviously questionable morality.”

“Shakashik’s downfall came not from incompetence but from overconfidence. After years of successful burglaries, he began to believe that he was invincible and that no security measures could prevent him from stealing whatever caught his eye.”

“His fatal mistake was attempting to rob the house of a retired military commander who had spent decades fighting on the empire’s frontiers. This veteran had installed security devices learned from various enemies and allies, creating a house that was essentially a trap for unwary intruders.”

“When Shakashik entered the house, he triggered a mechanism that trapped him in a room with no exits except the window through which he had entered. The window was positioned so that anyone trying to escape would fall directly into the courtyard, where the owner waited with a sword and several loyal servants.”

“Shakashik was captured, tried, and sentenced to have his right hand cut off as punishment for theft. The loss of his hand ended his criminal career, but it also taught him the value of honest work. He became a mosque attendant, using his remaining hand to tend the lamps and clean the prayer rugs, finding in religious service a peace that had eluded him during his years of crime.”

As Abu al-Salam finished his customer’s shave and applied fragrant aftershave, he concluded his tales with a philosophical observation: “You see, honored customer, each of my brothers possessed genuine talents and abilities. Bakbak was an excellent tailor, Bakkar a skilled cook, Bakbaz a talented musician, Alquz an honest butcher, Fayyad a knowledgeable guide, and Shakashik a remarkably agile climber.”

“Their misfortunes did not arise from lack of ability but from character flaws that corrupted their talents and led them to make poor choices. Bakbak’s vanity, Bakkar’s presumption, Bakbaz’s arrogance, Alquz’s paranoia, Fayyad’s dishonesty, and Shakashik’s criminal ambition each transformed what could have been successful careers into cautionary tales.”

The customer, his grooming complete, paid the barber and asked whether any of the brothers had learned from their experiences and rebuilt their lives.

“An excellent question,” replied Abu al-Salam, beginning to clean his shop in preparation for the next customer. “Indeed, several of my brothers did find wisdom through suffering. Bakbaz eventually regained his confidence and now performs at modest celebrations where his music is genuinely welcomed. Alquz overcame his paranoia and works as an assistant to an honest butcher who appreciates his attention to detail.”

“Fayyad learned to value truth over entertainment and became a reliable clerk for a shipping merchant who needed accurate records rather than exciting stories. And Shakashik, as I mentioned, found spiritual peace in mosque service and often tells young men about the emptiness of criminal pursuits.”

“Only Bakbak and Bakkar failed to learn from their mistakes. Bakbak continues to believe that every woman who speaks to him is secretly in love, and he now works as a street sweeper while composing terrible poetry to female passers-by. Bakkar still offers unsolicited advice to anyone who will listen, and he supplements his food vending by dispensing unwanted wisdom to his customers.”

As another customer entered the shop, Abu al-Salam prepared to begin both a new grooming session and perhaps another round of storytelling. “The moral of my brothers’ tales,” he announced to both the departing and arriving customers, “is that talent without character is like a sharp knife in the hands of a child—dangerous to the wielder and potentially harmful to others.”

“Success in any profession requires not only skill but also humility, honesty, and respect for others. My brothers who learned these lessons found happiness even in reduced circumstances, while those who clung to their character flaws remained miserable despite their abilities.”

The new customer, intrigued by this introduction, settled into the barber’s chair and requested not only a shave and haircut but also more stories about the consequences of various human failings. Abu al-Salam smiled with satisfaction and began to sharpen his razor while mentally reviewing his extensive collection of moral tales.

And so the barber’s shop continued to serve as both a place of grooming and a center of moral instruction, where the fates of six brothers provided endless material for reflection on the relationship between character and destiny. Customers left not only better groomed but also better informed about the pitfalls that await those who allow pride, greed, or dishonesty to corrupt their natural talents.

The tales of the barber’s six brothers became part of Baghdad’s oral tradition, told and retold in coffee houses and private gatherings as examples of how individual character flaws can transform promising lives into cautionary examples. Parents used these stories to teach their children about the importance of humility and honesty, while merchants and craftsmen found in them warnings about the professional dangers of arrogance and deception.

Years later, when Abu al-Salam himself grew old and could no longer handle razor and scissors with his former precision, he became a professional storyteller, traveling throughout the Islamic world and sharing the moral lessons he had learned from observing his brothers’ mistakes. His tales were recorded by scribes and eventually became part of the great collection of stories that preserved the wisdom and folly of human experience for future generations.

Thus the misfortunes of six brothers were transformed through the art of storytelling into a form of immortality, their individual failures becoming collective wisdom that would guide and warn countless future listeners about the eternal human struggle between talent and character, ambition and wisdom, pride and humility.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus