The Story of Ma'aruf the Cobbler

Original Qissat Ma'ruf al-Iskafi

Story by: Arabian Folk Tales

Source: One Thousand and One Nights

In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the Merciful, I shall tell you the remarkable tale of Ma’aruf the Cobbler, whose extraordinary journey from poverty to wealth, from misery to happiness, demonstrates how divine providence can transform the humblest life when suffering is endured with patience and good deeds are performed with sincerity.

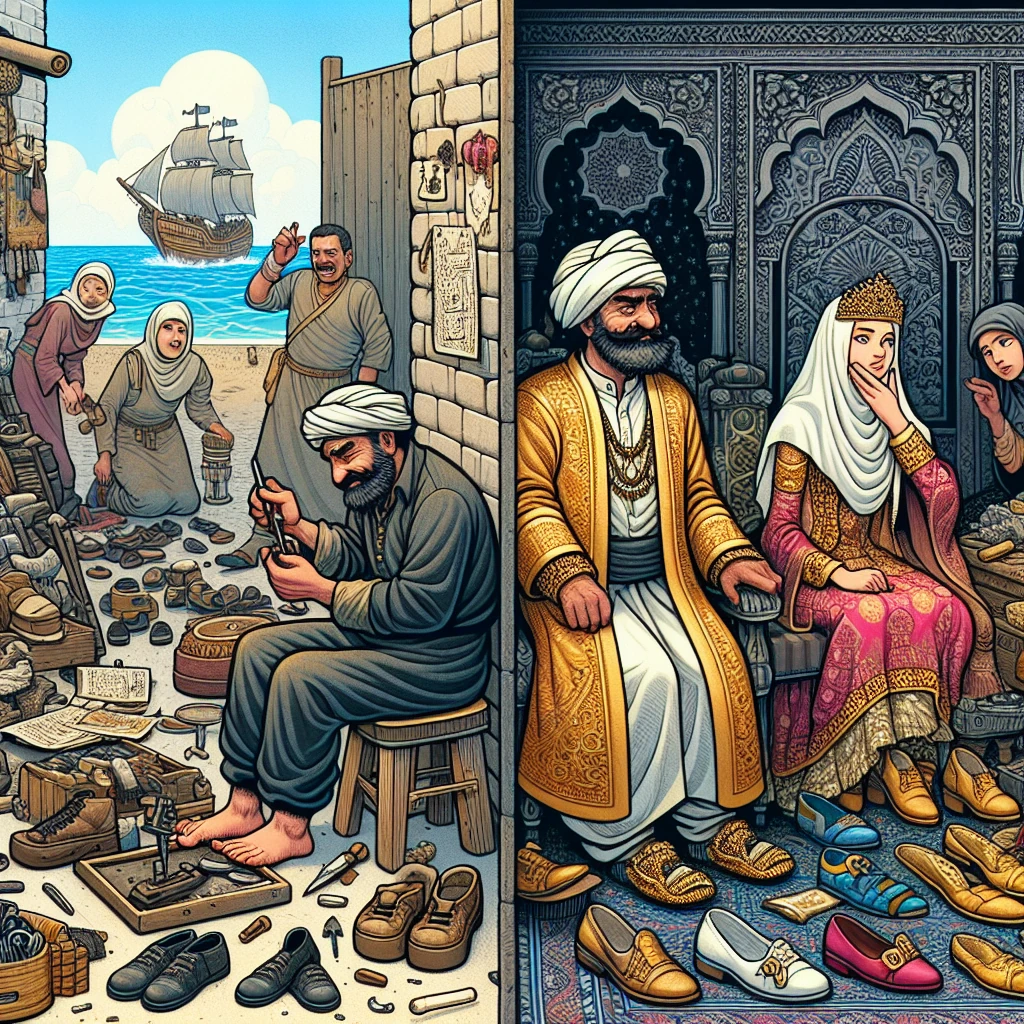

In the great city of Cairo, during the reign of the illustrious Sultan al-Zahir Baybars, there lived in one of the poorest quarters a cobbler named Ma’aruf whose skill with leather and thread was exceeded only by the misery of his domestic circumstances. Ma’aruf was a man of gentle nature and honest character, but he had made the unfortunate decision in his youth to marry a woman whose beauty had blinded him to her numerous character defects.

Fatimah, for such was his wife’s name, possessed a tongue sharper than any blade in Damascus and a temper more volatile than the desert winds. From dawn until midnight, she subjected her husband to a constant stream of complaints, criticisms, and demands that would have tried the patience of the Prophet Job himself. Nothing Ma’aruf did ever satisfied her expectations, and no amount of labor on his part could generate enough income to meet her extravagant desires.

“Ma’aruf, you worthless excuse for a man!” she would shriek every morning as he prepared to open his modest shop. “Look at the wives of other craftsmen—they wear silk and jewelry while I am forced to dress in rags! They eat meat and sweets while I subsist on bread and onions! When will you stop being such a failure and earn the money to support your wife properly?”

Ma’aruf, who worked from sunrise to sunset repairing shoes for customers who often could barely afford to pay him, would endure these tirades with patient resignation. “Wife,” he would reply gently, “I labor as hard as any man in Cairo. If Allah blesses us with prosperity, we shall live better. Until then, we must be grateful for what we have and trust in divine providence.”

But Fatimah’s response to such philosophical acceptance was only to increase the volume and vehemence of her complaints. She would compare Ma’aruf unfavorably to every other husband in the neighborhood, speculate loudly about his lack of ambition and intelligence, and threaten to leave him for a man who could provide the luxuries she believed she deserved.

This domestic torment continued for years, with Ma’aruf growing ever more thin and careworn while his wife seemed to grow more beautiful and more demanding with each passing season. The neighbors, who could hear Fatimah’s voice through the thin walls of their modest house, began to pity Ma’aruf and wonder how any man could endure such constant abuse without either fleeing or retaliating.

The crisis that would change Ma’aruf’s life forever began on a particularly hot day in the month of Ramadan, when his wife’s craving for sweets overcame what little restraint she normally exercised. As Ma’aruf returned home after a day of earning barely enough to buy bread for their evening meal, Fatimah greeted him with a demand that seemed designed to test the limits of possibility.

“Husband,” she announced with the imperious tone she reserved for her most unreasonable requests, “I desire kunafah—that delicious pastry made with cheese and honey that is sold in the wealthy quarters of the city. You will go immediately and purchase some for me to break my fast.”

Ma’aruf stared at his wife in amazement. Kunafah was a luxury that cost more than he earned in a week, and their household budget barely covered the basic necessities of survival. “My dear wife,” he replied as gently as possible, “we do not have money for such expensive sweets. Perhaps you would accept some dates or figs instead?”

Fatimah’s reaction to this reasonable suggestion was explosive. She began screaming accusations that echoed through the entire neighborhood—that Ma’aruf was deliberately starving her, that he spent his earnings on personal pleasures while denying her basic needs, and that she would report his cruelty to the magistrates if he did not immediately comply with her demands.

“I want kunafah, and I want it now!” she shrieked, throwing whatever objects came to hand at her bewildered husband. “Either you buy it for me tonight, or I will make your life so miserable that you will wish you had never been born!”

Ma’aruf, driven to desperation by this ultimatum, made a decision that would transform his entire existence. Rather than endure another night of Fatimah’s rage, he would somehow obtain the money to purchase the kunafah, even if it meant borrowing from neighbors or delaying payment of debts.

He went first to Ahmad the baker, who sometimes extended credit to regular customers. “Brother Ahmad,” he pleaded, “my wife has developed a craving for kunafah, and I lack the funds to purchase it. Could you lend me enough to buy a small portion? I will repay you as soon as possible.”

Ahmad, who was well aware of Fatimah’s reputation in the neighborhood, shook his head sympathetically. “Ma’aruf, my friend, I would help you if I could, but my own circumstances are difficult. Perhaps you could ask Hassan the grocer—he sometimes has extra money from his recent sales.”

But Hassan also declined to provide a loan, as did Muhammad the blacksmith, Ibrahim the tailor, and every other merchant or craftsman in their quarter. Word of Ma’aruf’s desperate quest for kunafah money had spread through the neighborhood, and while everyone sympathized with his plight, no one had sufficient resources to help.

As the evening grew later and Ma’aruf’s situation became more desperate, he made an even more fateful decision. Rather than return home empty-handed to face Fatimah’s wrath, he would leave Cairo entirely and seek his fortune in distant lands where his wife’s voice could not reach him.

With nothing but the clothes on his back and a few copper coins in his pocket, Ma’aruf joined a caravan departing for Alexandria, intending to find passage on a ship bound for any destination that offered the possibility of escape from his matrimonial misery.

The caravan journey proved to be the beginning of Ma’aruf’s transformation from victim to victor. His gentle manner and honest nature impressed the other travelers, and by the time they reached Alexandria, he had been offered a position as assistant to a merchant named Ali al-Shami, who was traveling to the great commercial centers of the Eastern Mediterranean.

“You seem to be a man of good character,” observed Ali al-Shami as they boarded a ship bound for the port of Ikonium. “Your knowledge of leather goods could be valuable in markets where quality craftsmanship is appreciated. If you work faithfully for me, I will ensure that you earn enough to support yourself comfortably.”

The sea voyage opened Ma’aruf’s eyes to possibilities he had never imagined. The ship carried merchants from a dozen different countries, each with stories of fortunes made and lost in the great trading centers of the world. For the first time in his adult life, Ma’aruf began to believe that he might achieve something more than mere survival.

When they reached Ikonium, a prosperous city in the land of the Rum, Ma’aruf’s life changed dramatically once again. Ali al-Shami introduced him to the local merchants as a leather expert from Cairo, and Ma’aruf’s honest manner and genuine knowledge quickly earned him respect and friendship among the trading community.

However, the transformation that would make Ma’aruf legendary began with a misunderstanding that he was initially too embarrassed to correct. When asked about his background by curious merchants, Ma’aruf mentioned that he had been involved in the leather trade in Cairo, which was true enough. But his listeners, impressed by his obvious expertise and dignified bearing, assumed that he had been a wealthy merchant rather than a humble cobbler.

“Ah,” said Mahmud al-Rumi, one of the most successful traders in the city, “so you are one of the great leather merchants of Cairo! I have heard that the finest goods in the world come from your city’s craftsmen. You must have connections with the most skilled artisans and access to the best raw materials.”

Ma’aruf, who had never claimed to be more than he was, found himself caught between honesty and opportunity. If he corrected the misunderstanding, he might lose the respect and friendship he had begun to enjoy. If he allowed it to continue, he might be able to build a new life far from the misery of his marriage to Fatimah.

“Indeed,” he replied carefully, “I have extensive knowledge of the leather trade in Cairo.” This statement was technically true, though it described his knowledge as a craftsman rather than his position as a merchant.

Word of the wealthy Cairo merchant’s arrival spread throughout Ikonium’s commercial district, and Ma’aruf found himself invited to dinners, consulted about market conditions, and treated with a respect he had never experienced before. The merchants of Ikonium, eager to establish profitable relationships with what they believed to be a major trading house, began offering him partnerships and investment opportunities.

Within weeks, Ma’aruf had been established in comfortable quarters, provided with a line of credit by eager local merchants, and invited to participate in trading ventures that promised substantial profits. His honest character and genuine expertise in evaluating leather goods quickly validated the confidence that had been placed in him.

The success that followed was both remarkable and well-deserved. Ma’aruf’s investments, guided by practical knowledge rather than speculation, generated substantial returns. His reputation for fair dealing attracted customers from distant cities, and his workshop became known for producing leather goods of exceptional quality.

As months passed and Ma’aruf’s wealth grew, he began to believe that his transformation from cobbler to merchant was permanent. He sent gifts to the poor of Ikonium, supported charitable causes, and conducted his business with such integrity that even his competitors respected him.

However, Ma’aruf’s greatest challenge lay ahead. The Sultan of Ikonium, hearing reports of this remarkable merchant from Cairo, decided to arrange a marriage between Ma’aruf and his own daughter, Princess Dunya. This princess was renowned throughout the land for her beauty, intelligence, and virtue—everything that Fatimah was not.

“Noble merchant,” declared the Sultan during a formal audience, “your reputation for wisdom and generosity has impressed me greatly. I offer you the hand of my daughter in marriage, along with a dowry that will make you one of the wealthiest men in my domains.”

Ma’aruf found himself in an impossible situation. He could not reveal that he was already married to Fatimah without destroying the entire foundation of his new life. Yet he could not marry the princess while his first wife still lived, for such an action would violate both religious law and his own moral principles.

After much agonizing reflection, Ma’aruf decided to accept the Sultan’s offer while privately determining to find some way to resolve his marital situation honorably. Perhaps Fatimah had remarried during his absence, or perhaps he could arrange for a legal dissolution of their union.

The wedding ceremony was magnificent beyond anything Ma’aruf had ever imagined. He found himself married to a woman whose beauty was matched by her kindness, whose intelligence complemented his own practical wisdom, and whose gentle nature provided a stark contrast to Fatimah’s constant hostility.

Princess Dunya proved to be not only a loving wife but also a valuable partner in his business enterprises. Her knowledge of court politics and commercial regulations helped Ma’aruf avoid pitfalls that might have destroyed less well-connected merchants, while her personal wealth provided capital for even more ambitious trading ventures.

For two years, Ma’aruf lived in happiness that seemed too perfect to be permanent. His business flourished, his marriage brought him joy, and his reputation extended throughout the lands of the Eastern Mediterranean. He had achieved everything that his desperate flight from Cairo had been intended to accomplish.

But Allah, in His wisdom, does not allow injustices to remain unresolved forever. One day, as Ma’aruf conducted business in the port of Ikonium, he encountered a familiar figure among the passengers disembarking from a ship recently arrived from Alexandria—it was Fatimah, apparently having traced his movements across the Mediterranean.

“Ma’aruf, you miserable wretch!” she screamed the moment she spotted him, her voice carrying clearly across the crowded harbor. “Did you think you could escape from your lawful wife by running away to foreign lands? I have spent two years searching for you, and now I have found you living in luxury while I suffered poverty and abandonment!”

The scene that followed was a nightmare of embarrassment and legal complications. Fatimah’s claims to be Ma’aruf’s wife could not be easily dismissed, and the scandal of his apparent bigamy threatened to destroy everything he had built in Ikonium.

Princess Dunya, however, demonstrated the wisdom and compassion that had made Ma’aruf love her. Rather than react with anger or jealousy, she listened carefully to both versions of the story and proposed a solution that honored both justice and mercy.

“Husband,” she said privately to Ma’aruf, “I can see that this woman was indeed your wife in Cairo, and that your marriage to me, while conducted in good faith, creates a legal problem that must be resolved. But I can also see that she treated you with such cruelty that your flight was justified.”

After consulting with religious scholars and legal experts, Princess Dunya arranged for Fatimah to be provided with a substantial financial settlement in exchange for agreeing to a formal divorce. The amount offered was far more than Fatimah could have earned in a lifetime of marriage to a poor cobbler, and it represented genuine compensation for the years of abandonment she had suffered.

Fatimah, faced with the choice between a return to poverty with Ma’aruf or immediate wealth without him, chose the money. The divorce was formalized according to religious law, and Ma’aruf’s marriage to Princess Dunya was validated by the religious authorities.

But the most remarkable aspect of this resolution was Ma’aruf’s own transformation. The wealth and success he had achieved had not corrupted his essential character—he remained the same honest, compassionate man who had endured years of abuse with patient resignation. His experience of prosperity had taught him the value of generosity and justice, rather than leading him to selfishness and pride.

In the years that followed, Ma’aruf became one of the most respected figures in Ikonium and throughout the lands of the Eastern Mediterranean. His business enterprises provided employment for hundreds of workers, his charitable foundations supported the poor and orphaned, and his example inspired other merchants to conduct their affairs with integrity and compassion.

When Ma’aruf and Princess Dunya were blessed with children, they raised them to understand that true nobility comes not from birth or wealth but from character and conduct. The children grew up hearing the story of their father’s transformation from cobbler to merchant, learning that divine providence rewards patience and virtue while ensuring that cruelty and injustice eventually receive their proper consequences.

The tale of Ma’aruf the Cobbler became one of the most popular stories told in the coffee houses and markets of the Islamic world. Some listeners were inspired by the possibility of dramatic transformation in their own lives, while others found comfort in the demonstration that even the most oppressive circumstances could eventually be overcome.

Scholars and theologians used Ma’aruf’s story to illustrate various moral principles—the importance of enduring hardship with patience, the value of maintaining one’s integrity under pressure, and the way divine justice operates through seemingly random events to reward virtue and punish vice.

In his old age, when Ma’aruf had become a patriarch whose opinions were sought by rulers and merchants throughout the region, he would often reflect on the strange sequence of events that had transformed his life. A craving for kunafah had led to his flight from Cairo, which had led to his meeting with Ali al-Shami, which had led to his misidentification as a wealthy merchant, which had led to his actual prosperity and eventual happiness.

“Children,” he would tell his grandchildren as they gathered around him in the garden of his magnificent palace, “never underestimate the power of Allah to transform even the most desperate circumstances into blessings. What seems like disaster may be the beginning of salvation, and what appears to be an ending may actually be a new beginning.”

He would often add, with the wisdom that comes from experiencing both poverty and wealth: “But remember also that prosperity is a test as surely as adversity is. It is easier to be good when you are poor and powerless than when you are rich and influential. True success is measured not by what you achieve but by who you become in the process of achieving it.”

Thus ends the tale of Ma’aruf the Cobbler, whose extraordinary journey reminds us that divine providence works through the most ordinary events to accomplish extraordinary transformations, that patience in suffering prepares the soul for wisdom in prosperity, and that the humblest beginnings can lead to the most remarkable conclusions when character remains constant through all the vicissitudes of fortune.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus