The Origin of Palm Wine

Original Nsafufuo Mfiase

Story by: Traditional — retold by Tell Story

Source: Akan Oral Tradition

Come close, and hear the story of the tree that gives the sweet cup. The old tellers say this tale when palms are heavy and hands are sticky with harvest. It is a song about patience and the quiet work of people who listen to the land.

There was a time, before the drums knew the measures we clap today, when the people drank only the river’s water and the milk of the land. In a small grove of tall palm trees, there lived a young man named Kweku, who loved the sound of laughter more than his own reflection. Kweku had a brother, and they worked the fields, yet he always watched the traders leave with jars of far-off spices and wine, dreaming of a drink that would make celebrations sing.

One afternoon, as the sun leaned west and painted the palms golden, an old woman arrived at the village. Her hair smelled of smoke and she carried a small gourd carved with patterns. “I have tasted moons,” she said, “and I know the places where the trees speak.” The villagers gathered, and Kweku’s ears pricked like a listening goat.

The old woman told of a secret: if a man listened to the palm and coaxed it with song and patience, the tree would offer a sweet sap. “But heed this,” she warned; “the sap will give only to hands that give back. Take without care, and the tree will close its mouth.”

Kweku could not sleep that night for thinking of the sap. He rose before the roosters and walked among the palms, touching their trunks. He sang to them the songs his grandmother hummed while pounding cassava. He set small offerings — a pinch of millet, a smear of palm oil — into the crooks where the fronds met the trunk. Days turned to weeks, and Kweku’s patience wore at his edges like river stones.

Then, one dawn, the palm trembled. A sweet drop collected in a leaf and fell into a waiting gourd. Kweku’s heart beat like the mender’s drum. He tasted the sap; it was bright and clean and carried the smell of rain. Word flew: Kweku had found the palm’s treasure.

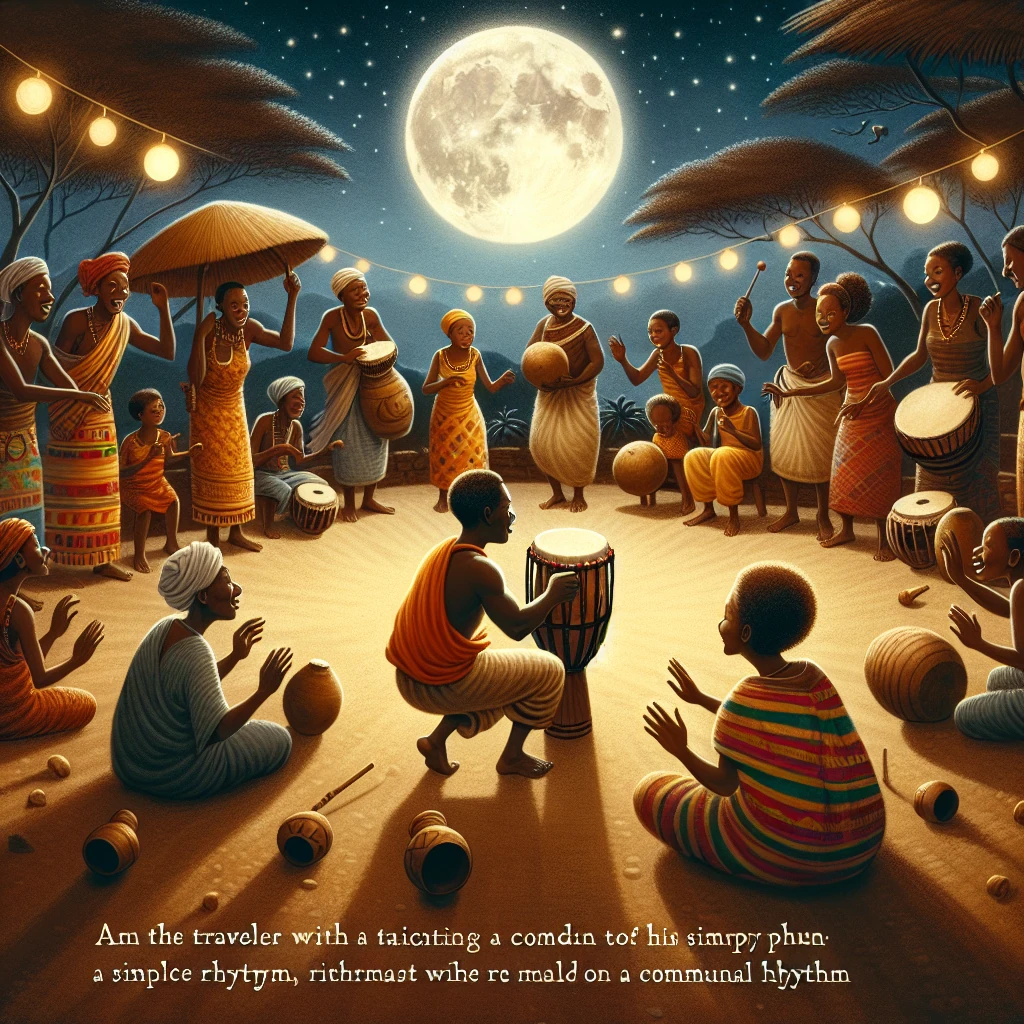

He shared the first cups with his neighbours. The elders tasted and smiled, and a hush like the space between drumbeats spread through the grove. The people learned to tap the palm with respect — a small notch, a gourd hung with care, and a song to the tree. Festivals changed; gatherings had a new sweetness that loosened old grievances. The youth danced differently and old lovers held hands with softer patience.

But there was always one whose eyes sharpened at new gifts. A trader from the town, whose belly longed for coin more than company, saw the new drink and thought only of bottles and sale. He went to the grove and spoke in a smooth voice: “Teach me how to make it for the market, and I will buy your jars at good price.” Greed crept in like a vine.

The people were tempted. They imagined jars lined up on the road, money woven into sacks. Yet the old woman said, “If you ask the tree to give without care, it will dry its mouth. Treat it like a friend, and it will remain a friend. Take with greed, and it will forget your name.” But the trader whispered again, and some followed him to the market to learn the notch and the hollow — only they did not sing, only they took.

Soon, the palms in the far fields that were used for quick gain grew thin and silent. The sap tasted bitter where the notch had been deep and careless. Children saw their fathers return from the market with jars but with less joy at home. The village knew a sorrow that counted like lost days.

Kweku and his brother gathered the people beneath the oldest palm. The elders told a story of balance and gave the traders a choice: honor the palms with patience and share the craft, or leave the grove. Those who chose haste saw their jars empty faster than the sun’s warmth.

Years braided themselves into tradition. The people made a law: each family received a season to tend one tree, and they would share its sap with the compound. The palm became part of the family — its naming and tending a ceremony. Young ones learned the songs and the right way to make a notch that would not harm the tree.

From then on, palm wine — the sweet sap — was more than a drink. It was the memory of patience and community stitched into clay cups. It was poured at weddings, at funerals, and when a child took its first step. The song of the palm is still sung by the elders when the sky is clear.

So, my children, remember: gifts of the earth are generous when we are gentle. Take care, tend with song, and the palms will answer with sweetness. The elders say, “Woara na yɛ adwuma — treat the thing with your hands, and it will treat you back.” Pour well, and share wide.

— End —

Comments

comments powered by Disqus