The Origin of Cowries

Original Sedie Mfiase

Story by: Traditional Akan Folklore

Source: Akan Oral Tradition

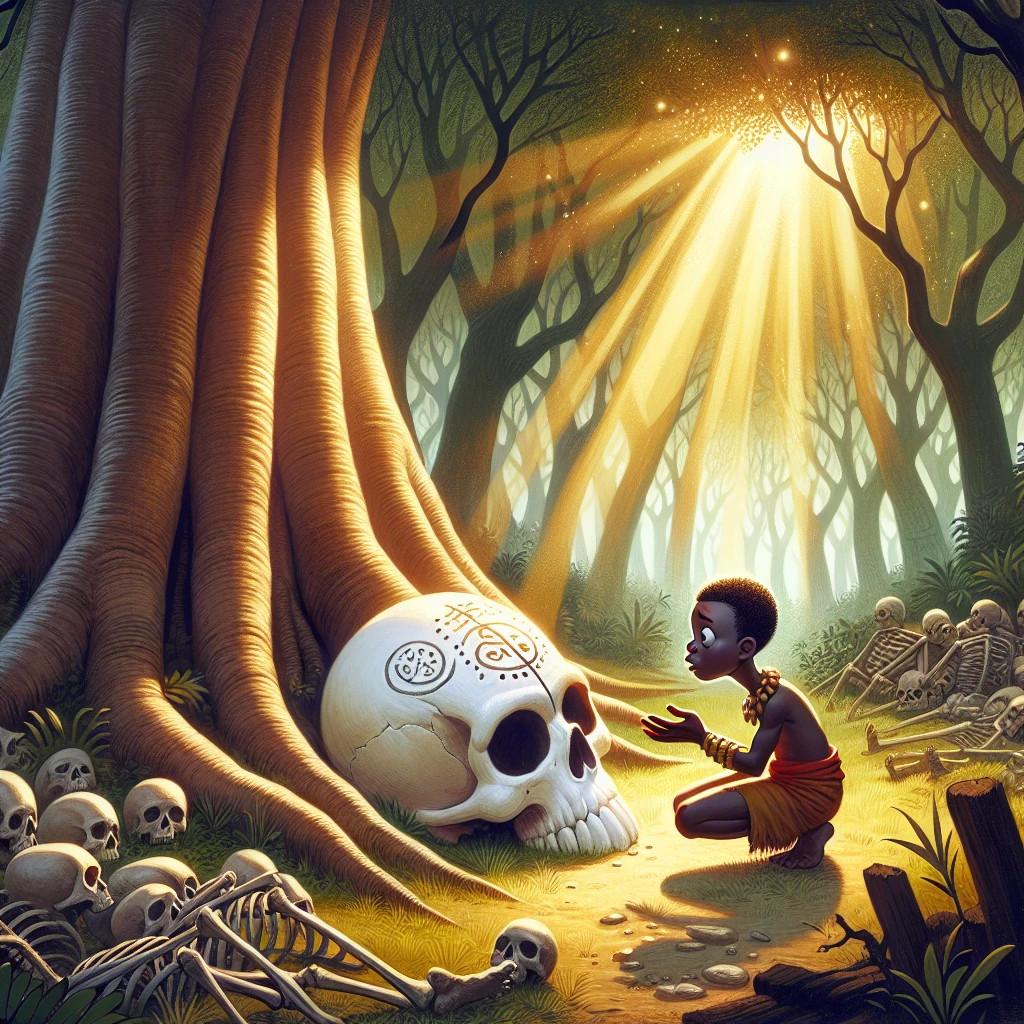

Come close, children, and hear the tale of how the beautiful cowrie shells came to be the first money of our people, a gift from the ocean goddess herself.

The Trading Village

Long ago, when the world was younger and the paths between villages were first being worn by the feet of traders, there lived a coastal community whose people had developed a great skill for making beautiful crafts and growing abundant crops. The village of Anomabo sat where the great forest met the endless blue waters, and its people had learned to harvest the wealth of both land and sea.

The villagers were talented artisans who could weave cloth that shimmered like sunlight on water, carve wood into sculptures that seemed to breathe with life, and forge iron into tools and weapons that were renowned throughout the region. Their farmers could coax abundant harvests from the rich soil, and their fishermen brought in catches that filled the village with the sweet smell of the sea’s bounty.

But despite their prosperity and skill, the people of Anomabo faced a problem that grew larger as their reputation spread and more traders came to seek their goods. They had no reliable way to measure and exchange value in their transactions with visitors from distant lands.

When traders from the northern kingdoms came seeking their beautiful cloth, they would offer ivory, gold dust, or exotic animals in return. When visitors from the eastern regions arrived wanting their iron tools, they might propose to trade salt, dried meat, or rare stones. Each transaction required lengthy negotiations to determine fair exchange rates, and disagreements often arose about the relative value of different goods.

The Merchant’s Dilemma

Among the village’s most successful traders was a man named Kwaku who had built his reputation through fair dealing and exceptional skill at evaluating the worth of different goods. Kwaku could assess the quality of gold dust with a glance, determine the age and condition of ivory by its color and weight, and judge the value of exotic goods from distant regions based on their rarity and craftsmanship.

But even Kwaku struggled with the complexity of barter transactions, especially when dealing with traders who spoke different languages and came from cultures with very different ideas about what constituted valuable goods.

“How can we establish fair prices,” Kwaku would ask his fellow merchants, “when every transaction requires us to compare things that cannot truly be compared? How do we weigh the value of a fine cloth against a piece of ivory, or judge whether a bag of salt is worth more or less than a carved mask?”

The problem became more acute as trade relationships expanded and transactions became more complex. Sometimes traders would want to purchase multiple different items, or they would arrive with goods that were difficult to evaluate, or they would propose multi-party exchanges involving several different merchants.

The Ocean’s Call

One morning, as Kwaku walked along the beach pondering these trading difficulties, he noticed something unusual about the rhythm of the waves. Instead of their normal, random pattern, the waters seemed to be moving in a deliberate, almost musical sequence that reminded him of the ceremonial drumming performed during important village celebrations.

As he stood listening to this strange oceanic rhythm, Kwaku began to feel drawn toward the water. The pull was gentle but persistent, like the feeling of being called by a beloved friend. Without fully understanding why, he found himself wading into the surf, walking deeper and deeper until the waves reached his chest.

Suddenly, the water around him began to glow with a soft, pearl-like radiance, and Kwaku realized he was no longer alone in the ocean. Rising from the depths came a figure of extraordinary beauty—a woman whose skin shimmered with the colors of sea foam, whose hair flowed like underwater plants, and whose eyes held the deep wisdom of the ocean’s mysteries.

“Greetings, Kwaku of Anomabo,” the ocean goddess said in a voice that sounded like the gentle lapping of waves on sand. “I have been watching your people and observing the challenges they face in their trading relationships.”

The Goddess’s Wisdom

As Kwaku stood in amazed silence, the ocean goddess continued speaking. “Your village has become a place where people from many different regions come to trade, bringing with them goods from across the known world. But the lack of a common medium of exchange creates conflict and confusion that diminishes the joy and mutual benefit that trade should provide.”

“You are correct, great goddess,” Kwaku managed to reply. “We struggle daily with the problem of determining fair exchanges between goods that have no obvious relationship to each other. Many potentially beneficial trades are never completed because the parties cannot agree on relative values.”

The ocean goddess nodded thoughtfully. “The solution to your problem lies not in finding better ways to compare different goods, but in establishing a single item that all traders can agree represents value itself. What you need is something that can serve as a common measure for all exchanges.”

“But what item could serve such a purpose?” Kwaku asked. “It would need to be something that everyone values, that cannot be easily counterfeited, that is durable enough to last through many exchanges, and that exists in sufficient quantities to serve the needs of many traders.”

The Divine Gift

In response to Kwaku’s question, the ocean goddess reached into the depths and brought forth a handful of small, white shells that seemed to glow with inner light. Each shell was perfectly formed, smooth and beautiful, with a distinctive shape that was immediately recognizable.

“These are cowrie shells,” the goddess explained, “and they will serve as the first currency for your people and all who trade with them. Each shell is a gift from the ocean itself, created in the depths where no human can go, shaped by the patient work of sea creatures over many seasons.”

As she spoke, the goddess demonstrated the shells’ special properties. “Observe how each cowrie has the same basic size and weight, making them easy to count and measure. Notice how their hard surface resists damage and their distinctive shape makes them impossible to counterfeit convincingly. See how their natural beauty makes them desirable to people from all cultures and regions.”

Kwaku examined the shells with growing amazement. They were indeed perfectly suited to serve as currency. Their uniform size made them easy to count, their durability meant they could be used repeatedly without deteriorating, and their beauty gave them inherent value that people would be willing to accept.

The System of Value

“But how will people know how many cowries different goods are worth?” Kwaku asked. “How will we establish the exchange rates between cowries and other items?”

The ocean goddess smiled. “That knowledge will develop naturally through use and experience. Begin by establishing the value of cowries relative to goods your village produces. Decide, for example, that a fine cloth is worth one hundred cowries, or that a well-made iron tool is worth fifty.”

“As traders from other regions begin using cowries,” she continued, “they will establish their own exchange rates based on what the shells can purchase in your market. Gradually, a network of agreed-upon values will spread across all the trading regions, creating a common system that benefits everyone.”

The goddess then showed Kwaku how the cowrie system would work in practice. “Instead of trying to negotiate whether a piece of ivory is worth two cloths or three, traders will simply determine how many cowries each item is worth. The ivory might be valued at two hundred cowries, and the cloth at one hundred, making the exchange ratio clear and unambiguous.”

The Spreading Abundance

As the ocean goddess prepared to return to the depths, she made one final gesture that would ensure the success of the cowrie currency system. She scattered the glowing shells across the waters, and immediately, countless cowries began washing up on the beaches all along the coast.

“These shells will continue to appear on your shores,” she told Kwaku, “in quantities sufficient to meet the needs of expanding trade, but not so many as to make them worthless through excessive abundance. The ocean will provide what is needed, when it is needed.”

The goddess also explained that cowries would be found on other coastal regions as well, ensuring that the currency system could spread naturally as traders carried the shells to distant markets and introduced them to new trading partners.

As she sank back into the glowing waters, the ocean goddess left Kwaku with a final piece of wisdom: “Remember that money is a tool for facilitating cooperation and mutual benefit among people. Use these cowries to build relationships, not to create inequality or exploitation.”

The Transformation of Trade

When Kwaku returned to the village with his handful of magical cowrie shells and told the story of his encounter with the ocean goddess, the people of Anomabo were initially skeptical. The idea of using small shells as money seemed strange and impractical to those accustomed to bartering with substantial goods like cloth, tools, and food.

But as Kwaku demonstrated how the cowrie system could simplify their trading relationships, the villagers quickly began to see its advantages. Within days, they had established cowrie values for all their major products and were using the shells to conduct transactions among themselves.

When the next group of traveling traders arrived, the merchants of Anomabo introduced them to the cowrie currency system. The visitors were intrigued by the concept and quickly appreciated how much easier it made their negotiations. Instead of spending hours trying to compare the relative values of disparate goods, they could quickly establish prices in cowries and complete their transactions efficiently.

The Expanding Network

As traders who had learned to use cowries traveled to other markets, they introduced the system to new regions. The shells’ beauty and obvious utility as a medium of exchange made them readily accepted by people who had never heard of the ocean goddess or the village of Anomabo.

The cowrie currency system spread organically along the established trade routes, carried by merchants who found it far superior to the complex barter arrangements they had previously used. Villages that adopted the system experienced immediate improvements in their trading relationships, as negotiations became simpler and disputes over fair exchange became less common.

Within a few years, cowries had become the standard currency across a vast network of trading communities. The shells were valued not only for their utility as money but also for their beauty, and people began using them for decoration and ceremonial purposes as well as trade.

The Wisdom of the System

As the cowrie currency system matured, the people of the region discovered that the ocean goddess had been wiser than they initially realized. The shells proved to be nearly perfect money for their time and culture, with properties that addressed all the major challenges of their trading relationships.

The cowries’ durability meant they could be used repeatedly without deteriorating, their distinctive appearance made them difficult to counterfeit, and their natural scarcity gave them inherent value that was recognized across cultural boundaries. Most importantly, their use as currency encouraged trade and cooperation rather than conflict and exploitation.

The ocean goddess’s prediction about the natural development of exchange rates also proved accurate. As the cowrie system spread, a stable network of agreed-upon values emerged organically, creating a common economic language that facilitated trade across vast distances and cultural differences.

The Cultural Impact

The introduction of cowrie currency had effects that went far beyond simplifying trade transactions. The system enabled the development of more complex economic relationships, including credit arrangements, savings practices, and investment in long-term projects.

Villages could now accumulate wealth in a stable form that didn’t spoil or deteriorate, allowing them to plan for future needs and invest in improvements to their communities. Individuals could save cowries to purchase goods that would have been beyond their reach under the barter system, and craftspeople could specialize in their particular skills without worrying about finding direct exchanges for their products.

The cowrie system also facilitated the development of market towns and trading centers, as merchants could now establish permanent shops and warehouses without needing to negotiate individual barter arrangements with every customer.

The Lasting Legacy

For generations, cowrie shells remained the primary currency across much of West Africa, facilitating trade relationships that spanned vast distances and connected diverse cultures. The shells were valued not only as money but as symbols of prosperity, fertility, and divine blessing.

The cowrie currency system demonstrated the wisdom of the ocean goddess’s gift and the importance of having reliable mediums of exchange for economic development. Even as other forms of money eventually supplemented and replaced cowries, the shells continued to hold cultural significance as reminders of the divine origins of prosperity and trade.

The story of the cowries’ origin became a teaching tale about the proper relationship between money and community well-being, emphasizing that currency should serve to bring people together rather than divide them.

The Eternal Teaching

Today, when Akan storytellers share the tale of the origin of cowries, they emphasize that money is a tool given by divine wisdom to facilitate cooperation and mutual benefit among people. The story teaches that currency should serve the community rather than creating inequality or exploitation.

The tale reminds us that true prosperity comes not from hoarding wealth but from using resources wisely to build relationships and create opportunities for everyone to flourish.

Most importantly, the story shows that the greatest gifts often come from understanding what serves the common good rather than just individual advantage. The ocean goddess gave the cowries not to make any one person rich, but to create a system that would benefit all who participated in it.

So remember, children: money is like the ocean’s gift of cowrie shells—it should flow like water, bringing life and prosperity wherever it goes. When we use our resources to help others and build our communities, we honor the wisdom of the ocean goddess and ensure that abundance continues to bless all who share in it.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus