How Music Came to the Akan

Original Nnwom Ba Akanman Mu

Story by: Traditional — retold by Tell Story

Source: Akan Oral Tradition

Before there were songs to call the farmers, before the drumbeat taught the feet to move, the land was a quiet place of harvest and hush. People spoke softly and kept rhythm in the beating of their own hearts.

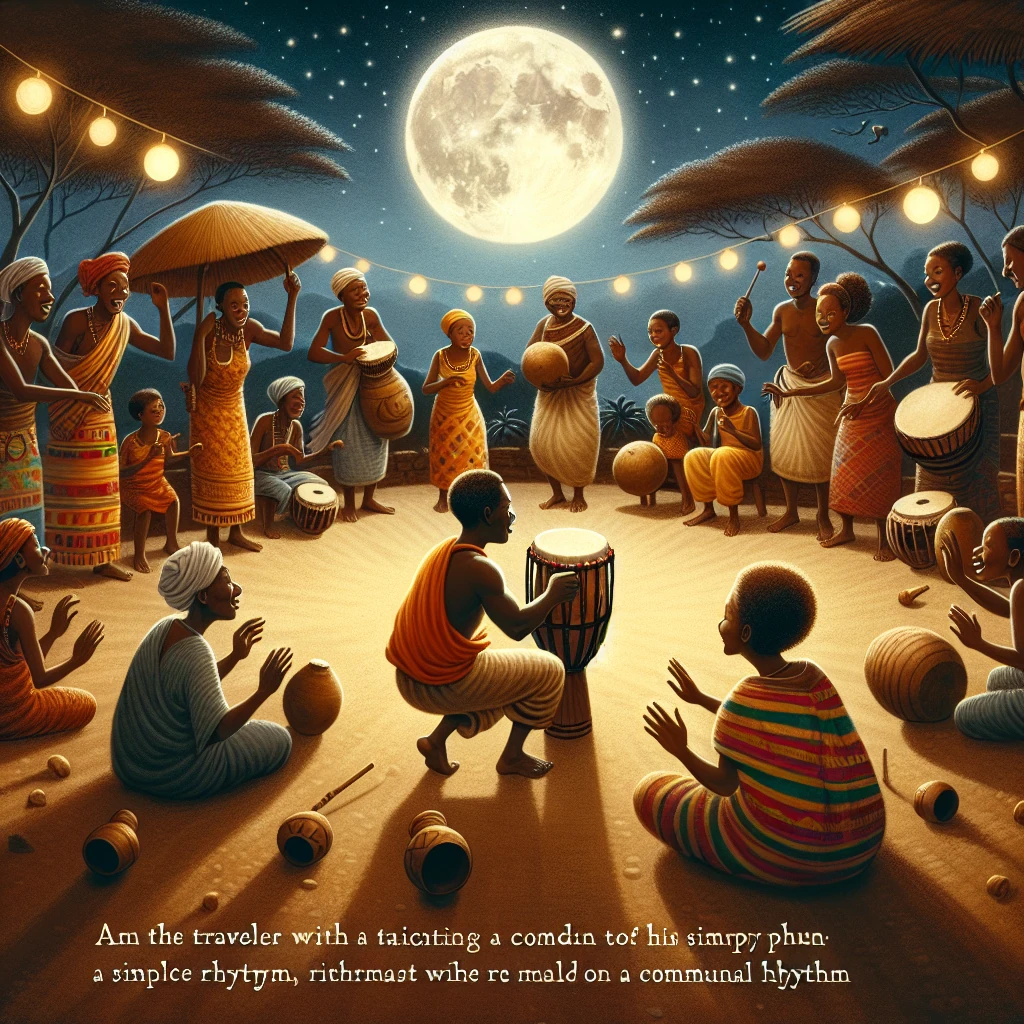

It was said that music was born when a traveller came to the village carrying a small carved drum. His hands were callused and his mouth remembered many roads. He taught the children one beat, then two, and the people found themselves moving in ways they’d never tried. The elders called this a weaving of sound — a thread that could stitch strangers to friends.

The first rhythm was simple: a low thump like stepping into cool water, a sharp clap like the snap of a twig. The women sang a line that smelled of cassava and morning; the men answered with a hum that smelled like the earth. Even the sky seemed to listen, and the moon leaned low to hear.

As the rhythm grew, each family brought something to the music: the pot’s rim became a bell, a hoe’s metal became a tinny note, and a child’s rattle added shimmer. The traveller said, “Music is the language of the hands and the heart. Keep it simple; keep it shared.” The people learned songs for planting, songs for mourning, and songs for love.

But the traveller also warned: music asked for discipline and care. If a person played only for praise, the music would grow hollow. A young man named Kojo sought praise and learned only empty rhythms that echoed his ego. The elders taught him a song of work, and when he learned it, the rhythm found him again, humble and true.

Thus music became lawless neither — it was tool and prayer. Drums were carved carefully, skins tended, and songs remembered. When children danced, the elders taught them the stories hidden in each beat, so that a person who could hold rhythm also held memory.

From then on, music was in the soil and on the breath. It called fish to nets, cheered mothers in labour, and remembered the names of those who passed. The people say that if you listen at dusk you can still hear the traveller’s first drum under the wind’s hum.

So when the drum sounds and your feet step, know that you are walking on the same path as the first hands that learned to make sound. The elders say, “Nnwom yɛ nkɔmɔ — song is conversation.” Keep the rhythm, and the community will keep you.

— End —

Comments

comments powered by Disqus